Barnyard science: Check out this fowl research

From the chicken to the egg, these teens are bringing science to the farm

Chickens are used for food around the world. Some teens have now studied how best to store eggs, how to use feathers to keep buildings warm and more.

WDnet/iStockPhoto

PITTSBURGH, Pa. — People eat a lot of chicken. In fact, there are more chickens on Earth than any other bird. People around the world rely on chicken and their eggs for protein. And of course, these birds are pretty tasty. But they aren’t just about food. Chickens can also provide the basis for a good science fair project, as four teens showed last month.

An Australian girl tested how best to store eggs so that they remain tasty and healthy. Another pair of teens from Malaysia showed why ground-up eggshells might provide more fire-resistant surfaces. A fourth teen, from Egypt, investigated the insulating potential of chicken feathers.

All four described their projects at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. This competition was created by and run by Society for Science & the Public. It is sponsored by Intel. The fair brings together nearly 1,800 students from 81 countries to share their research. (The Society also publishes Science News for Students and this blog.)

The chicken projects showcased at this year’s Intel ISEF promote safety and find new uses for what might otherwise be wasted. They show how young scientists can use local resources to answer questions and solve problems.

Science on the half-shell

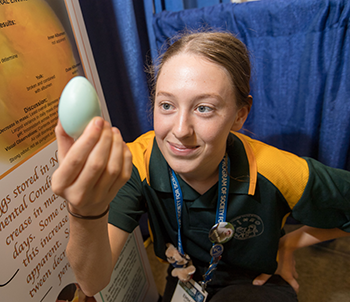

Chickens have always been a part of life for Emma Serisier. “I live on a farm back home in Australia,” explains the 16-year-old junior from Bishop Druitt College in North Boambee Valley, Australia.

The 100 chickens on her family’s farm produce 20 to 30 eggs each day. “There’s a worldwide debate about where to store eggs,” she notes. “Back home in Australia they can be stored on the shelf. Sometimes they’re sold that way.” In contrast, she notes, here in [the United States] all eggs are stored in the fridge.” Why? Farmers wash U.S. eggs to get them clean. But that also wipes off a protective coating — one that prevents germs from getting in. So these now-unprotected eggs must be kept cool to slow the growth of bacteria. In contrast, unwashed eggs can go from the chicken straight to the store, protective coatings intact.

Emma’s family had never worried about a need to keep their stored eggs cold. But did storing them at room temperature compromise their flavor? “I wanted to find out,” the teen says. And with that, a science-fair project was born.

Eggshells are full of holes, known as pores. “Eggs have up to 17,000 pores,” Emma notes. These let oxygen in, and water and carbon dioxide out. The temperature at which eggs are stored might affect how much water and carbon dioxide leave them. And that might change how long the eggs would be safe to eat.

Emma’s Araucana hens lay eggs with light green shells. The teen collected 12 eggs from her hens, then chilled three in the fridge at 5° Celsius (41° Fahrenheit). Three more sat on a shelf at room temperature (24 °C or 75 °F). She stored another three under a heat lamp for two weeks. (“I wanted to mimic eggs in a hot car,” she explains.) The final three eggs sat outdoors, exposed to wind and weather.

Every day for 16 days, Emma measured each egg’s mass. She also put a flashlight up against each. to look at air pockets inside the shells. This offered one gauge of how much water might be entering or leaving each egg. On the last day she cracked each egg open.

Those that had been stored on the shelf or in the fridge only lost about two percent of their mass to evaporation. Their yolks and whites looked fine, just like a healthy (if slightly old) egg. The eggs under the heat lamp, though? “They were so gross. The yolks had coagulated,” Emma says. “I would not eat them!”

The only thing grosser were the eggs that had been stored outside. It had rained on four of the test days, and some of that water slipped through the pores and into the eggs. These had “sort of scrambled. They didn’t have a yolk — it was just a liquid mixture,” she says. And, well, “they smelled like rotten eggs.”

Emma concluded that high temperatures (like a heat lamp) and fluctuating conditions (like sitting outdoors on warm or rainy days) can make eggs suffer. She now concludes that a cool, dry place makes for good eggs — on the shelf or in the fridge.

Firing up the shells

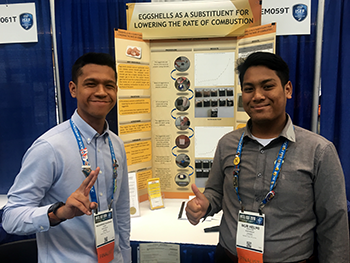

For Emma, what’s inside the shell matters most. In fact, those shells will become trash once a cook cracks one open to make a cake or omelet. Nur Helmi Arwizar and Muhammad Shazwan Sobri, both 17, want to turn that waste into a resource — one to “save lives.”

The two seniors attend MARA Science Junior College in Nibong Tebal, Malaysia. It’s a common thing for us to hear about fires that cause death,” says Helmi. The teens reasoned that powdered eggshells might slow down house fires. Slower fires would give people more time to escape.

But why eggshells? It has to do with their chemistry. Calcium carbonate gives those shells their strength. The same chemical is an ingredient of many rocks, such as limestone. As it burns, calcium carbonate releases carbon dioxide. Being heavier than oxygen, that carbon dioxide stays close to the ground or to some burning surface. This keeps oxygen from fueling the fire. Indeed, that carbon dioxide release should actually slow a fire’s spread. Or that’s what the teens hypothesized.

To test that, Helmi and Shazwan collected the shells of eggs that had been used by their school’s cafeteria. After grinding them into a powder, they mixed the shells into house paint. The teens tried different ratios of shell powder to paint — from 0 to 80 grams (0 to 2.8 ounces) in every 50 milliliters (1.6 ounces) of paint. They used both latex (water-based) and oil-based paints. Then, the pair painted wood blocks with each recipe.

Later, Helmi and Shazwan held the dried blocks close to a flame and measured how long each took to ignite. Those coated with shell-free paints caught fire in about 30 seconds. Paint having the most shell in it didn’t catch fire for more than 6.5 minutes.

Both water- and oil-based shell-treated paints took longer to burn. But the oil-based paint is thicker, Helmi says, so the ground eggshell spread more evenly within it.

“We want to collaborate with a university,” Shazwan says, to refine this product and spread the word of its life-saving potential.

Feather your nest

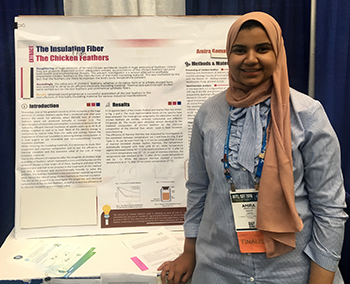

Shells aren’t the only part of a chicken that normally goes to waste. So will its feathers. “Because we consume so many chickens around the world, we have huge amounts of chicken feathers left over,” observes Amira Abdelazim, 17. Some of that gets ground up and fed back to other chickens as feed. The rest will be thrown away or burned. Amira, a junior at El Menia Preparatory Secondary School for Girls in New Menia, Egypt, found a better use for this resource: “as a green organic insulation.”

Insulation is material used to keep heat from moving into or out of buildings. This will help keep people warmer in winter and cooler in summer.

To figure out what chicken feathers are made from, Amira turned to a spectroscope. This device measures light bouncing off of a surface. The colors given off will correspond to the chemicals in it.

The chemical makeup of chicken feathers turned out to be very similar to the fiberglass widely used as insulation today. These data seemed to confirm chicken feathers might make good insulation.

Now came the test. Amira took an insulated metal bottle and replaced its original insulation with ground up chicken feathers. Then she poured in a boiling liquid. She measured its temperature over time to see how quickly it cooled. She did the same thing to the liquid that she poured into a metal bottle with no lining and to one with a vacuum-lined jacket (known to keep liquids very hot for a long time). She checked the temperature inside each bottle after 24 hours.

Liquid in the unlined bottle had cooled to room temperature — 24 °C (75 °F) — by the next day. But the drink in the vacuum-lined bottle was still a toasty 57 °C (134 °F). The chicken-feather insulation allowed the liquid to cool to around 31 °C (87 °F).

Clearly, the chicken feathers didn’t work as well as the vacuum lining. Still, Amira concludes, feathers might find use insulating buildings. They “are much, much cheaper” than conventional building insulation, she notes. “One ton of chicken feathers would cost $8,” she says. An equivalent amount of synthetic fiber, she says, costs $1,200.

Amira isn’t the only researcher looking to use chicken feathers for this purpose. A company in England is working to transform chicken feathers into a range of products — including insulation. Amira has similar goals. She says “I hope to turn my project into a factory to make thermal products from chicken feathers.”