Well-known wildflower turns out to be a secret meat-eater

A deathtrap for small insects sits just beneath its flower

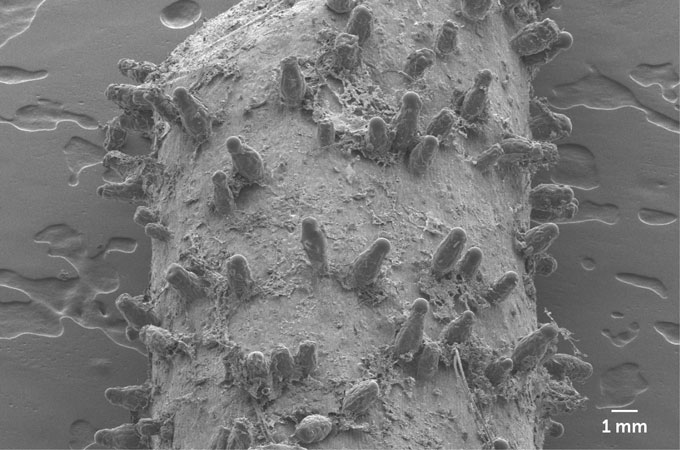

This innocent-looking flower has sticky hairs on its stem that trap and digest small insects. Scientists found this flower growing in Cypress Provincial Park in British Columbia, Canada.

Danilo Lima

Gleaming, gluey, deathtrap hairs have just betrayed the secret identity of a well-known wildflower. It’s a carnivore.

This species of false asphodel looks like a harmless, white-petaled flower. But Triantha occidentalis has special, sticky hairs on its flowering stem. The plant uses its hairs to snare and digest insects. Scientists have known about the plant since the 1800s. But its taste for meat went undetected — until now. Researchers reported the finding August 17 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Sticky hairs aren’t all that unusual. Many non-carnivorous plants use them to defend against pests, points out Sean Graham. A botanist, he studies plants at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada.

This plant has some qualities that other meat-eaters share. It lives in bright, nutrient-poor bogs. It’s also missing a gene that fine-tunes how plants get energy from light. Together, those features felt like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle hinting at a secret hunger for meat, Graham says.

To confirm that, Graham would need to know more. So he became part of a team looking for signs that this wildflower pulls nutrients from insect corpses. Luckily, T. occidentalis grows along North America’s West Coast, from Alaska to California. It can be found even on hikes near Vancouver. “They’re right on our doorstep,” says Graham.

The team started by feeding nitrogen-15 to fruit-flies. Compared to normal nitrogen, each atom of N-15 contains an extra neutron. And once flies ingest it, this tags their bodies with the heavy nitrogen. Next, the researchers attached the flies to the flowering stems of the bog-dwelling plants. Nitrogen-15 is not common in nature. But tests can scan for it and count how much is present in a sample of something — such as tissues of the wildflower.

More than half of the wildflowers’ nitrogen came from the fruit flies, not the soil, Graham’s group found. That amount is similar to what’s seen in carnivorous plants.

What’s more, the wildflowers’ sticky hairs oozed phosphatase (FAAS-fuh-tays). A digestive enzyme, it drives chemical reactions. Many carnivorous plants make phosphatase to digest prey.

Even though carnivorous plants kill and eat insects, they also need to avoid killing pollinators — the critters that help them make seeds and reproduce. That’s why most of the world’s roughly 800 meat-eating plant species have evolved traps and flowers that are set far apart.

But the sticky traps on T. occidentalis sit right next to its flowers. “Putting your traps close to your flowers is, on the surface, a really big conflict,” Graham says. This plants’ hairs might, however, have just the right amount of stickiness. They catch small flies and beetles. They’re not sticky enough, though, to trap bigger pollinators such as bees and butterflies. The plant’s sticky hairs might also hint at how some meat-eating plants evolved. In nutrient-poor soils, it may benefit some plants to use defensive hairs in a different way. Where nutrients are hard to come by, it might pay to use those hairs for carnivory, Graham says. “The insects are being trapped anyway, so might as well use them” — as lunch.