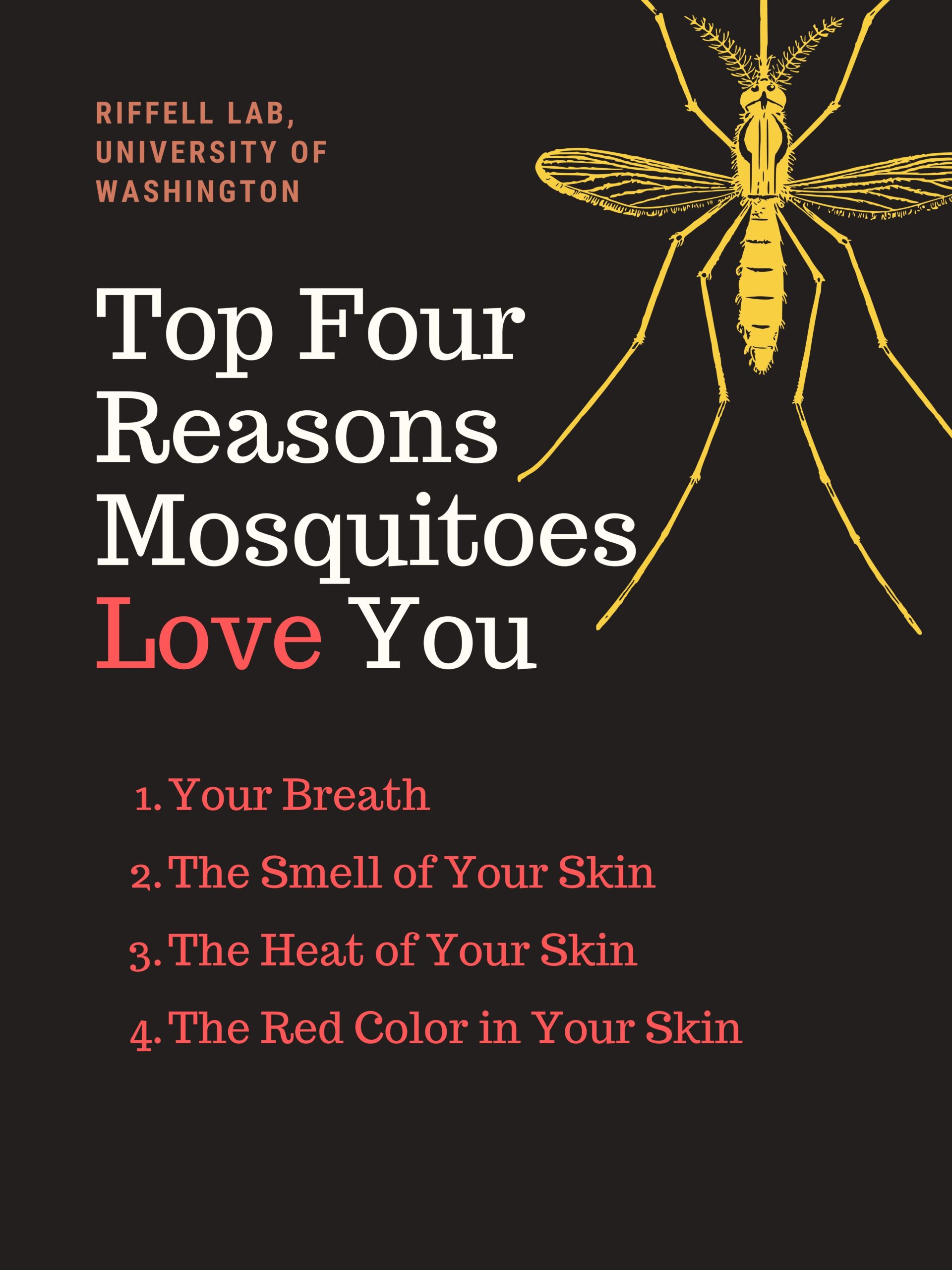

Mosquitoes see red, which may be why they find us so appealing

These insects prefer certain hues — especially skin tones

New research shows that Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, such as this one, are attracted to specific colors, especially red.

Kiley Riffell

By Laura Allen

Bzzz. Oh no — a mosquito. Have you ever wondered how these small insects are so good at finding you? A new study has just identified one way they home in on us. It’s visual. Mosquitoes just like the look of our skin.

Claire Rusch studies these bloodsuckers at the University of Washington in Seattle. She and her colleagues have been working to uncover ways to avoid mosquito bites. And this biologist knows plenty about that. After all, to study mosquitoes, “you get bitten a lot,” she notes. “It’s not easy to work with an animal that preys on you.”

A bite from the mosquito that carries yellow fever can be more than annoying, though. The Aedes aegypti mosquitoes that Rusch studies can transmit the viruses that cause dengue, yellow fever and Zika. These diseases sicken hundreds of millions of people each year. Many of those people die.

But Rusch and her team just discovered something that could help ward off disease-carrying mosquitoes. A. aegypti mosquitoes are attracted to a select few colors, and especially ones with long wavelengths of light. We see these hues — the same wavelengths given off by human skin — as red. That intel could lead to the design of better traps to lure mosquitoes away from people.

Rusch’s group described its new findings February 4 in Nature Communications.

It’s hard to hide from a mosquito

Anyone stuck in a room with a mosquito knows they excel at finding you. These insects can detect the carbon dioxide, or CO2, exhaled in our breath. They also are attracted to sweat, body warmth and contrasting colors. But until now, scientists didn’t know that mosquitoes could detect specific colors.

Some earlier studies had found no clear color preference among mosquitoes. One study found they prefer blue, another that they prefer yellow-green. What should people make of such conflicting results?

Testing a mosquito’s color preference is not simple, it turns out. The apparent color of an object doesn’t just depend on the wavelengths of light it gives off, Rusch explains. It also can be affected by the brightness of that light and its contrast against surrounding colors. Humans see an object’s color largely in terms of the wavelengths of light it gives off. But other creatures’ eyes may be more sensitive to contrast or brightness. “We needed to control for all of those variables to really be sure [a mosquito’s] preferences came from the wavelength of the object,” Rusch says.

To do that, she got help from a University of Washington colleague, Diego Alonso San Alberto. This software engineer designed a test chamber that was 450 mosquito-body-lengths long. Lined with cameras, it recorded the insects’ flight patterns. Two small colored disks laid on the floor of the chamber.

Since the researchers wanted to know if mosquitoes were attracted to certain colors, the disks couldn’t be the darkest or brightest objects in the chamber. Otherwise, it would be unclear if the mosquitoes were attracted to the disks’ color, contrast or brightness. So, the researchers projected a checkerboard pattern onto the floor of the chamber and gray along the walls. That way, if the mosquitoes went to the colored disks, it could only be due to the disks’ color.

The researchers released about 50 starved Aedes aegypti mosquitoes into the chamber at a time. Mosquitoes don’t start hunting until they’ve caught a whiff of carbon dioxide. So, the team sprayed CO2 inside the chamber as part of the experiment. Cameras recorded where the mosquitoes flew, Alonso San Alberto notes, “and how they interacted with the colored disks.” Whichever disk the mosquitoes hovered around longer would be the color the insects preferred.

A surprising find

A whopping 1.3 million mosquito flights later, the team had its results. Before CO2 was sprayed in the chamber, the mosquitoes ignored all the colored disks. With CO2, mosquitoes ignored any disk that was green, blue or purple. But the insects did fly toward disks that were red, orange or cyan (light blue). These colors, apparently, were very enticing. The mosquitoes seemed to especially like red.

That surprised other scientists. One is Iliano Coutinho-Abreu. He’s a biologist at the University of California San Diego who studies mosquitoes. Scientists long thought that mosquitoes relied mostly on body odors and heat to find humans, he says. Now, he concludes, researchers know that vision also plays an important role.

To further investigate that, Rusch’s team placed disks with different skin tones inside their test chamber. But the bloodsuckers didn’t seem to prefer any particular skin colors. All were equally attractive.

The team tested three other mosquito species that feed on people. Red hues attracted each of them, too. But these mosquitoes differed in what other colors they seemed to prefer.

“I found these results surprising and very interesting,” says Trevor Sorrells at Rockefeller University in New York City. As a mosquito neuroscientist, Sorrells studies the brain and the nervous system of these insects. The new research shows mosquitoes can see red light and tell that it is different from other colors. “This is important,” he notes, “because all human skin tones reflect red light better than other colors. So mosquitoes can use it to locate a patch of skin.”

There still is much to learn about how these bloodsuckers see and navigate their world. It seems logical that mosquitoes might be attracted to reds since that is the color human skin appears to them. Still unknown is why are they also attracted to a light blue. And, importantly, how might these new data on color preferences be used to design better mosquito traps or repellents?

Next time you’re out where mosquitoes might lurk, don’t forget the bug spray. And that red shirt? You might want to leave it at home.