Bats in the attic prompt boys to create a better bat detector

They also developed a citizen science site to log bat calls

This is a common pipistrelle, a bat native to Ireland — and to Dylan Bagnall’s attic.

Barracuda1983/Wikimedia Commons (CC-SA-3.0)

PHOENIX, Ariz. — When Dylan Bagnall, 17, and his family first heard skittering sounds in the attic, they assumed their house had rats. But when the exterminator showed up, everyone was in for a surprise. Dylan’s family was hosting some 700 bats. What to do? Develop a science-fair project to identify their flying housemates — and to help others identify them, too.

Dylan is a junior at The King’s Hospital School in Dublin, Ireland. For help, he turned to fellow student and friend Richard Beattie, 17. “Richard, help me,” he said. “I’ve got 700 bats.”

If he hadn’t been interested before, Richard says, hearing “700 bats” gets you interested. The bats, which are protected in Ireland, had to stay. They cannot be evicted, disturbed or even handled without a license. They eat insects, of course. Bats also pollinate some plants. Ireland has nine bat species, but Dylan had no idea which species was living in his attic. The teens decided to find out.

To start, Richard recalls, “We got a bat detector and went on bat walks with local bat groups.” Bat detectors have a microphone that takes in bat sounds. Those sounds are ultrasonic — too high pitched for a human to hear. So the device “translates” the sounds, playing them back at a frequency people can hear.

But the teens weren’t satisfied with their detector. They couldn’t save the calls they heard. They also couldn’t get a graph of the call — a pictured voiceprint of the call as it was detected. Having one might help identify the bats. Richard and Dylan also were shocked by how expensive bat-call detectors could be. They decided they needed to build a better voice trap for these bats.

Bat boys

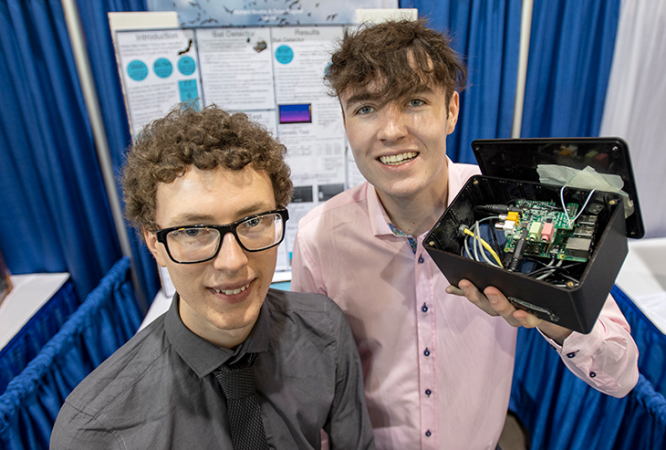

They started with a Raspberry Pi computer and the microphone from a smartphone. Their new device takes in and plays back bat calls, of course. But that’s not all. “We can record the audio, not just listen to it,” Richard says. The system will “show graphs and play it in a form you can hear,” Richard says. And the new detector cost the guys only $137 to make — much less than the cost of standard bat detectors.

Since the teens developed the detector when the bats were hibernating in the winter, they also developed a computer program to act as their test bat. “It generates ultrasonic sounds,” Richard says. And their new detector picked up them all.

It also helped the teens identify the bats in Dylan’s attic.

Some bats have very similar calls. Voice alone wasn’t going to be enough to distinguish between them. So the teens scooped up some bat poop, known as guano. (With 700 bats, that was easy.) They used it to develop a simple DNA test that could pinpoint which of the nine types of Irish bats were living in the attic.

Their investigation confirmed what an ecologist told them: The bats in Dylan’s attic did not all belong to one species. In fact, there were three: Lisler’s bats, common pipistrelles and soprano pipistrelles. “They can all live together because they don’t compete for food,” Dylan explains.

Notes Richard, “There’s lots of people with bat roosts. They may have bats and not know how to identify them,” he says. “We found there was no place for citizen scientists to share this information.” So the teens built a website called Bat Identification. Here, anyone can upload a bat call. Other bat enthusiasts can listen to them and help identify which species made them. In this way, Richard explains, “We can create an accurate map of Ireland’s bat populations to pinpoint where species are as they move.” That should “help conservationists target their efforts” so that they can protect more bats.

The teens brought their bat detector here to the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. Created and run by Society for Science & the Public, the fair was sponsored by Intel this year. The event brought together more 1,800 students from 80 countries. (The Society also publishes Science News for Students.) Dylan and Richard ended up bringing home a $5,000 award for best project in Animal Sciences.

And they’re not done. Because bats are so important to our ecosystem, Dylan says, “We want as many people as we can to identify bats around the world.” The teens used genetics to identify their bats, by species. Now they want to make sure that others can too.

Right now, the teens are trying to work with a university to see if it can help do the DNA tests to identify bat species. That way, someone could upload bats calls and mail in some guano to confirm which species they might be hosting.

Dylan’s family is thinking of moving. How do you sell a house with an attic full of bats? Says Richard: “We’ll just tell [potential buyers] how important bats are.”