Why trans fats became a food villain

Food science produced a new fat — and then discovered it wasn’t all that good for us

Some sweet foods, such as the sprinkles on this doughnut, get their texture and bland, sweet taste from trans fats — a type of fat made from vegetable oil. But emerging research is showing that these fats aren’t the healthier alternative to butter that they were once made out to be.

JMIU/FLICKR (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On a recent road trip, we stopped at a gas station to fill up our truck’s tank and pick up snacks. Inside the dingy, stale-smelling roadside store, I picked up a packet of thick cookies. The package proclaimed “zero grams trans fat!” Throughout the shop, more products echoed the first. “No trans fats here!” “Now trans fat free!” It’s the same story in stores across the United States. Many baked goods and prepared foods, from doughnuts to burritos, now declare themselves “trans fat free.”

Eating too much fat can cause health problems. But even in moderation, some fats are healthier than others. Now studies suggest that synthetic trans fats — a type made by adding extra hydrogen atoms to the chain-like molecules of vegetable oil — can act like a dietary villain.

Doctors once thought trans fats might be better for health than those found in meats and dairy. And because trans fats are cheap, food companies were eager to substitute them in foods.

But over time, scientists slowly began to realize that artificial trans fats were no healthier than butter or other animal fats. Indeed, they might actually be worse for health. Now, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration — which helps to regulate the foods that go on our grocery store shelves — has declared that trans fats are not “generally recognized as safe,” or GRAS. This means food companies now have less than two years to get rid of them for good.

This series of events might seem like a failure of science. But the rise and fall of trans fats is actually an example of the scientific process at work. Science can yield new and seemingly useful inventions, such as trans fats. But sometimes those things may have unintended side effects.

For a perfect crust, just add fat

Baked goods such as pie crusts and doughnuts need fats. Fats help create a fluffy pastry and moist taste. Until the early 1900s, those fats usually came from animals. Butter comes from cow’s milk. Lard is pork fat. Tallow is fat from beef cattle or sheep. Though they come from different animals, these fats all have two things in common. First, they are solid at room temperature. Second, they don’t quickly become rancid — that is, develop a nasty taste as they undergo chemical reactions with the oxygen in air.

All fats are made of chemicals known as fatty acids. These are long chains of carbon atoms strung together. To be stable, a carbon atom needs to have four other atoms bonded to it. When one carbon atom connects to two other carbons (the ones above and below it in the chain), two bonds are used in those connections. That leaves two free spots on the outside of the chain. Hydrogen atoms can bond at these sites.

In a saturated fat, two hydrogen atoms bond to each carbon atom in the chain, with three hydrogens on the last carbon dangling at the end of the line. Because this fat molecule is soaked in hydrogen, scientists call these fats saturated or fully hydrogenated. These chains of fatty acids are long and straight. That allows them to line up nicely with each other. Their straight-chain structure helps saturated fats stay solid at room temperature. Animal fats such as butter, lard and tallow are saturated fats.

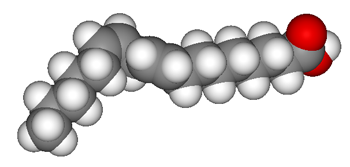

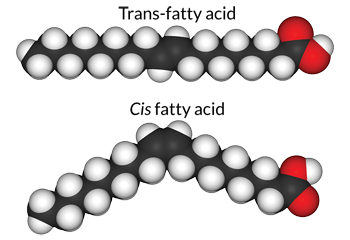

Vegetable fats are unsaturated. That means some of their carbon chains have bonding sites free of hydrogen atoms. In these fats, some of the carbons in the chain use two of their bonds on only one connection. These double bonds leave less room for hydrogen.

Most vegetable fats are also cis-oriented molecules. That means the hydrogen atoms all bind on the same side of the carbon chain. When the hydrogen atoms are evenly distributed on both sides of the chain and there are no double bonds, the chain is straight. But when there are double bonds, the hydrogen atoms line up on only one side of the chain. That makes the chain of atoms bend or kink. These unsaturated fatty acids do not line up well with each other. The end result is that such fats tend to be liquid — oils — at room temperature.

Saturated fats from animals are best for baking. Their stable structure means they can be easily whipped up to hold air — making a frosting frothy and a cake fluffy. The fats also add flavor. But it costs more to raise animals than to grow plants, so animal fats are more expensive than vegetable oils. And that explains what drove scientists to engineer solid fats from vegetable oils.

Playing chemical musical chairs

More than a century ago, the French chemist Paul Sabatier discovered a way to turn unsaturated fats into something that resembled saturated fats. He bubbled hydrogen gas through vegetable oil. But first he added a catalyst — a substance that triggers a chemical reaction. Doing this broke down some double bonds. That allowed more hydrogen atoms to bond with the chain of carbon atoms.

This industrial process is now known as hydrogenation. It replaces double bonds between carbon atoms with hydrogens. If all of the double bonds are replaced this way, the fat will be fully hydrogenated — making a saturated fat. But if the process is stopped early, some double bonds will remain. Food chemists refer to this as partial hydrogenation.

During hydrogenation, something else also happens: The orientation of the bonds changes.

This is how it happens: When hydrogen gas is bubbled up through the fats, “it’s kind of like musical chairs,” explains Sarah Ash. She studies nutrition at North Carolina State University in Raleigh. The hydrogen atoms on the fat chains start in their normal positions, on their carbon “chairs.” Then the bubbling — the “music” — starts and the hydrogens get off of their carbon chairs and run around. Some of the carbon double bonds break. That leaves free spots for more hydrogen atoms to slip into the molecule. When the gas stops bubbling, the hydrogen atoms have to find “chairs,” so that they can quickly bind to available carbons again.

But as in musical chairs, the hydrogens don’t always end up bonded to the same carbon atom onto which they originally had been seated. Instead, they may land on the opposite side of a double bond. Those opposite-side positions are known as trans. Trans-oriented chains are partially hydrogenated, which means they still have some double bonds. But the trans position balances out the carbon chain, making it a straight line, similar to a saturated fat. These “trans fats” line up nicely with each other, just as saturated fats do. And that means trans fats, too, are solid at room temperature.

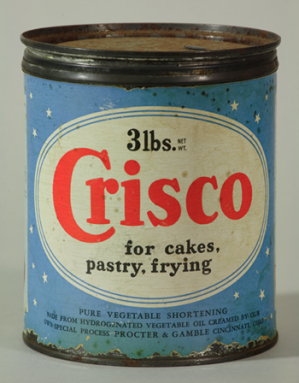

With trans fats, the food industry had a cheaper solid fat to make pie crusts and to fry up potatoes. Soon, these fats began appearing on grocery shelves in products such as Crisco, which used trans fats produced from cottonseed oil. “It was marketed as a better alternative to lard,” Ash says. As doctors began to worry about the effect of animal fats on heart health, artificial trans fats — which were always from plant sources — seemed like a better option.

Trans fats also were less expensive than animal fats. They could sit on a shelf for months without going rancid. And they were seen as being “cleaner,” somehow, than fats from animals. Crisco, after all, was produced in a laboratory — no animals there.

And unlike lard, trans fats didn’t taste like they came from animals. “They were nice, bland white fats,” explains Tom Brenna. He studies food science at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. “If you use lard or butter to make a frosting, it will taste like lard or butter. But partially hydrogenated vegetable oil doesn’t taste like anything.” These new fats were smooth and creamy and lasted as long as animal fats.

Crisco arrived on the market in 1911. In a 1996 national dietary survey, people in the United States were eating almost 6 grams (0.2 ounce) of trans fats per day. That’s almost 10 percent of the recommended daily limit of fat.

The trouble with trans fats

In the 1980s, doctors began to worry about saturated fats, especially ones from animals. There was evidence that people who ate a lot of saturated fats appeared to be more likely to get heart disease. These cardiovascular ailments are conditions that affect the heart and blood vessels.

Concerns about saturated fats arose from their effects on cholesterol (Koh-LES-tur-awl). This is a fatty material that helps to make up the membranes of our cells. The body makes cholesterol. Many foods also supply cholesterol to the body. To move within the body, cholesterol is carried through the blood by packages” known as lipoproteins (LIP-oh-PRO-teens).

One form, known as high-density-lipoprotein (or HDL) cholesterol is considered a “good” type. HDL shuttles its cholesterol to the liver where it will be prepared for excretion from the body. It also can go to organs such as the testes to be made into hormones.

Doctors tend to refer to low-density-lipoprotein (or LDL) cholesterol as the “bad” type. It can build up in arteries and eventually block the flow of blood. Too much LDL cholesterol in the blood is considered a sign that a person might be at risk for heart disease.

Doctors found that people who ate more saturated fats had higher levels of LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol. So doctors began to recommend that people replace more of the saturated fats in their diet with unsaturated ones. Food companies responded to these worries by using more trans fats. These fats were not saturated. They weren’t from animals. And as far as anyone knew at the time, they were safe.

But soon, people began to worry about trans fats, too. In 1990, Ronald Mensink and Martijn Katan, two scientists then at Wageningen Agricultural University in the Netherlands, published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine. It showed that trans fats might elevate LDL cholesterol, just as saturated fats do. “It spurred a tremendous amount of research,” says Alice Lichtenstein. She works at Tufts University in Boston, Mass. As a nutritional biochemist, she studies the chemicals that make up our food and how they interact with our bodies.

After the paper by Mensink and Katan came out, other scientists — including Lichtenstein — combed through data from old studies on trans fats and also launched new studies.

Soon, many different laboratories showed that trans fats raised blood levels of the bad cholesterol. Also worrisome: Unlike saturated fatty acids, trans fats don’t raise levels of that “good” — HDL — cholesterol. Together, high levels of LDL cholesterol and low levels of HDL cholesterol tend to boost the risk of heart disease.

Scientists also found that saturated fats appeared less harmful than they had first thought. In 2015, researchers compared the results of 41 different studies. Saturated fats might not be associated with cardiovascular disease after all, they found. And many of the ways that people used to avoid saturated fats turned out to be counterproductive. Replacing saturated fats with sugar isn’t any better for health. Neither is avoiding all fats.

Doctors now recommend limiting saturated fat to less than 10 percent of all calories eaten. And as much as possible, people are asked to replace saturated fats with unsaturated ones, such as many of the fats in olive and canola oils. The goal is not to replace saturated fats with sugar, and definitely not with trans fats.

Even though scientists continue to debate the health effects of eating saturated fats, all generally agree that manufactured trans fats are harmful. Scientists still are not sure how trans fats affect cholesterol, though. One possibility is that trans fats slow the breakdown of LDL particles, says Lichtenstein. This might make them build up in the blood. But how that might happen remains a mystery.

But the FDA doesn’t have to know exactly how something works to regulate it. In 2003, it issued a ruling that trans fats would get a separate line on nutrition labels, starting in 2006. Getting an extra line on a label doesn’t seem like it should be a big deal. But food companies were not eager to advertise how much of these trans fats a food had. So they quickly worked to make sure they brought it down to zero. “I don’t think customers used the information,” Lichtenstein says. “But I think the companies realized it looked better for their products to be listed as zero trans fat.”

Butter is back

Over time, evidence continued to build that artificial trans fats are not heart friendly. In June 2015, FDA finally declared that partially hydrogenated oils — the artificial trans fats — are not GRAS. By June 18, 2018, companies may no longer sell foods in the United States that contain these fats. Many companies already have removed them.

To do this, though, companies have had to change their recipes.

“They will reformulate with other kinds of vegetable fats, palm oil, coconut oil,” explains Brenna, at Cornell. “These days we … can create plants that will give oil profiles of anything we like.” Just as scientific research discovered trans fats, science is now finding ways to replace them.

Manufactured trans fats may fade from U.S diets, but that won’t automatically make these foods healthy. “Just because a food has zero grams of trans fat doesn’t mean it’s good for you,” notes Lichtenstein. “Trans fat is just one component [of our diet]. Cardiovascular disease is a slowly progressing disease and it starts young.” Lowering risk doesn’t end with ditching trans fats from the diet, she warns. It means eating a healthier diet overall and getting plenty of exercise.

If you eat everything in moderation, Ash says, you may need to worry less about what fat or ingredient is the next diet villain. Cookies or doughnuts — the trans fat-free kind — still can be, as Cookie Monster says, “a sometimes food.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated on November 23, 2016 to clarify the definition of cholesterol.