Teen designs belt to hold down a sea turtle’s bubble butt

Affected turtles can end up permanently afloat after a boat strike; this teen wants to right them again

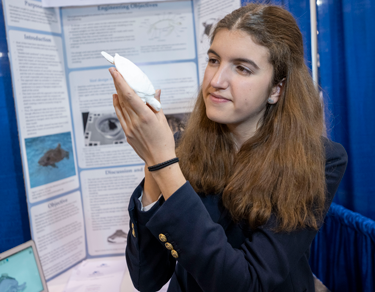

Sea turtles like this one can't survive in the wild after they've been injured by boats. A teen has developed a new vest that she hopes will set them free.

The Turtle Hospital

PHOENIX, Ariz. — Getting hit by boats can make a sea turtle float. While the animal is still alive, it can’t dive, leaving it in constant danger. Now, Gabriela Queiroz Miranda, 18, has invented a device to help an injured turtle dive again. She’s designed a weighted turtle vest.

Gabriela is a senior at Minnetonka High School in Minnetonka, Minn. But she first encountered injured sea turtles while living in Miami, Fla. Back then, she visited the Turtle Hospital in Marathon, Fla., where she learned about “bubble butt syndrome.”

It sounds funny. It’s not. The impact of being hit by boats can drive air inside a turtle’s shell. If the air gets trapped near the back of the turtle, its rear end floats. Once this happens, “There’s no way to get the air out,” Gabriela says. “It’s permanent.”

A floating turtle is not a good turtle. They can’t dive away from dangers (such as more boats). It also can make it difficult for a turtle to feed. “Most end up dying [from the condition],” the teen explains.

Affected turtles that get rescued can never be released back into the wild. To allow them to dive, rescue workers glue weights to the sea turtle’s shell. That weighs the animal down so it can swim normally. But it’s only a temporary fix. The turtle’s shell is made of plates called scutes. These are made of keratin, the same protein that makes up your hair and fingernails. Sea turtles shed old scutes and grow new ones. And every time they do, the weights that are attached to them fall off leaving their butt to float again.

The memory of injured sea turtles stayed with Gabriela after she moved to Minnesota. In a research class at her school, she decided to combine her concern for these turtles with her love of engineering.

Gabriela set out to design a weighted vest that would attach securely to a sea turtle, yet still allow it to move easily and shed its scutes. “I wanted to make it simple enough that any researcher at an aquarium would replicate it for their individual needs,” she says. It would have two key features. First, she wouldn’t cover the entire top of the shell (so there would be space for scute shedding). Second, she’d keep an open back so as the water flows through the vest, the scutes can come out, always leaving the weight on top.

To design her vest, Gabriela worked with Voldetort, a pet mud turtle in her classroom. She carefully used a scanner to create a 3-D model of the animal. “He is a squirmish turtle,” she notes. So the teen checked her numbers with a tape measure and her smartphone. Then she put these measurements into a computer program to design a weight belt.

The teen used a 3-D printer to make a very thin model (with no weights) to test its fit on the turtle. Gabriela then clipped the first prototype to the sides of Voldetort’s shell. The belt had a pouch on the top to hold weights to make the turtle’s butt sink.

It worked. But Gabriela wasn’t satisfied.

If the shell was too damaged, she says, there might not be much to clip onto. She discussed her questions with George Balazs. He’s a scientist who has studied sea turtles at the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center in Honolulu, Hawaii. This center is run by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

With a 3-D scan of a green sea turtle that she found online, Gabriela designed a new vest. This version wraps around the turtle and clips in front, “like a belt buckle,” she says. There’s still space on top for turtles to shed scutes. She also added another pouch. This allows her to balance weights on either side of the shell.

Gabriela brought her vests here to the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. This yearly fair was created and is run by Society for Science & the Public. (The Society also publishes Science News for Students.) ISEF brings together more 1,800 students from 80 countries. This year, it is sponsored by Intel.

The next step, of course, is fitting the vests on real sea turtles. Now, Gabriela is seeing what measurements she might need to modify. Then she plans to send the vest to Hawaii where Balazs can test it on sea turtles in the lab. If it works well, Gabriela hopes that the vests might allow some rescued sea turtles to keep their bubble butts down — and at last return to the wild.