Wildfires worsen extreme air pollution in U.S. northwest

Smoke from blazes ravaging western states counteracts clean air improvements

The 2018 Carr fire in northern California, seen here outside Redding, threw pollutants into the air for weeks, beginning July 23. The state reported that air quality was “unhealthy” throughout the region affected by this intense fire. One of the biggest in state history, this fire eventually burned more than 175,000 acres and destroyed more than 1,077 homes.

E.L. Karey

The northwestern United States has become an air pollution hot spot — literally. And scientists are blaming the problem on bigger and more frequent wildfires. These disasters spew plumes of fine particles that pollute the sky.

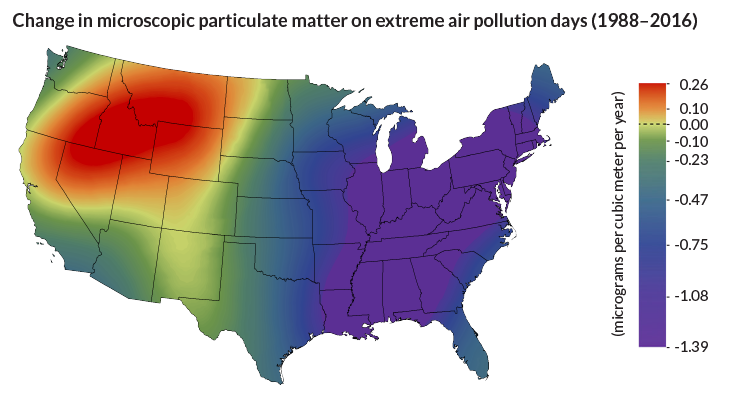

In states from Nevada to Montana, days with the most extreme air pollution are worse now than they were 30 years ago. That’s what researchers reported July 16 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Over the same period of time, smog and haze has tended to decrease across the rest of the country. Laws such as the Clean Air Act, which set rules to limit pollution, have helped. So have laws that limit allowable levels of pollution from vehicles and factories, says Daniel Jaffe. He is an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington in Bothell. He also is one of the new study’s authors.

Climate change has led to a drying of western forests. This has upped the number of local wildfires. That recent increase in large western wildfires has thrown more lung-clogging pollution into the region’s air. The problem is so great now that wildfire pollution has begun overcoming the benefits of air-pollution laws in parts of the affected states, Jaffe says.

Wildfire smoke is filled with fine particles. These nanopollutants are less than 2.5 micrometers wide. (That’s about 3 one-hundredths the width of a human hair.) Such super-tiny solids and droplets can be inhaled deeply into the lungs. That can aggravate breathing problems. Children, the elderly and people with asthma face the biggest risks. But temporarily levels of pollutants in communities near wildfires can get so high that it becomes unsafe for anyone to be outside for long.

Regularly breathing high levels of these fine particles has been linked to an increased risk of chronic health conditions such as heart disease and diabetes.

“When we start to think about people’s health, [these wildfire] events matter a lot,” says Gannet Hallar. She’s an atmospheric scientist who works at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City who did not take part of the new study.

Wildfire pollution is short-lived, but bad

“Most of the year, wildfires aren’t impacting air quality,” notes Jaffe. “But on some of the worst days they are.” And the blazes can hit one community hard, but leave neighboring towns largely unaffected. This intermittent and patchy nature of wildfires makes assessing their role on regional air pollution tricky, he says.

Jaffe carried out the new study with Crystal McClure. She, too, is an atmospheric scientist at the University of Washington. The two looked at daily measurements of fine particles in air at more than 100 rural monitoring sites around the United States between 1988 and 2016. In most places, the data showed a success story: cleaner air over time. But this was not true in the Northwest, an area that now gets hammered hard by wildfires every summer.

The team compared levels of a few specific pollutants. One was black carbon, a hallmark of fires. They also looked at sulfate, a by-product of burning fossil fuels. Black carbon levels had increased over time in the Northwest; sulfate levels didn’t. This trend supported the conclusion that wildfires — not industrial activity — have had a big role in driving the air pollution trend in the western states.

Wildfires weren’t worsening air pollution on an average day in the northwest, the team found. Most days, air quality was fine. Wildfires might affect a given community for only a few days or weeks out of a year. But the bad days have been getting worse over time, the new study found.

Those particularly bad days tended to be in the summer, which is also when wildfires are at their peak.

Levels of fine particles on the handful of days with the worst air quality each year in the Northwest have increased by an average rate of 0.21 micrograms per cubic meter per year.

So, while the overall air pollution situation in the country has improved across the United States, western states now have more work to do, says Jenny Hand. She’s an atmospheric scientist at Colorado State University in Fort Collins who wasn’t part of the study. Wildfires create additional challenges beyond protecting homes and trees. Among these is figuring out how to deal with — or prevent — these more uncontrollable sources of air pollution.