Wind power gets downsized — but in a good way

Broadcom MASTERS finalists develop ways to generate wind power on a personal scale

Modern wind turbines are huge, but some young researchers are working on smaller devices to capture the power of the wind.

RAWPIXEL/ISTOCKPHOTO

By Sid Perkins

WASHINGTON, D.C. — In many places, wind power is getting to be a big deal. Already by last year, some 4.7 percent of all U.S. electricity came from wind turbines. Farms of these wind-power devices are spreading across the planet. And some are becoming true giants. The largest are taller than 60-story skyscrapers. Just one can produce enough electricity to power more than 1,500 homes.

But some researchers are bucking this trend. They’ve chosen to go small for uses that are also tiny. For instance, a small-scale windmill might be all that’s needed to run a single sensor that will only gather some type of data once every few minutes, if that often.

Such low-cost generators could be particularly useful in remote spots, where it would be too expensive and troublesome to run power lines. Or they might replace batteries that would run down and then need frequent recharging or replacement.

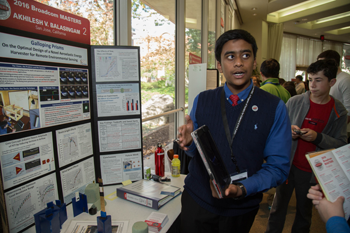

And professional researchers are not the only ones trying to develop these devices. Two of this year’s Broadcom MASTERS finalists are also working to harness wind power for these tiny needs.

MASTERS stands for Math, Applied Science, Technology and Engineering for Rising Stars. The Broadcom MASTERS competition brings together 30 middle-school students each fall. The program was created by Society for Science & the Public, which publishes Science News for Students. Broadcom Foundation sponsors it. Part of the competition is based on research the students entered the year before in a science fair.

Harnessing the wind

There are many sorts of sensors that can operate on low power, explains Heath Hofmann. He’s an electrical engineer at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. That’s especially true for sensors that operate only infrequently, he notes. “Scientists are still trying to figure out all the possible uses there might be for such sensors,” he says.

Some researchers have used low-power sensors to monitor wildlife or environmental conditions on the seafloor. Others use such sensors to monitor the vibrations of bridges as traffic passes across them. Changes in those vibrations over time, he notes, could signal that parts of the bridge have worrisome cracks that are growing in size. Still other engineers have proposed using remote sensors to scout signs of corrosion in energy pipelines.

Before anyone can rely on such sensors, however, they’ll need a power source such as the tiny systems being developed by this year’s Broadcom MASTERS contestants.

To create his, Akhilesh Balasingam, 13, of San Jose, Calif., used a piezoelectric material. When such materials flex, electrons inside them move to generate an electric current. (The “piezo-” prefix comes from the Greek word piezein. It means “to squeeze” or “to press.”)

The teen glued a strip of the material roughly 2 centimeters (about an inch) long to a flexible strip of brass. Then, he stuck a tough plastic weight onto the end of the metal strip. Finally, he hung that strip from the underside of a board so that the weight could swing back and forth like a pendulum whenever the wind blew. That motion caused the piezoelectric material to bend and flex. This created a small amount of electric current.

Engineers use large wind tunnels to analyze the airflow around models of devices, such as airplanes and rockets. Akhilesh built a small wind tunnel that was powered by a household fan (the same type people use to cool off in hot weather). To make sure the airflow was straight and not swirling, he had the wind blow through a filter made from drinking straws. The long paths through the straws helped straighten the flow so there would be no turbulence.

Finding the right mix of materials to produce the most power required some tinkering. For instance, the teen applied different amounts of electrical resistance to his device to test its power output. (The more light emitting diodes, or LEDs, he hooked up to the device, the more resistance the circuit had.) Finally, Akhilesh varied the size and shape of the weight attached to the end of the metal strip. Some were shaped like small boxes. Others were shaped like a solid triangle.

The device could produce power at winds speeds as low as 1 meter per second (or about 2.2 miles per hour). The best design produced between 600 and 700 microwatts of power. That sounds like a very small amount. And it is. The small bulb in a nightlight can consume more than 5,000 times as much power as Akhilesh’s device produces. But some sensors require only 100 microwatts of power, the teen points out. So his device could power thousands of those. A device such as his might be used to power sensors that measure moisture levels in forest soils. Or it might run sensors that track those bridge vibrations caused by traffic, he suggests.

A roadside breeze

Rachel Pizzolato, 12, of Metairie, La., designed a system that would work even when no winds blow. It’s powered by traffic.

As a vehicle passes, it kicks up dust — and a good bit of wind. Big trucks can create enough wind to almost knock someone down. Such breezes could be a ready source of electrical power, particularly in places where traffic is nearly nonstop, she notes.

The trick, though, is capturing that energy. Although roadside wind is plentiful, Rachel’s first design didn’t work. She started out by mounting a bicycle wheel on a small pole horizontally (giving it the same orientation as a bike laying on its side). Then, she attached eight large flaps of cardboard to the rim of the wheel, sticking out so that the wind could spin them. To test her device, Rachel had her dad drive by.

Yet the wheel didn’t spin.

So Rachel scouted for the problem. She soon realized that the flaps on one side of the wheel captured the wind just as effectively as those on the other side. Because those forces canceled each other out, the wheel remained motionless. No rotation equals no power from her mini windmill.

So Rachel changed the orientation of those flaps. Instead of having them stick straight out from the rim, she bent them so that they all projected from the rim at a 30-degree angle. (Think of a clock. If a line pointing directly outward from the rim is pointing toward 12, the flap would be pointing toward 11 o’clock.) Now the flaps on the left side were pointed slightly into the wind. Those on the right side pointed slightly away from the wind.

That difference now allowed the wheel to spin easily when the breeze from a passing car blew past it. And as the windmill spun, a small device mounted on the windmill’s pole turned the motion into electricity. (Such devices are called generators, because they use the relative motions of magnets to generate electricity.)

To test her windmill, Rachel set it next to the road and had her dad drive the family car past it. Her dad got up to speed and then set the cruise control. In this way, he could be sure that the car maintained the same speed each time it passed her device.]

Story continues below video.

Rachel’s dad drove by at speeds ranging from 24 to 56 kilometers per hour (or 15 to 35 miles per hour). Rachel then measured the highest voltage produced by the windmill during 100 trials. (Volts are a different measure of electricity than watts. Voltage measures the electrical potential between two points in a circuit. Watts considers the amount of electrical current passing between those points as well as the voltage.)

At a slow drive-by speed, the car got the windmill generating an average of 20 millivolts. High-speed tests caused the spinning windmill to generate roughly 77 millivolts. Again, these amounts seem small. But because many cars may pass a particular spot throughout a day, any power generated by such a windmill could add up to a substantial amount, Rachel notes.

The students have not yet designed a way to store the power generated by their devices. But Akhilesh says that should not be hard. A battery is one option. Better yet might be a device called a capacitor. It can store electrical energy and then release it again as needed, just as a battery would, he says. But batteries often lose their ability to hold a charge over time, the teen notes. They also need to be recycled or disposed of in special ways. Capacitors typically don’t have such problems, he points out.

These tiny devices also could send their energy into the power grid, Rachel says. And then these tiny windmills could help power anything from your refrigerator to a charger for your cell phone.