Teen’s research suggests spinning wing parts might boost aircraft safety

Whirling device on a wing’s leading edge could help prevent stalls and spins in some situations

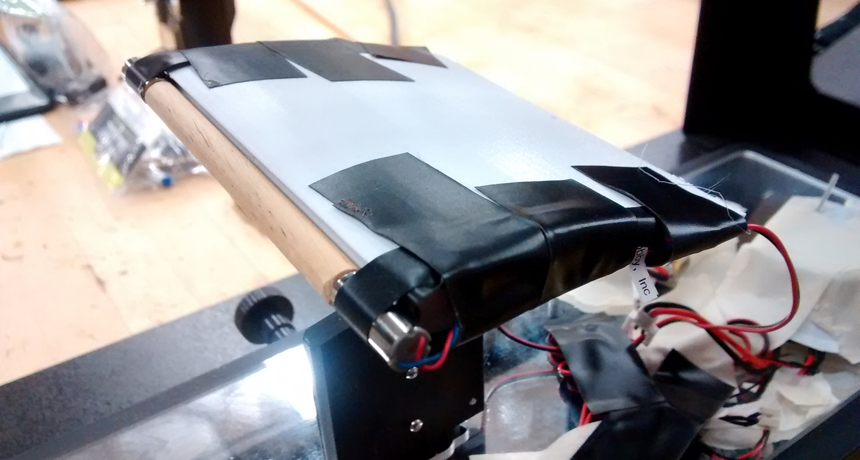

Replacing an aircraft wing’s leading edge with a spinning cylinder could increase lift, reduce drag and help prevent some stalls and spins. That’s the findings of a teen’s new research.

Ian and Rylan Gardner

By Sid Perkins

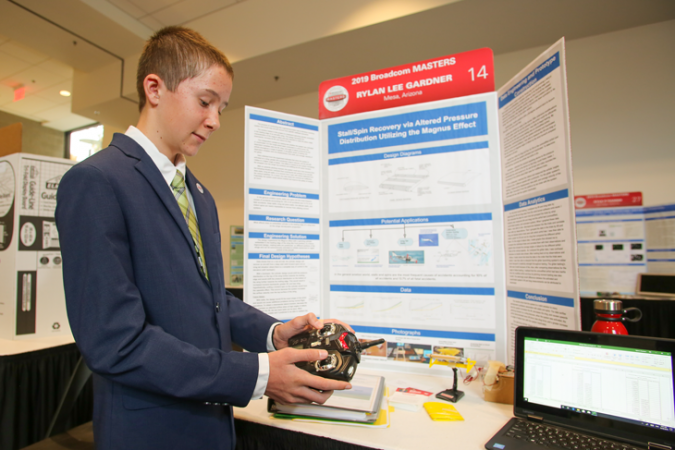

Washington, D.C. — A device that harnesses the same aerodynamic effect that makes a curveball swerve might one day boost aircraft safety. How? Such a device could prevent some aircraft stalls and spins. Such instabilities underlie one in every 10 small-plane accidents in the United States, notes Rylan Gardner.

The 14-year-old lives in Mesa, Ariz., where he attends 9th grade at Franklin Junior High School. He designed such a device as a science fair project.

Air speeds up as it flows over the upper surface of an aircraft’s wing. That faster flow lowers the air pressure. It’s that pressure difference between the upper and lower surfaces of a wing that generates the lift that keeps an aircraft aloft.

But there’s another way to generate lift, he notes. This alternative is known as the Magnus effect. It develops when air flows past a rotating sphere or cylinder, Rylan explains.

On the side of the sphere or cylinder that’s rotating into the wind, the air slows down. Here, air pressure increases. On the side where the surface rotates away from the wind, air speeds up. There, air pressure drops. The difference in pressure between the two sides creates a push against the cylinder or sphere. This generates lift.

Rylan explored this idea in a science fair project last year. That research qualified the teen to compete here, late last month, in the ninth annual Broadcom MASTERS competition.

MASTERS stands for Math, Applied Science, Technology and Engineering for Rising Stars. This program for middle-school researchers was created by Society for Science & the Public (which publishes Science News for Students). The Broadcom Foundation, headquartered in Irvine, Calif., sponsors the event, which brings together 30 finalists each year to tackle team challenges.

Last month, Rylan showcased his Magnus-effect research at the meeting.

Stop stalling!

Aircraft stalls and spins account for not quite one in every eight fatal accidents in small planes, the teen notes. Even experienced pilots can have trouble recovering from such stalls and spins. But replacing the leading edge of an aircraft’s wing with a rotating cylinder might help, he says.

For example, one dangerous event is known as a deep stall. It occurs when the airflow from a plane’s wings washes directly over the plane’s tail. This can render the control surfaces on the tail useless. But if a cylinder embedded in an aircraft’s leading edge were rotating with backspin (where the front of the cylinder constantly rotates upward), that would change where the wing generates lift, Rylan explains. This would create lift farther back than normal on the top of the wing. And on the bottom surface, areas of high pressure that push upward also would shift toward the rear of the wing. Together, those changes would cause the airplane to pitch forward. That, in turn, should cause airflow from the wing to shift off of the aircraft’s tail, ending the deep stall.

“Potentially, this system could reduce crashes and improve the safety of modern air travel,” Rylan says.

Broadcom MASTERS awards first- and second-place prizes in each of the STEM categories. (STEM stands for Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics.) For his qualifying project, Rylan nabbed the first-place award — worth $3,500 — in Engineering.

In most student science competitions, the majority of the finalists’ scores are based on qualifying science-fair projects. That’s different from how it works at Broadcom MASTERS. Here, roughly four-fifths of the finalists’ scores are based on both their creativity and teamwork in helping to solve on-the-spot research challenges.