‘Zombie’ wildfires can reemerge after wintering underground

Climate change may make these not-quite-dead fires more common

A forest fire burns in the distance in Canada’s Northwest Territories. New research suggests that zombie fires, which smolder underground through winter months, could increase as climate change accelerates in areas like Alaska and other parts of North America.

Sherry Galey/Moment Open/Getty Images Plus

Winter usually kills most wildfires. But in the far North, some forest fires just don’t die. Think of them as zombies: Scientists do.

After warmer-than-normal summers, some fires can lurk, hidden, through the winter. The next spring, flames can emerge, seemingly from the dead. These “zombie fires” tend to be rare, concludes a new study in the May 20 Nature. But sometimes they can have an oversized impact. And zombie fires may become more common as the world warms, the study warns.

Zombie fires hibernate underground. Blanketed by snow, they smolder through the cold. Fueled by carbon-rich peat and Northwoods soils, most of these hidden fires creep less than 500 meters (1,640 feet) during the winter. Come spring, the fires reemerge near sites they had charred the season before. Now they turn to burning fresh fuel. And this may happen well before the traditional fire season would have begun.

Zombie fires had been known mostly from firefighters’ stories. Few scientists studied them. Until, that is, details in some satellite images tipped off one research team.

Where flames broke out proved the clue

Rebecca Scholten studies Earth systems at Vrije University Amsterdam in the Netherlands. Her team had noticed an odd pattern. “Some years, new fires were starting very close to the previous year’s fire,” Scholten explains. The new observation prompted these researchers to wonder how often fires might survive the winter.

They started by combing through firefighter reports. Then they compared these with satellite images of Alaska and northern Canada from 2002 to 2018. They were scouting for blazes that began close to fire scars left the year before. They also focused on blazes starting before midsummer. Random lightning or human actions spark most Northwoods fires, Scholten says. And those fires typically occur later in the year.

Over those 17 years, zombie fires accounted for less than one percent of the total area burned by forest fires. But rate changed, sometimes a lot, from year to year. In 2008, for instance, the team found one zombie fire in Alaska had burned about 13,700 hectares (53 square miles). That was more than one-third of the entire area burned in the state that year.

One clear pattern emerged: Zombie fires were more likely, and burned larger swaths of land, after very warm summers. High temps may allow fires to reach more deeply into the soil, the researchers note. Such deep burns are more likely to survive to spring.

Back from the dead

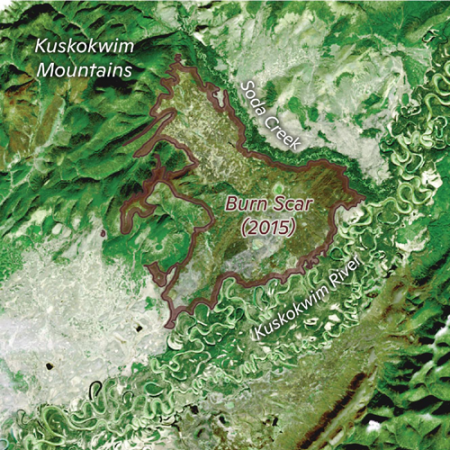

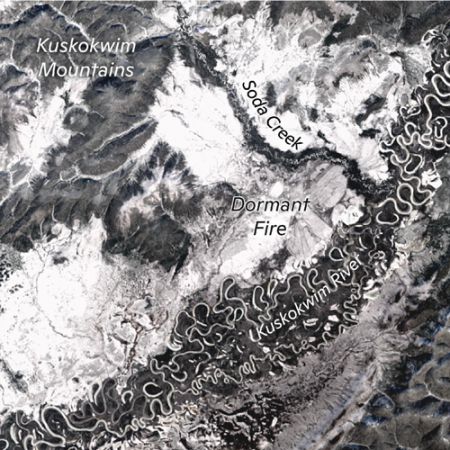

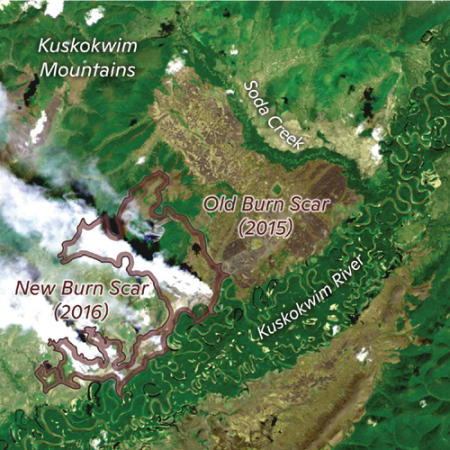

Zombie fires persist underground through winter, emerging the next spring near the previous year’s burn. Here, the area burned by a 2015 Alaska forest fire is outlined on the left in a satellite image. The fire went dormant that winter (center), and reemerged in 2016 close to the old burn scar (outlined in the right image).

September 24, 2015

April 7, 2016

May 30, 2016

The role of a changing climate

This means the zombie threat could grow with climate change. Forests in the far North already are warming faster that the globe’s average. With that, Scholten says, “We’re seeing more hot summers and more large fires and intense burning.” That could set the stage for zombie fires to become a bigger problem, she worries. And the region’s soils hold a lot of carbon — maybe twice as much as Earth’s atmosphere. More fires here could release huge amounts of greenhouse gases. That would drive a cycle of more warming and even higher risk of fires.

“This is a really welcome advance which could help fire management, says Jessica McCarty. She is a geographer at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, who did not take part in the study. ”Knowing when zombie fires are more likely to occur could help guard against that,” she says, by warning when extra vigilance is needed. After extra-warm summers, firefighters would know to scout for zombie flames.

Spotting fires early also will help protect these fragile landscapes that store a lot of climate-warming gases.

“Some of these soils are 500,000 years old,” McCarty says. Due to climate change, he notes, “areas we thought were fire resistant are now fire prone.” But better fire management can make a difference, she adds. “We’re not helpless.”