Zika vaccines look promising

So far they have been tested only in animals

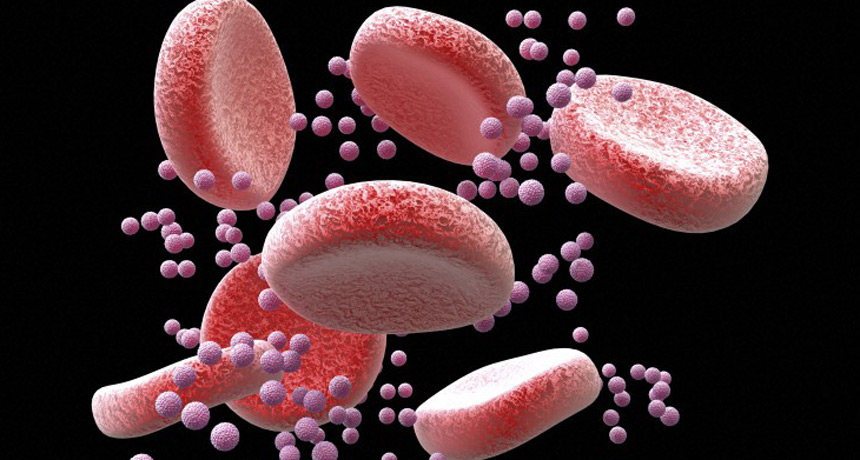

A computer graphic depicting Zika viruses present in the blood of an infected individual. New vaccines may make people better able to resist Zika infections.

Maurizio De Angelis. Wellcome Images /Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

By Meghan Rosen

For the past few months, an outbreak of Zika virus in the Americas has put the globe on high alert. An epidemic of infections — some with potentially devastating side effects — has raced through Brazil and beyond. High numbers of new cases have been emerging throughout Rio de Janeiro, site of this summer’s Olympic Games. Not surprisingly, there has been a race to create a Zika vaccine — a drug to protect still-unexposed people from this mosquito-borne virus. But in this vaccine race, researchers face a marathon, not a sprint.

A vaccine that’s safe and ready to use in people could take years. That means it might not be available until long after the current epidemic is over. Last week, though, several bits of good news emerged. Scientists announced that two candidate vaccines show promise.

Just a single shot of either protects mice from the Zika virus. That’s what Dan Barouch and colleagues reported June 28 in Nature. This vaccine researcher works at Harvard Medical School, in Boston, Mass.

One vaccine comes from an inactivated form of the virus. That means it is a type that cannot cause the disease. The other vaccine uses snippets of Zika DNA. Both vaccines prevented infection by a strain of Zika that has been infecting people in Brazil. Those vaccines protected mice for at least two months, Barouch said at a news briefing on June 27.

“These findings certainly raise optimism that the development of a safe and effective vaccine against Zika virus for humans may be successful,” he said. Tests in people, he said, “should proceed as quickly as possible.” And indeed, the safety of both candidate drugs is due to be tested in people this fall.

In late June, a different DNA-based vaccine also got the green light for testing in people. It has been developed by two drug companies.

Monkey study supports vaccine prospects

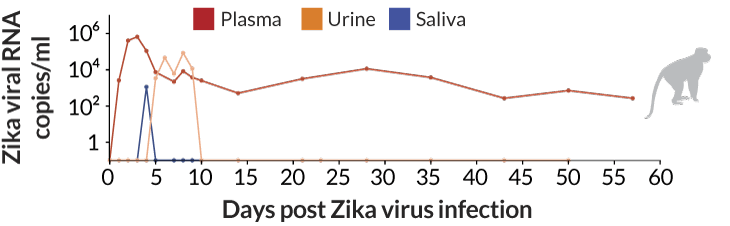

Another research team, led by Dawn Dudley at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, infected eight rhesus macaque (REE-sus Mah-KAK) monkeys with the Zika virus. Afterward, the scientists measured virus levels in the blood and other fluids. After the infection had passed, the team infected three of the monkeys again. This time, none showed signs of Zika in blood, urine or saliva — even 28 days later.

Dudley’s group reported its findings June 28 in Nature Communications.

In fact, Zika is a big concern for pregnant women. A growing body of data shows that an infection early in pregnancy can permanently harm a developing baby’s brain. The bad news, Dudley’s team now finds, is that pregnancy seems to increase how long a Zika infection lingers in the body.

Her team infected monkeys with Zika. Those that were not pregnant cleared the virus in about 10 days. But the germs hung on far longer in pregnant monkeys. In one case, they showed up in the blood for almost two months (57 days).

(Story continues below graph)

The longer mothers have the virus, “the more severe the fetal infection might be,” said David O’Connor. That’s the fear anyway, says this coauthor of the study. He too works at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. To find out whether it’s true, he noted, more studies must be done.

Risks to babies

Earlier this year, studies linked a mother’s Zika infection early during pregnancy to a very serious birth defect. Called microcephaly (My-kroh-SEFF-uh-lee), it is a small and underdeveloped brain. Now, a Brazilian team has shown that’s not the only risk to babies.

Lavinia Schüler Faccini works at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil. Her team has been following 83 babies whose mothers appeared to get infected while they were pregnant. At least 92 percent of the babies showed abnormalities, they found.

Faccini presented her group’s findings June 29 in San Antonio, Texas. She spoke at the annual meeting of the Teratology Society. (Teratology is the study of birth defects.)

Meanwhile, as the Zika virus has been spreading north out of Brazil and into Colombia, more cases of microcephaly have started showing up there. Many conditions can lead to this birth defect. Some small number of cases would occur even in the absence of Zika. But between June 12 and 18, five new cases showed up in babies of moms who had been infected. So far, Colombia has reported 11 such cases of Zika-linked microcephaly.

Before Colombia’s recent report, the number of cases had hovered near the normal, low background levels, notes Yaneer Bar-Yam. He’s a scientist who runs the New England Complex Systems Institute in Cambridge, Mass. The recent uptick in Colombia’s microcephaly cases is “strong evidence” that Zika is responsible, he says.

Bar-Yam and his colleagues reported their preliminary analysis June 27, on the institute’s website. The researchers now estimate that Colombia could see 200 more microcephaly cases in the next two to three months.

“If we get a whole bunch more cases,” Bar-Yam says, “we will definitely see that Zika is causing microcephaly.” But, he adds, “if we don’t see those cases, then we’ll have to reevaluate.”

Word Find (click here to enlarge for printing)