average: (in science) A term for the arithmetic mean, which is the sum of a group of numbers that is then divided by the size of the group.

biologist: A scientist involved in the study of living things.

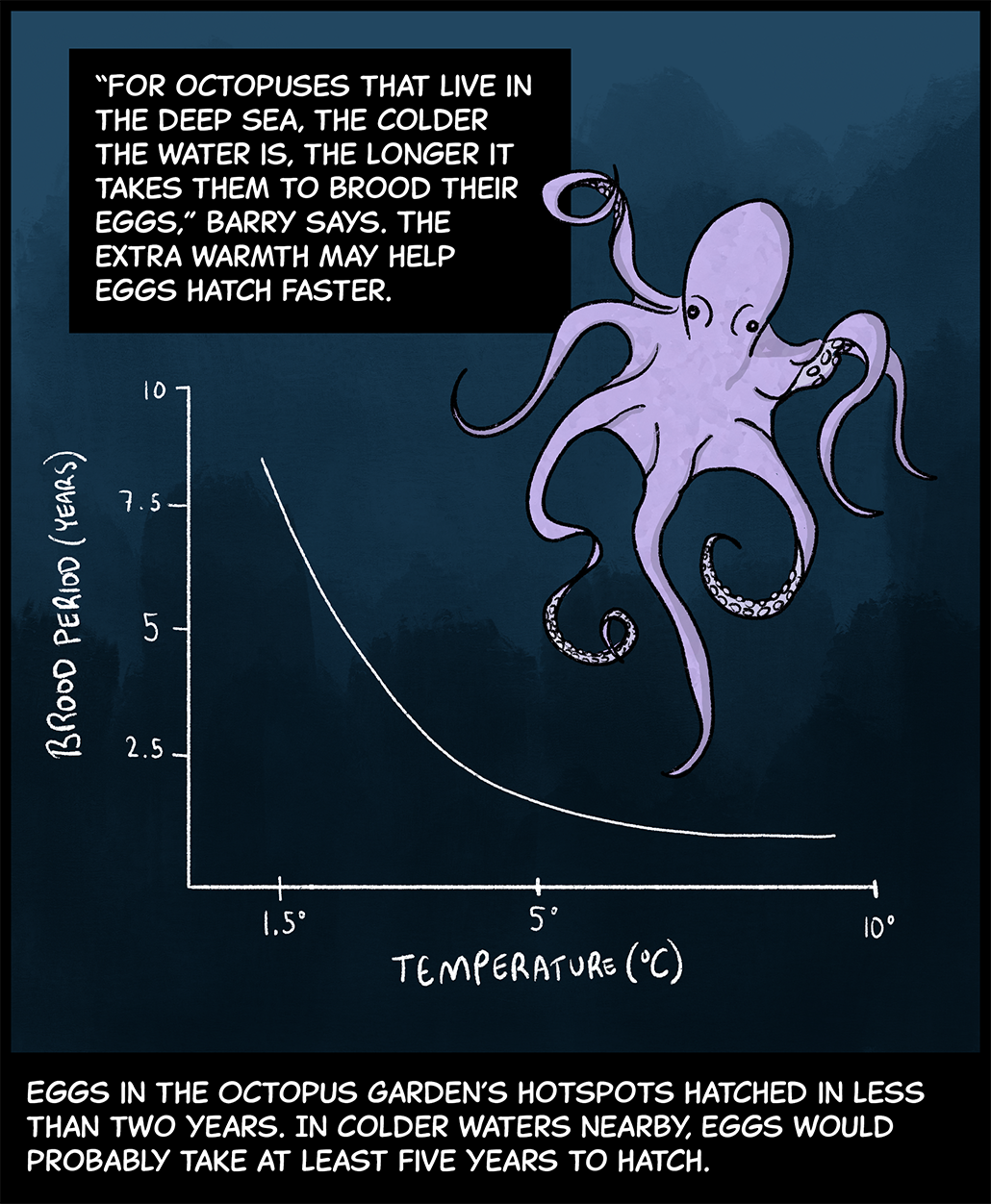

brood: A group of related animals that emerges in a specific region in the same year. Depending on the animal type, the collective group is sometimes also known as a year class. (verb) The act of guarding and/or incubating eggs.

egg: A reproductive cell that contains half of the genetic information necessary to form a complete organism. In humans and in many other animals, ovaries produce eggs. When an egg fuses with a sperm, they combine to produce a new cell, called a zygote. This is the first step in the development of a new organism."

marine biologist: A scientist who studies creatures that live in ocean water, from bacteria and shellfish to kelp and whales.

octopus: (pl. octopi or octopuses) Sea mollusks with a soft, sac-shaped body and eight arms. Two rows of suckers along each arm give the animal an ability to grasp and hold onto things. Cousins of the squids, these animals have a sharp beak-like mouth and good vision.

robot: A machine that can sense its environment, process information and respond with specific actions. Some robots can act without any human input, while others are guided by a human.

sea: An ocean (or region that is part of an ocean). Unlike lakes and streams, seawater — or ocean water — is salty.

sea stars: Another name for starfish, these animals are not true fish. They are related to sand dollars, sea urchins and sea cucumbers.

taste: One of the basic properties the body uses to sense its environment, especially foods, using receptors (taste buds) on the tongue (and some other organs).

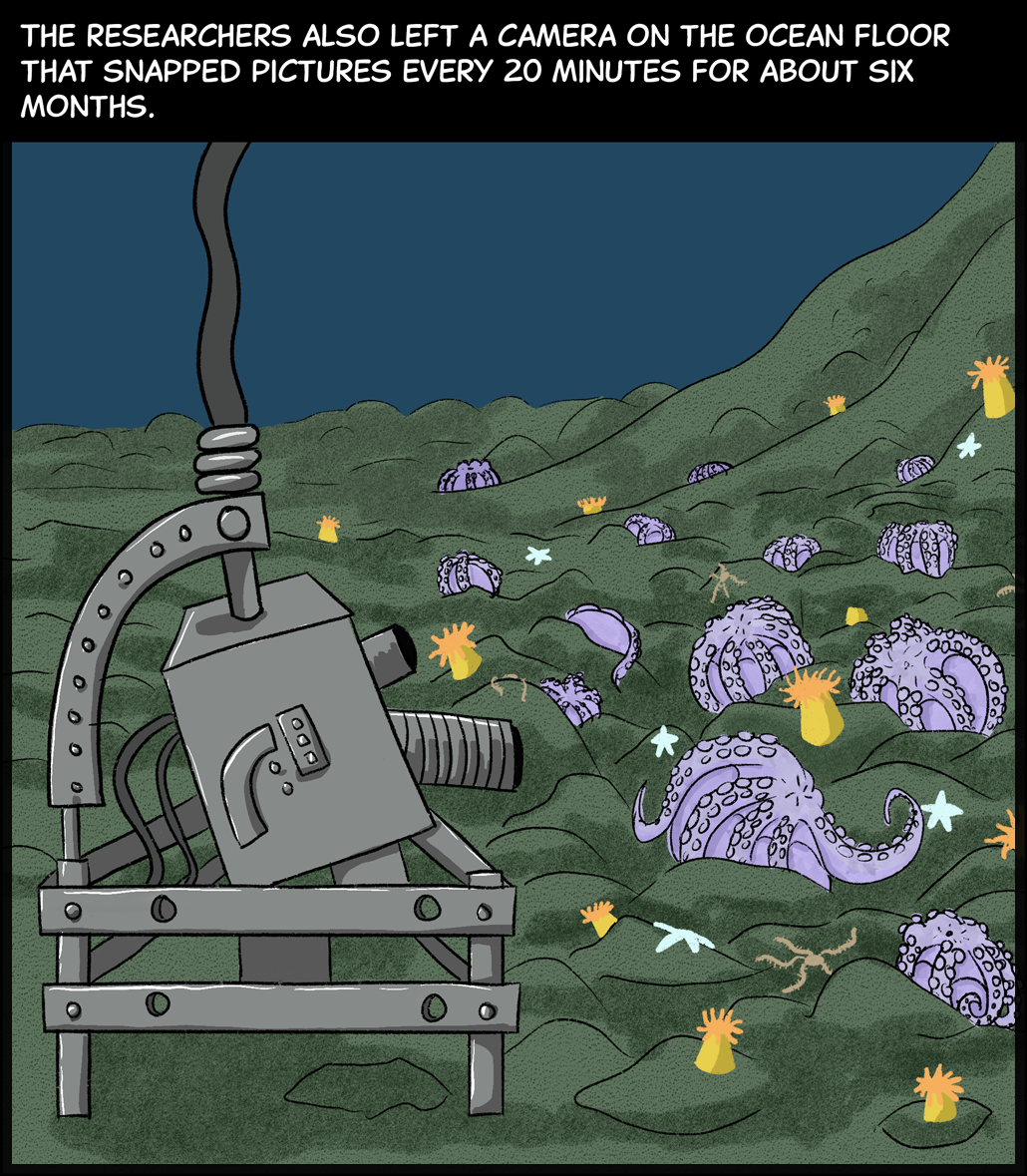

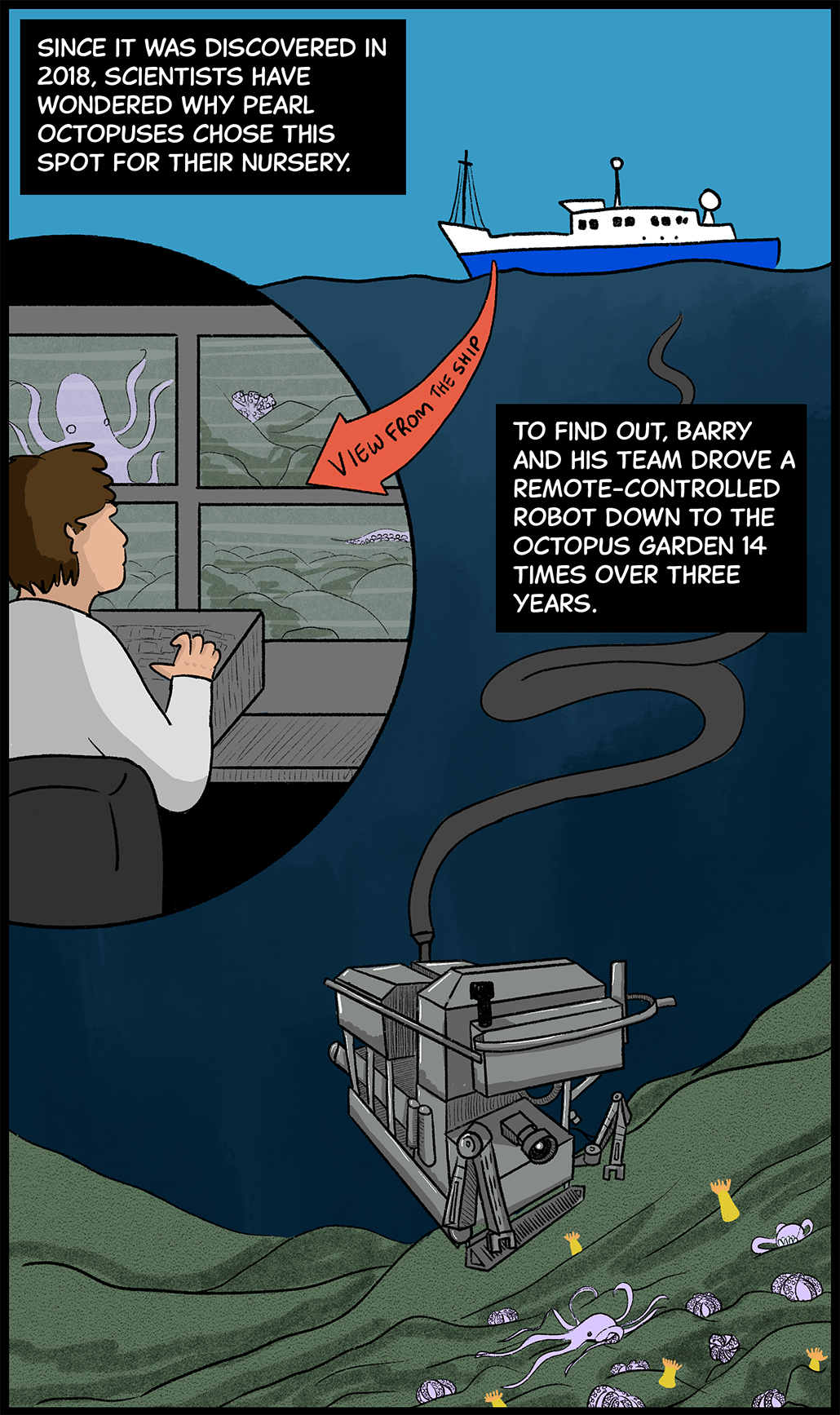

tripod: A three-legged stand for supporting a camera or other device.

![Text (above first image): “You can drive [the robot] right up to them,” Barry says. “We hold cameras literally eight inches away. … They just don’t seem to care.” First image: A camera hovers inches away from a pearl octopus sitting on the seafloor with its arms folded up around its body. Text (above second image): The robot stuck probes in and around octopus nests to measure temperature and other water conditions. Mama octopuses didn’t like that, Barry says. “They just are tenaciously holding on and covering those eggs.” Second image: a gray, cylindrical probe pokes into the cluster of eggs tucked against a mother octopus’s side on the seafloor.](https://www.snexplores.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/1030_WT_Octopus_Garden_Panel_4.png)