Two teens pull DNA from birds out of the air

Their new technique could help scientists track birds, using the DNA they leave behind

This is a brown hawk-owl, one of the species whose DNA two Japanese teens were able to detect with their new device. They unveiled that device at the 2019 Intel ISEF science competition.

Aaron Maizlish/Flickr (CC BY-NC 2.0)

PHOENIX, Ariz. — When animals travel, they leave bits of themselves behind. Fingerprints and feathers, skin cells and fur. Those bits contain DNA. For some time, scientists have been able to track down this environmental DNA — or eDNA — in soil and in water. Now, two teens have figured out how to also extract it from the air. They hope to use it to track rare birds — even ones people may never see.

Yuma Okamoto,17, and So Tsukamoto, 17, are seniors. Both attend Shizuoka Prefectural Kakegawa-Nishi High School in Kanegawa, Japan. They had previously detected eDNA in water. But when they heard their science teacher, a bird breeder, talk about the debris his animals left behind, the two began to think that eDNA might be in air, too. Their teacher had explained “that bird cages became very dirty with bird sebum,” Yuma says. Sebum (SEE-bum) is an oily substance that birds secrete and use to keep their feathers in good flying shape.

Birds also shed some sebum as they fly. Yuma and So reasoned that they might be able to detect where birds have been by scouting for the eDNA that had come from the sebum shed as a bird flew or perched.

In particular, they wanted to look for signs of owls. “They are nocturnal [active at night], and they have low population density,” Yuma notes. “It is difficult to spot them by eye.” So spotting owl eDNA in the air might be a very efficient way to find them. The teens designed a device that attaches to a tree trunk. It pulls in air and bubbles it through a liquid that collects DNA. Then, Yuma and So could take the solution back to their school and extract any eDNA it had picked up.

The teens tested their design first on white-cheeked starlings. These birds gather in large flocks, which suggested they should shed lots of eDNA. Yuma and So placed their detector in a spot where starlings liked to hang out. As a control — a part of the experiment where they expected no result — they placed their detector on a different day in some spot where starlings were rare. And the teens were able to show their device easily picked up starling eDNA when starlings were hanging around.

They also showed that the eDNA doesn’t last long. It breaks down quickly when exposed to sunlight and air. It also doesn’t travel far. Even when starlings were only 50 meters (164 feet) away from their perching site, their device could not detect them.

So how well did the teens’ system work at detecting owls, which are much rarer in the environment? On 20 times, at 6 different locations, Yuma and So scouted for owl DNA. Each time, they would leave the detector out for 16 hours — plenty of time for an owl or two to fly by. As a control, the students got owl feathers from a local zoo and a museum. By testing those feathers, they knew what DNA they should be looking for. The teens were able to detect two different species — the Ural owl and the brown hawk-owl.

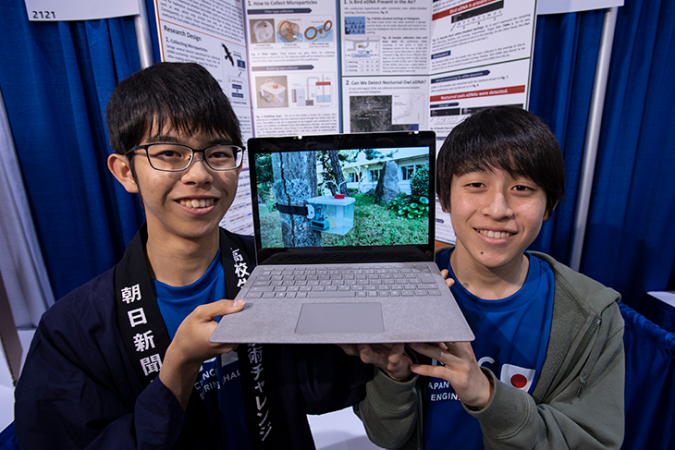

So and Yuma brought their stealthy bird detector to the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. This yearly fair was created in 1950 by Society for Science & the Public, which still runs the event. (The Society also publishes Science News for Students.) This year, the Intel-sponsored fair brought together more than 1,800 students from 80 countries to share their science projects.

“In the future, this method could be applied to a lot of birds,” Yuma says of his new system. “We want to use this method for endangered species,” or species that are shy and hard to spot. The teens also hope to improve their device so scientists can catch birds as they fly by — even if they never see them at all.