Zooming In on the Wild Sun

A close look at the sun reveals a chaotic, ever-changing surface.

When you watch the sun set, it looks like a smooth, orange circle sinking below the horizon. But the sun turns out to be a much wilder place when you take a closer look.

|

|

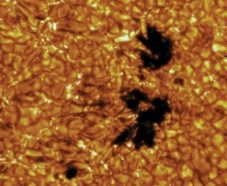

These beads are vast gaseous granules on the sun’s surface. A granule lasts 6 to 10 minutes. Among the granules are sunspots (dark patches) and faculae (bright areas).

|

| T. Berger/Lockheed Martin Solar and Astrophysics Lab. |

The sun’s surface is covered with massive, bumpy structures called granules. Made of incredibly hot gas, each granule is the size of Texas and lasts for about 6 to 10 minutes. The granules are always changing shape, disappearing, and reappearing on the sun’s chaotic surface.

Using a special telescope for looking at the sun, scientists have now taken the most detailed pictures of these granules so far. The pictures show that the granules are covered with canyons and plateaus: billions of giant Grand Canyons with walls up to 100 kilometers tall.

The sun goes through a pattern of changes every 11 years, including a period when it is covered with dark patches called sunspots. You might think the sun would be a little dimmer during this phase—but instead, it gets brighter. Scientists know this is because of very bright structures, called faculae, found among the granules. Faculae is Latin for “little torches.”

Most scientists think the faculae are big tubes sunken into the sun’s surface, like a rabbit’s burrows. But in the new images, the faculae look like enormous walls.

The more scientists learn about these faculae and other structures on the sun’s surface, the better they will understand how the sun’s brightness changes over the years.

This is important because even tiny changes in brightness might affect Earth’s climate. Our wild sun may be modifying temperatures on our planet just enough to give us a few centuries worth of cooler or warmer weather.—S. McDonagh

Caution: Never look at the sun directly. Permanent eye damage can also result from looking at the disk of the sun through a camera viewfinder, with binoculars, or with a telescope.

Going Deeper:

McDonagh, S. 2003. Solar terrain: Revealing the sun’s complex topography. Science News 163(June 28):404. Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/20030628/fob3.asp .