Snot Science: Stopping the sneeze

How well does a tissue help stop a spew of snot?

We’ve all been told to cover our noses when we sneeze. But how well does it stop snot spread?

AnneMS/iStockphoto

This article is one of a series of Experiments meant to teach students about how science is done, from generating a hypothesis to designing an experiment to analyzing the results with statistics. You can repeat the steps here and compare your results — or use this as inspiration to design your own experiment.

Cold and flu season mean that sneezing and runny noses are everywhere you look. Standing far away might seem like protection from infection. But you have to step pretty far back. Some scientific studies have shown that droplets from a sneeze can fly up to eight meters (26 feet)! If you’re lucky, the sneezer will have a tissue handy. But does sneezing into a tissue really stop the snot? Science has the answer.

SSP/Explainr

In my very first DIY Science video, I asked how far a sneeze could travel and whether thick or thin snot traveled the farthest. I found that thin snot (using colored water as a stand-in, no real boogers involved) shot an average of three meters (9.8 feet). Thick snot (gelatin and corn syrup) only sprayed about a meter (3.3 feet).

If people are polite, though, they usually don’t just let a sneeze fly free. There’s an elbow or a hand in the way. If they’re very well prepared, they might have a tissue at the ready.

But tissues are flimsy, soft sheets of paper. Can something that tears so easily stop a virus in its tracks? To find out, I need to do another experiment.

Snotty studies

I’ll start with a hypothesis — a statement that I can test. I hypothesize that a tissue in front a sneeze will make snot fly a shorter distance than a free sneeze.

Instead of tickling the noses of a bunch of people to make them sneeze, I’m using a model of a sneeze. I filled a dropper with one milliliter of colored water. Then I squirted the dropper for my “sneeze.” To measure how far my “snot” flew, I used a plastic tarp marked every half meter (50 centimeters, or 20 inches).

Ideally, to detect a large difference I would repeat the experiment 26 times. Unfortunately, reality intervened, and I only had time for 12 repetitions of each sneeze type, tissue and no tissue.

Each time I squirted the dropper, I wrote down how far the farthest drop flew. That gave me the maximum distance for the sneeze. I also counted how many drops landed in each half-meter segment of tarp. That would tell me where the sneeze concentrated.

Booger blockade

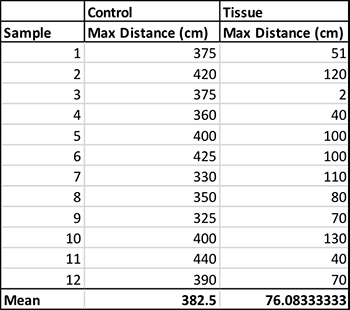

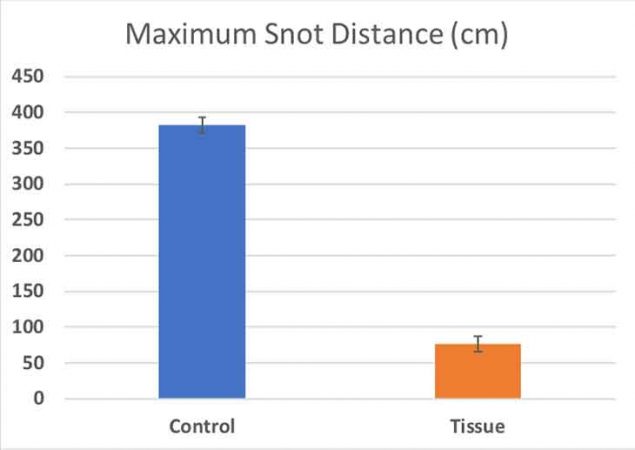

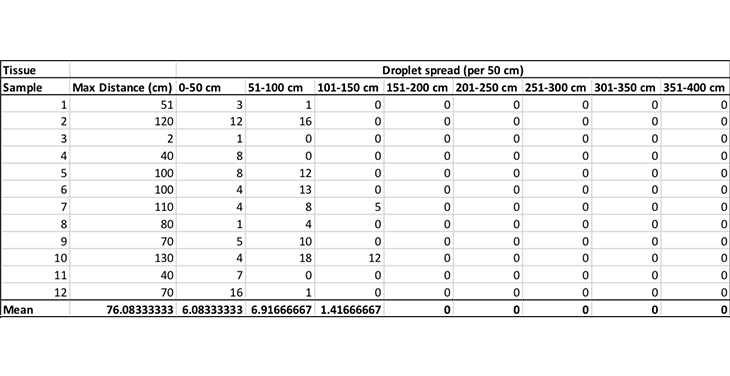

The spreadsheet shows the maximum distance the sneezes flew, with and without a tissue. At the bottom I’ve calculated the mean — the average total distance — for each condition. For my no-tissue control, my sneezes spread a mean of 382 centimeters (150 inches), a little farther than in my previous study. With the tissue, the snot flew an average of 76 centimeters (29 inches).

These numbers seem very different, but to be sure, I need to do some statistics — tests to analyze data and interpret their meaning. In this case, I used a t test — a test used to find the differences between groups. I will be looking for two numbers. The first is a p value. This is a probability measure — or how likely it is that I would have found by accident a difference as big as the one I saw. Many scientists consider a p value of less than 0.05 (or a five percent chance) as statistically significant. There are lots of free sites that will do these calculations. I used this one.

The calculator told me that the p value for my data was 0.0001. That’s a 0.01 percent chance that this difference happened by accident. However, this doesn’t tell me how big the difference is in my data. To find that, I looked for a measure called Cohen’s d. I will need a standard deviation for this — a measure of how much the data spread around my means. You can find out more about that in one of my previous posts. I plugged the means, standard deviations and number of samples into this calculator.

My Cohen’s d value was 8.2. Generally, scientists define a Cohen’s d below 0.2 as a small effect size and above 0.8 as a large one. So this Cohen’s d is gigantic. A tissue, it turns out, makes a big difference.

Snot spread

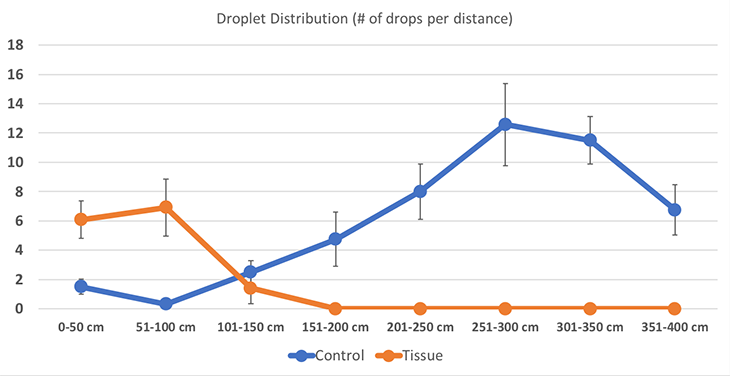

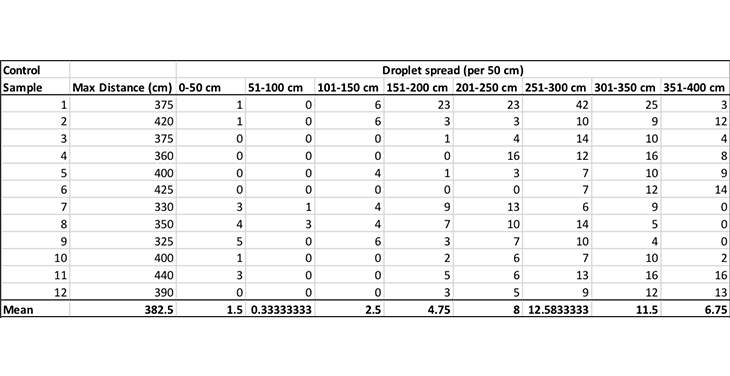

The snot did not make it as far with a tissue as without. It also changed how the snot concentrated along the flight path. Below is the data for how many droplets fell per 50 cm (20 in) of tarp. I then took that data and created a graph to show what the two groups look like when compared to each other.

You can see that without a tissue, the snot droplets concentrate farther out, between 200 and 400 cm (79 and 157 in). With the tissue present, snot droplets concentrate much closer to the sneezer.

Of course, this isn’t a perfect study. I could run more trials, or I could use real noses with real sneezes. But this experiment still helped me test my hypothesis. I hypothesized that a tissue in front a sneeze will make snot fly a shorter distance than a free sneeze. My results appear to support my hypothesis. A tissue in front of a sneeze shortened the snot range.

So the next time someone sneezes and doesn’t cover their mouth, hand them a tissue. You’ve got science on your side.