A robotic fish could help mangroves grow

The mudskipper mimic measures mud

This is a giant mudskipper. Two teens built a mudskipper robot to find the right kind of mud for growing mangrove trees.

Bernard DUPONT/Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA-2.0); adapted by L. Steenblik Hwang

PITTSBURGH, Pa. — Mangrove forests are important ecosystems. Their tangled roots hold land in place, preventing the sea from washing it away. Those roots also shelter young fish and other animals as they grow. But the mangrove forests of Thailand have come under threat. People have cut many of them down to build fish farms and expand cities. Some efforts to regrow mangrove forests have been successful; others, not so much. Naphat Cheenchamrat, 18, and Pattharaphol Chainiwattana, 16, wanted to figure out why. For mangroves, mud matters. And to find out if mud is thick enough to plant new mangroves, the pair have just what everyone needs: a fish robot.

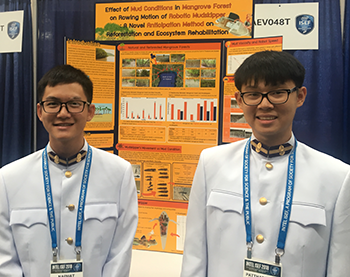

Naphat is a senior and Pattharaphol a junior at Bangkok Christian College in Thailand. The two brought their muddy results here, to the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF). They joined nearly 1,800 students from 81 countries in presenting their winning science fair projects. This fair was created, and is run, by Society for Science & the Public. This year, it is sponsored by Intel. (The Society also publishes Science News for Students and this blog.)

“Nowadays, there are a lot of campaigns to regrow mangrove forests,” Naphat explains. But some of the reforested areas just don’t seem to do very well. Naphat and Pattharaphol began to notice one big difference between healthy, natural mangrove forests and the reforested, weak-looking ones. Mudskippers.

Mudskippers are fish. But they stick to the fishy lifestyle only part of the time. These creatures move back and forth between land and water. They live in mud burrows and breathe air through their skin. They hop along the mud, their stiff front fins making a rowing motion. They can even jump and climb on the exposed roots in the mangrove forests they call home.

In natural mangrove forests, Naphat and Pattharaphol noticed there were plenty of mudskippers. But in the reforested areas, the mudskipper population was very thin. Since mudskippers need mud for their burrows, the teens wondered if thick mud could be what mudskippers — and mangroves — needed.

This is where the robotic fish comes in. “We used a robot because [we] didn’t want to disturb the real mudskippers,” Naphat explains. And hey, it’s always fun to build a robot. The students created a fish-sized robot. It skipped forward using rowing motions from its fins — similar to the motions of a real mudskipper.

Then, the teens collected mud from natural and reforested mangrove forests. They placed their robot on the different surfaces and measured how fast it could move. In the mud of a natural mangrove forest, the robot skipped along at around 8 centimeters (3 inches) per second. But in the mud of a reforested mangrove forest, the robot struggled. It crept at only 3 centimeters (1.1 inches) per second.

Those measurements allowed Naphat and Pattharaphol to calculate the viscosity of the mud in which the robot traveled. Viscosity is a measure of how thick a fluid is. Thick mud allows mudskippers to travel quickly over the muddy surface and build strong burrows below. Thinner mud leaves the mudskippers (or the mudskipper robot) wallowing in the mess.

The natural mangrove forests had that thick, viscous mud, the students showed. Reforested mangrove forests, in contrast, are often full of thinner mud. Unfortunately, reforestation efforts focus on planting on thinner mud because it’s mud that people don’t want to build on. “They are planting where the mud isn’t good enough,” Naphat says. “In mud with lower viscosity, the mangrove trees don’t survive.” After presenting their work at ISEF, the American Statistical Association awarded the pair an honorable mention.

Naphat and Pattharaphol want to use their mud studies and robot to help pinpoint the best spots to plant mangroves. They have already begun testing their robot in different muddy areas, to show which ones are best for mangrove trees — and the real mudskippers.