Some teens perform better when they multitask

Two high school students did a study to measure how well teens multitask

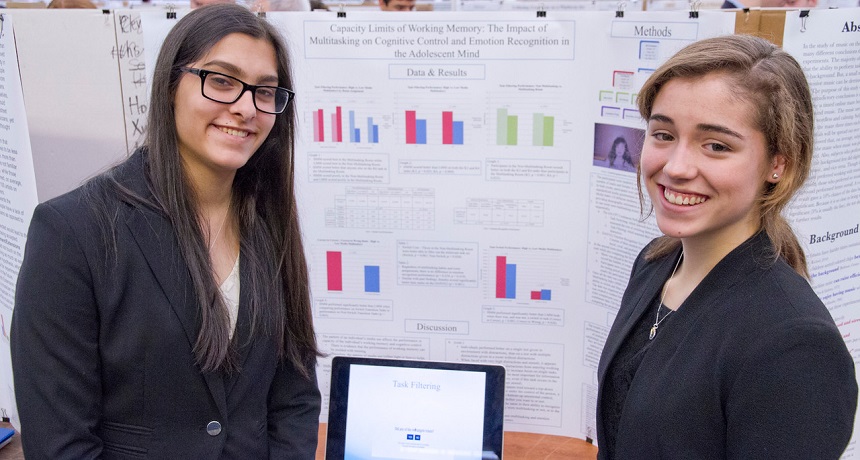

Sarayu Caulfield, left, and Alexandra Ulmer, right, showed that some teens perform better when multitasking.

Tom Berridge/Oregon Episcopal School

Whether doing homework or taking notes, we’ve always been told to drop our phones and pay attention. And for most people, that’s good advice. But two teens now report finding that for certain people in the digital generation, dropping everything to focus might hurt more than it helps. Sarayu Caulfied, 17, and Alexandra Ulmer, 18, presented their findings at a scientific meeting on October 11.

“Even in school we have our phones or computers on all the time,” says Sarayu. “We wanted to see how that might affect our ability to multitask.” Most studies in adults show that tackling multiple tasks at once — such as answering texts and email while watching TV, for example — makes it harder to effectively focus on each task and perform accurately.

But what about teens? Most have grown up with the Internet no more than the click of a button away. “Media is a massive part of our lives,” Alexandra explains. “We’re seeing people flipping back and forth between tasks all the time. They might take notes and answer questions in class and be on Facebook at the same time.” She and Sarayu, both students at Oregon Episcopal School in Portland, Ore., decided to study teens and multitasking for a research project. They have just presented their results at the American Academy of Pediatrics national meeting in San Diego, Calif.

The two recruited more than 400 middle- and high-school students at their school. All filled out a questionnaire about how much they multitasked each day. Then each participant had to perform two tasks that helped assess how well they process information.

The first test measured their ability to answer questions accurately while focusing on a task. The second measured that accuracy in answering questions when they had to switch back and forth from one task to another.

During their tests, participants sat in one of two rooms. The first was kept quiet. The other was full of distractions, with music playing and email coming in. In this room, students were forced to multitask: While they took their tests, they also had to count all of the songs that played and respond to emails.

“Most people performed best when focusing on just one task,” Alexandra says. “But we had a very small group of people who were high media multitaskers. They performed best in the multitasking room, where there was distraction and multiple tasks.” These were people who had reported that they typically do many things at once — such as answer texts, hang out on Facebook and watch TV — for more than three hours each day.

Most adults were brought up without the Internet or smartphones. They only started using such devices heavily when they were older. Today’s teens, on the other hand, are digital natives — people who have grown up using the Internet and digital technology. This might make them better able to face the modern multitasking world, Sarayu says. “We’ve grown up with media our entire lives,” she explains. “We might be able to cope with it better.”

But both Sarayu and Alexandra caution that this doesn’t mean all teens multitask well. Alexandra suspects that “it’s all about what you’re used to.” She also notes that “our study only focused on two specific tasks.” So their findings might not apply to working on homework or taking classroom exams.

The teens first presented their data at the 2014 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair in Los Angeles, Calif. They found out about the American Academy of Pediatrics meeting through Sarayu’s mother, a pediatrician. “We wanted to share our research with the world,” Sarayu says. “So we thought, why not go for it.”

Both teens have enjoyed doing research since middle school. Both hope to continue doing research in college. The most important thing about picking a project, Sarayu says, is to “choose what you love to do. It makes the process so much more fun.”

She recalls a night when she and Alexandra were hanging out. They were analyzing their data while eating Thai food. “We got a really cool result, and we suddenly realized ‘this is what we do research for.’” The teens are currently expanding their study to include adults, and plan to publish their findings in a peer-reviewed research journal.

Follow Eureka! Lab on Twitter

Power Words

adolescence A transitional stage of physical and psychological development that begins at the onset of puberty, typically between the ages of 11 and 13, and ends with adulthood.

digital (in anatomy) Relating to the body’s digits — fingers or toes. (in computer science and engineering) An adjective indicating that something has been developed numerically on a computer or some other electronic device, based on a binary system (where all numbers are displayed using a series of only zeros and ones).

digital data The type recorded and stored as a series of ones and zeros.

digital information The type recorded and stored as a series of ones and zeros.

digital native A person who was born after digital technologies such as the internet and smartphones were introduced and who has used these technologies from an early age. They often have more comfort using digital technologies than those who were brought up before the wide introduction of the internet.

digitize To convert data, often pictures or sound into a numerical form that can be processed by a computer.

media (in the social sciences) A term for the ways information is delivered and shared within a society. It encompasses not only the traditional media — newspapers, magazines, radio and television — but also Internet- and smartphone-based outlets, such as blogs, Twitter, Facebook and more. The newer, digital media are sometimes referred to as social media.

multitask To perform more than one task at a time. Computers often do this. People can too, such as when they listen during a meeting and take notes at the same time.

pediatrics Relating to children and especially child health.

peer review (in science) A process in which scientists in a field carefully read and critique the work of their peers before it is published in a scientific journal. Peer review helps to prevent sloppy science and bad mistakes from being published.

questionnaire A list of identical questions administered to a group of people to collect related information on each of them. The questions may be delivered by voice, online or in writing. Questionnaires may elicit opinions, health information (like sleep times, weight or items in the last day’s meals), descriptions of daily habits (how much exercise you get or how much TV do you watch) and demographic data (such as age, ethnic background, income and political affiliation).