Your inner Neandertal

New study finds some DNA in modern humans was passed down from Neandertals

Many modern humans might be walking around with a little caveman inside. Inside their cells, that is.

|

|

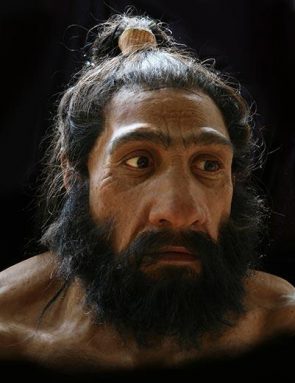

Artist John Gurche created this bust showing what a Neandertal may have looked like.

|

| © 2010, John Gurche; Smithsonian Institution |

The Neandertals are ancient members of the human family tree. This species, Homo neanderthalensis, appeared about 300,000 years ago. Our species, Homo sapiens, appeared about 250,000 to 200,000 years ago. No other extinct species is a closer relative to humans than are the Neandertals. By 30,000 years ago, this species had vanished.

Neandertals probably walked on two legs and lived in what are now Europe, Asia and the Middle East. They may have looked a lot like modern human and lived in some of the same regions. Still, scientists have long thought that Neandertals and early modern humans had little to do with each other. A new study suggests that’s wrong. These two species may have become close enough to have children together.

Even now, researchers can learn a lot about Neandertals by studying genetic information they left behind in their bones.

For the new study, researchers collected genetic material from ancient Neandertal bones. Then they compared it to genetic material in modern people (Homo sapiens). The scientists found evidence that long ago, members of the two species mated. Today, 1 to 4 percent of the DNA in people from Europe and Asia has been inherited from their ancient Neandertal ancestors.

“It’s a small, but very real proportion of our ancestry,” David Reich told Science News. Reich is a geneticist who studies the genes of particular populations. He works at the Broad Institute, which is at both MIT and Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass.

“Neandertals are not totally extinct; they live on in some of us,” Svante Pääbo told Science News. Pääbo leads a large group of scientists who do research aimed at understanding Neandertal genes.

Reich was surprised to see the DNA link between the ancient cavemen and modern people. One year ago, a team of scientists (including Reich and Pääbo) analyzed and reported the entire genetic code for Neandertals.

|

|

These three fragments of Neandertal bones yielded the first DNA evidence of human-Neandertal interbreeding.

|

| Max-Planck-Institute EVA |

The entire genetic code of a species is called its genome, and it is a list of all the important genes in the species’ DNA. These genes contain the instructions for how to build proteins. Those proteins perform specific functions in a cell. When scientists produced the first version of the Neandertal genome, they said it was very unlikely that Neandertals and humans had ever interbred.

For the new study, Reich and his colleagues used genetic material from the bones of Neandertals, found in a cave in Croatia. The scientists compared those genes to the genomes of five modern humans from different parts of the world: China, France, Papua New Guinea, southern Africa and western Africa.

The results were surprising: Not everyone had the same Neandertal connection. The two people from Africa had no Neandertal DNA. The other three groups of people did — even though Neandertals never lived in China or Papua New Guinea. The modern people from those areas had just as much Neandertal DNA as the person from Europe.

Since modern Africans do not have Neandertal DNA, the scientists think that Neandertals and humans began to interbreed after humans left Africa and entered the Middle East (before moving on to colonize the rest of the world). The researchers aren’t sure how long the two species mixed.

Although the new study is exciting for geneticists, other scientists are less impressed. Some scientists say that Neandertals and modern humans are so similar they shouldn’t even be considered separate species. Archaeologists have also found skeletons in Europe that look like both Neandertals and modern humans — which also suggested the two species mixed.

“After all these years the geneticists are coming to the same conclusions that some of us in the field of archaeology and human paleontology have had for a long time,” says João Zilhão of the University of Barcelona, Spain. “What can I say? If the geneticists come to this same conclusion, that’s to be expected.”

John Hawks is an anthropologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Anthropologists study the behavior and development of human beings. Hawks points out that the new study tells us that many people have a distant relative that was a Neandertal.

“It’s impossible to talk about them as ‘them’ anymore,” he says. “Neandertals are us.”