Zika birth defects: Concerns spread from head to toe

New, long-term problems are being linked to Zika infections

Scientists and public health officials are finding more ways that the Zika virus can harm unborn babies.

Master Sgt. Brian Ferguson/U.S. Air Force/Airman Magazine/Flickr (CC-BY-NC 2.0)

By Meghan Rosen

Vanessa van der Linden has spent the past year caring for patients at the heart of Brazil’s Zika epidemic. She works at Barão de Lucena Hospital, in Recife. And many symptoms in her youngest patients worry her.

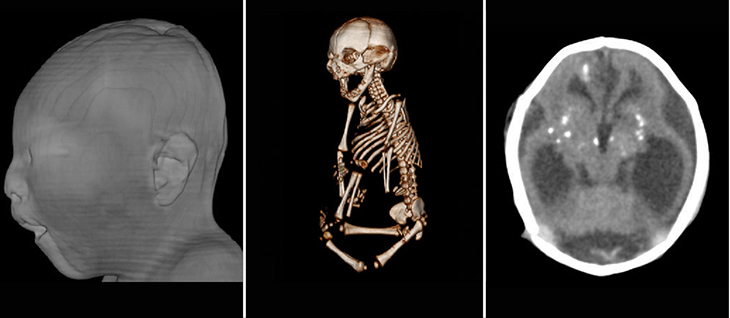

As a pediatric neurologist, Van der Linden specializes in children’s brains and nervous systems. And she was one of the first researchers to link the Zika virus to a birth defect known as microcephaly (My-kroh-SEFF-uh-lee). The term means “small head.” Afflicted babies are born with heads that are misshapen and smaller than normal. Sometimes their foreheads slope backward.

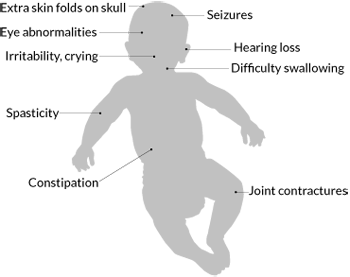

In the past year, microcephaly has emerged as the most common birth defect linked to Zika . But a host of other symptoms may also show up. Van der Linden has seen babies that cry for 24 hours straight. Some experience muscle spasms, extreme irritability and difficulty swallowing.

Emerging research now indicates that microcephaly is far from the only worry that parents of Zika-exposed children may face. Van der Linden described the growing list of health risks on September 22 at a workshop hosted by the National Institutes of Health in North Bethesda, Md.

Right now, no one knows how big the full problem is, says Peter Hotez. He is a pediatrician and microbiologist at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Tex. “That’s the big unknown,” he says. “There’s probably a spectrum of illness,” similar to autism, he says. And some symptoms, such as learning disabilities or developmental delays, might take years to emerge. Public health officials have been warning for months that exposure to the virus during pregnancy might be linked to even more Zika problems. Those health impacts now appear to comprise a list that affects the body from head to toe. Doctors have begun calling it congenital Zika syndrome.

Brazil is facing this challenge now. Zika also presents a growing threat in the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico. As of September 23, Puerto Rico reported 22,358 confirmed Zika infections, including 1,871 pregnant women.

Carmen Zorrilla works at the University of Puerto Rico’s Maternal-Infant Studies Center in San Juan. This obstetrician-gynecologist has examined some of these women and their babies. She now argues that it is essential that the medical community watch all babies exposed to Zika in the womb — including those with no visible birth defects.

Even when they look healthy at birth, she says, “it doesn’t mean they’ll be okay [later].”

A parade of problems

Zorrilla’s concern comes from a growing list of problems being linked to the virus. At the workshop, she described one of the first Puerto Rican babies born to a mother diagnosed with Zika. The baby didn’t have microcephaly. She did have one unusual problem, however: This newborn could not open her eyes.

A bad case of pinkeye, also known as conjunctivitis (Kon-JUNK-tih-VY-tus), left the baby unable to open her eyelids each morning on her own — even 27 days after birth!

Zorrilla can’t say for sure whether the problem was related to Zika. But “it really concerned me,” she said. “This is the first baby I’ve seen with conjunctivitis that lasted for so long.” The case may be a clue that Zika’s harm to the body is widespread.

Alberto de la Vega is another obstetrician-gynecologist at the University of Puerto Rico. Zorilla shared his early results from ultrasound scans of 228 pregnant women in Puerto Rico. Each had a confirmed Zika infection. Those scans turned up brain abnormalities in 13 fetuses. One of those babies had microcephaly. Most of the rest had somewhat small heads, although “still within the normal limits,” Zorrilla said. Fetal measurements of the leg bones and stomach show that the rest of the body was growing normally. For now, she says, it isn’t yet clear what these findings mean.

Other scientists have begun linking new symptoms to Zika infections in the womb. For some affected babies, Zika seems to have hurt their hearing. Among 70 Zika-exposed infants with microcephaly, one in every 10 had some hearing loss. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in Atlanta, Gal., shared the disturbing statistic in a September 2 report.

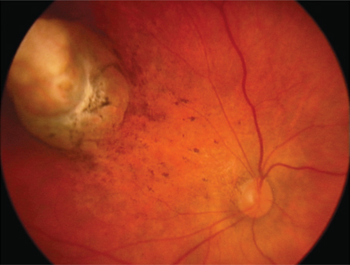

Zika also can affect the eyes. Researchers studied 29 Brazilian babies with microcephaly. More than one in every three had some eye oddity. Impacts ranged from patchy pigments (coloring) to withered tissue. Bruno de Paula Freitas and his colleagues described these eye problems in the May issue of JAMA Ophthalmology.

Van der Linden has also seen a deformity called arthrogryposis (ARTH-roh-GRIP-oh-sis). It can leave a child’s with “contractures” — joints stuck in contorted positions. Their arms and legs, for instance, may not bend normally. It has shown up even in babies without microcephaly. She and her colleagues now suspect that it might trace to the virus infecting the babies’ motor neurons. These are the nerve cells that relay messages from the brain to the muscles. They reported this finding August 9 in BMJ.

Microcephaly or other brain defects may eventually develop even in babies born with normal size heads. Van der Linden saw one mother who brought in her five-month-old. She was worried that her baby wasn’t developing normally. Scans of the baby’s head showed “the same pattern of brain damage” as seen in children with congenital Zika syndrome, van der Linden reports. This included a malformed cerebral cortex, which is the wrinkled outer layer of the brain. The brain also contained strange lumps of calcium. These are known as calcifications.

Story continues below image.

Invading the brain

Scientists still don’t know exactly how Zika damages the brain. But they have some ideas.

Marco Onorati is a brain scientist at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. He and his colleagues found that the virus can invade and kill two important types of brain cells. One type is known as neuroepithelial (NEUR-oh-ep-ih-THEE-lee-ul) stem cells. These can develop into many different types of brain cells.

Radial glial cells are a second type of brain cell that Zika can kill. Their loss is important because these cells in a newborn can make nerve cells, or neurons. These cells also help guide those nerve cells to their proper places in the brain.

Zika also blocks the radial glial cells from splitting into new cells. The Yale scientists described their disturbing findings September 6 in Cell Reports.

Stem cells and new neurons are crucially important in the brain of a developing baby, says Hotez, the Baylor pediatrician. These cells build the structures responsible for thought and learning and memory. As such, he concludes, “This is a virus that blocks the development of the fetal brain.” And that, he adds, is “about the worst thing you can possibly imagine.”

But the unborn might not be the only children at risk, he notes. “Kids in the first years of life also have growing, developing brains,” he points out. “What if they get infected with Zika?”

It’s not an easy question to answer. But another disease does offer clues.

Like Zika, malaria is another mosquito-borne disease that affects many parts of the body. In children, a condition called cerebral (Seh-REE-brul) malaria may be linked to mental health diseases. These include attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, antisocial behavior and depression. Researchers described these disorders, last March, in Malaria Journal.

So researchers will need to scout for long-term troubles even in Zika-exposed babies who had no obvious symptoms at birth. “We don’t want to make families too scared,” says Sonja Rasmussen, who works of the CDC. “But we do recognize the possibility of later-on seizures or developmental delay.” Seizures are uncontrolled electrical fireworks in the brain. Developmental delays refer to slower than normal acquisition of pivotal skills by children. These may range from crawling and speaking to playing, learning to read and more.

For an example of such delayed effects, researchers can look at another often-hidden viral infection that causes microcephaly. It’s known as CMV, which is short for cytomegalovirus (Sy-toh-MEG-uh-low-VY-rus). As with Zika, it can infect babies in the womb. Most CMV-infected babies show no symptoms. But even kids who at first appear fine may develop problems in coming years. These may include intellectual disabilities, hearing loss or cerebral palsy. Researchers in Japan described these long-term effects of fetal CMV infections in the October Brain and Development.

Most people infected with Zika don’t show any visible signs. This makes it nearly impossible to know how many pregnant women (and their babies) might have been infected.

In the Americas, at least, the number is likely to be enormous. Indeed, Hotez at Baylor predicts that tens of thousands of children may eventually suffer some sort of brain or behavioral illness triggered by Zika. He described these concerns in the August issue of JAMA Pediatrics.

Van der Linden can’t say whether the babies she has seen will develop learning disabilities, mental illnesses or other more subtle problems associated with brain processing. Right now, most of her patients are still between 9 months and a year old. But she plans to follow them for years. “We need time to better understand the disease,” she points out.

Hotez agrees. To figure this out, he predicts, it’s going to take a generation of pediatric brain specialists and infectious disease experts.