Why some people think they know more than vaccine experts

Those who cling to myths often don’t realize what they don’t know, study finds

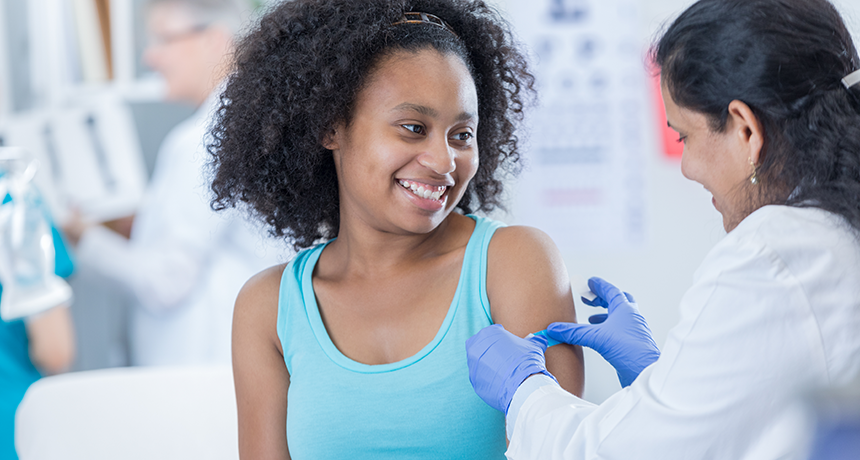

This teen has a reason to smile after getting a vaccine. Vaccines provide long-lasting protection against dangerous diseases.

SDI Productions/E+/Getty Images

Vaccines save lives — millions every year. Yet some parents won’t let their children get this common treatment. New research suggests many of these people think they know more than the experts. That may make them more likely to fall for baseless myths, the study concludes

Matthew Motta is a political scientist at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He studies science communication and the public-policy impacts of people rejecting science. Recently, he and others surveyed 1,310 U.S. adults on their knowledge of autism. Some websites wrongly appeal to parents’ fears that childhood vaccines may cause the complex brain condition — even though study after study has shown that there is no link. Motta’s group also asked how these people felt about government requirements that all children get vaccines.

More than a third of the people surveyed claimed they knew as much or more about the causes of autism than either doctors or scientists. In fact, the opposite was true. People who thought they knew more than the experts generally knew the least about autism. That overconfidence was also strongest among people who oppose vaccines.

The Dunning-Kruger effect helps explain the results, Motta says. Psychologists Justin Kruger and David Dunning first described the effect in 1999. At the time, both worked at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y.

“Some people have so little knowledge about a subject that they actually don’t know how much knowledge they lack,” Motta explains. In other words, people who don’t know what they don’t know can mistakenly think they know plenty. They’re wrong. Yet they feel quite confident that they know more than people who have spent their lives doing research in that field.

Motta’s group also had another finding. Overconfident people are more likely to think that actors or talk show hosts should influence public policy on vaccines. In fact, such celebrities have no expert training and or knowledge. Often they, too, are overconfident — and wrong.

The study appeared in the August 2018 issue of Social Science & Medicine.

Salil Benegal is a political scientist at DePauw University in Greenfield, Ind. He wrote a commentary on the study’s findings. It ran in the September 2018 issue of Social Science & Medicine. The new study, he says, helps explain how overconfidence can “amplify the effects of misinformation from non-expert sources.” He says it can have the same effect on exaggerating the believability of some political groups.

Indeed, Benegal says, the new findings may “be relevant to a lot of other areas where there is skepticism or misinformation about scientific facts.” He says that includes topics such as climate change or biotechnology.

The new study, he adds, also highlights the problem some news outlets create when they look for comments from “both sides” — experts and non-experts — on matters of science. After all, science is about facts. And someone’s personal beliefs won’t change the facts.

What to do

The new findings don’t mean that overconfident people are stupid, Motta says. They may even know a lot about things other than vaccines. And telling people that they’re idiots would never change their minds anyway.

Some people might be willing to consider scientific evidence. Others might not listen. Ethan Lindenberger, 18, of Norwalk, Ohio, faced that problem. His mom wouldn’t let him get vaccinated. She rejected mounds of scientific evidence showing that vaccines are safe. “Her only response was: ‘That’s what they want you to think,’” Lindenberger said at a March 5 congressional hearing in Washington, D.C.

When talking about vaccines with someone, such as a parent, don’t give up, Motta urges teens and tweens. “Make an effort to connect with your parents,” he suggests. “Talk with them on their own terms,” he says, “while staying true to the science.”

If a parent worries about side effects, Motta says, contrast the teeny risk of any true side effect with the much greater danger of getting a potentially lethal disease.

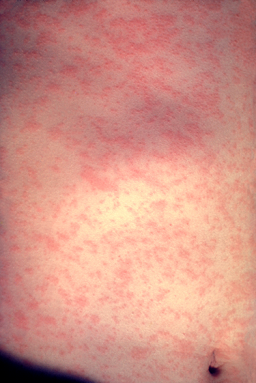

If a parent thinks vaccines are disgusting, Motta suggests that teens talk how getting a dangerous, preventable disease is much more disgusting. Describe the blotchy, ugly rashes of measles or skin scars of chickenpox. Describe the pain and spasms tetanus can cause or yucky diarrhea from rotavirus. Even the throat-clogging mucus from diphtheria (Dip-THEER-ee-uh).

Motta and others are now at work on a new study. They hope it will show this strategy can work. If so, it may one day help health experts and others fight the growing problem of preventable disease.

PBS NewsHour/YouTube