Fingerprints could help keep kids from dangerous websites

A teen develops a program that estimates age based on someone’s fingers

Everyone’s fingerprint is unique. It also can be used to figure out how old you are, a teen shows.

azerberber/iStockphoto

Pittsburgh, Pa. — As he walked through his school, Paritosh Dahiya, 16, couldn’t help overhearing younger kids talking about what they saw on the internet. And sometimes he was appalled at what he heard. Kids much younger that he were talking about violence and suicide. This got him wondering whether there might be a way to protect kids from harmful online content — before they saw it. He soon hit on an idea: fingerprints.

“Horrible things are out there,” says this senior at DAV Multipurpose Public School in Sonipat, India. ”It kind of baffles me that kids are not protected online.”

The tiny ridges and whorls on our fingers are our own unique IDs. “Fingerprints denote more uniqueness than any other feature,” Paritosh says. “Two people can have similar facial features, but no two people — even identical twins — have the same fingerprint.”

What’s more, the pattern in a fingerprint never changes. Over time, as people age, the spaces between each tiny ridge become slightly wider. As people grow up, their fingerprints spread out. Paritosh suspected that he could figure out how old someone was based on how far apart those ridges had become. But first, he was going to need some fingerprints. A lot of them.

There are many fingerprint databases, “but none of them are classified according to age,” he says. Time to go fingerprint hunting.

The teen asked people in parks and schools to sign consent forms. He then used a device called an optical scanner to create images of people’s fingerprints. More than three months, 650 people and 3,200 fingerprints later, Paritosh had his own database. It resulted in a lot of consent forms— “3 kilograms [6.6 pounds] of paper,” he says. But it was worth it; this one did classify fingerprints by someone’s age.

The teen then took his database to Ritesh Vyas. He studies biometrics — how to identify people based on their features. Vyas works at the National Institute of Technology in New Delhi, India. Under his mentoring, Paritosh learned how to take a group of fingerprints and use them to estimate someone’s age.

First, Paritosh grouped his database into age ranges. One group was kids aged five to 14. The second was teens aged 14 to 18. The last group had people 18 and older. The teen then developed a computer program that compared a new fingerprint to those already stored in his collection. It matched the size of the space between fingerprint ridges to those of people in a particular age range. This allowed him to estimate the age of the person who had provided the new fingerprint.

And that program was accurate 88.6 percent of the time, he now reports.

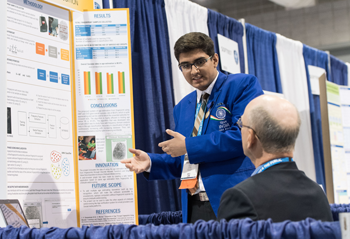

The teen presented his results, here, earlier this month at the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). Created by Society for Science & the Public, this year’s fair is sponsored by Intel. The yearly competition brings together almost 1,800 teens from around the world to present their science-fair projects. (The Society also publishes Science News for Students and this blog.)

Paritosh says his system for identifying a child’s age could be used very quickly. “Many companies have started making laptops already embedded with a [fingerprint] scanner,” he notes. He will be making his program freely available to all.

He’d like to also enhance his project. Instead of just fingerprints, it might identify people based on their faces. That could make his new application much more powerful, he says. “Many computers or old smartphones don’t have fingerprint scanners, but they all have a web camera or front-facing camera.” By keeping computers secure, he hopes to protect kids around him from the worst the internet has to offer.