Women in ecology, from forests to the sea

These women in science are all about ecosystems and environments

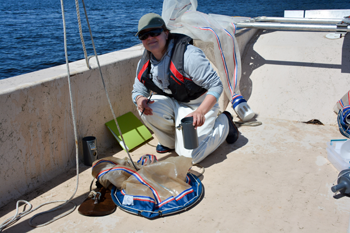

Marah Hardt wants to make seafood sustainable.

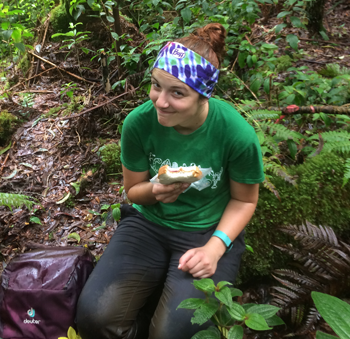

Jo Laughlin, Big Island, Hawaii.

When Science News for Students decided to have a feature story on women in science, technology, engineering and math, we put out a call for women in STEM to send us their images and videos. We wanted to show our readers what scientists are really like.

We ended up with more than 150 responses from 18 countries! And we decided to share them all here on Eureka! Lab.

Today, we celebrate women in STEM studying the seas, investigating insects, fighting pollution and finding out how the living things in our world work together.

Bethanie Carney Almroth

People create a lot of pollution and trash in their day-to-day lives. A lot of it goes into the oceans. What does it do to the animals living there? Carney Almroth wants to find out. She’s an ecotoxicologist at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. An ecotoxicologist is someone who studies the effects of toxic substances on organisms and the ecosystems in which they live. “I study the effects of environmental stressors on marine and aquatic organisms,” she says. “This includes pollution, endocrine disruptors and microplastics.” But Carney Almroth doesn’t just do research. She also works hard to educate the public about where their trash goes and the harms it can have.

Carney Almroth likes to fill her life with living things. Not only does she have three children, she says, but “I also have two dogs, two parakeets, a bearded dragon, cichlids — and I love riding!”

Ryan Champiny

Champiny is a forestry technician at North Carolina State University in Raleigh. “My interest is in the interactions between human and natural systems,” she says. “My studies have taken me from the reefs of the Caribbean to the volcanoes of the Galápagos and into the north woods of Wisconsin.”

She’s been into science all her life, even when it got her in trouble. “When I was in kindergarten,” she remembers, “I was sent to the principal’s office because I dug up the playground in search of dinosaur bones.”

Kendall Conroy

You might be reading this on a high-tech smartphone, but people still rely on trees and their wood for a lot of things. Wood is used in everything from paper to building material. But trees don’t grow very quickly. So Conroy studies how we can use them more efficiently. She’s a student at Oregon State University in Corvallis. There she is studying wood science and engineering.

But that’s not all. “Over the last two years I have taken time outside of classes to research the impacts of gender diversity in forestry, which is a very male-dominated field,” she says. Conroy doesn’t just want to study the forests, she wants to see more women out there with her.

Marah Hardt

Hardt took her passion for the ocean out of the lab. She’s the research director for Future of Fish. This is a group dedicated to creating a seafood industry that’s sustainable — providing people with fish while keeping fish populations stable. She also wrote a book, Sex in the Sea, about the different ways ocean organisms mate. “I like to think of myself as a hybrid thinker,” she says. “Combining my science brain with a bit of wild imagination to solve the problems threatening oceans and the people that depend on them.”

Hardt loves science so much, she says, she skipped her high school prom to track sharks. She still says it’s the best decision she ever made.

Brittany Huhmann

In Bangladesh, much of the groundwater is tainted with arsenic, a poisonous metal. That water gets used to irrigate rice fields. Huhmann is a graduate student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. She is working in Bangladesh to try to understand how that tainted water affects rice. She also works with politicians to find better ways of testing for arsenic and keeping this contaminant away from people.

Outside of work, Huhmann loves solving dance puzzles. “I have a really obscure, geeky and super fun hobby: challenge-level square dancing,” she says. “The caller calls fast, complicated sequences built from the 1,000 [or more] calls that the dancers know and combining those calls with challenging concepts, including the use of ‘phantom’ dancers. The dancers work together to follow the caller’s instructions without allowing the square to break down.”

Listen to Huhmann describe her work in the audio clip below.

Ambika Kamath

“I’m a biologist — a behavioral ecologist to be precise — and I study movement patterns and social interactions in lizards,” Kanath explains. She’s in graduate school at Harvard University in Cambridge, Mass. When she goes into the field to study her species, she tags each tiny lizard with three colored beads, so that she can identify them later.

Kanath loves science so much she’s put it on her skin “I have five tattoos — only 2.5 are biology-themed,” she says. “But my first tattoo was of my first study organism.” That would be the larva of an insect called an antlion.

Deborah Lichti

All animals need to eat, even the ones in the ocean. Lichti is a graduate student at East Carolina University in Greenville, N.C. She studies marine food webs. She’s also looking into how nutrients that human activities can send into them might change who’s eating what. Those polluting nutrients include the nitrogen that might run off of farm fields following storms.

Outside of the lab, she says, “I love the arts, especially musical theater, painting and ballroom dance.”

Caitlin Maloney

Did you know that bugs like salty foods? Maloney does! She’s a graduate student at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. And she’s all about insects. “My work focuses on how bugs in the soil of forests in northern Michigan are affected by nutrients such as calcium and sodium,” she says. “Believe it or not, they like salty foods just as much as we do.”

Before she got into ecology, Maloney spent some time with other animals — serving them up for dinner. “I grew up in Maine and spent three years selling lobsters,” she says. “If you ever visited a lobster pound near Acadia National Park, I might have served you a lobster.”

Audrey Maran

“This is what a scientist looks like…while collecting several gallon bags of dying mayflies,” says Maran of the image she sent us. This graduate student at Bowling Green State University wants to make mayflies useful.

“Mayflies spend most of their life in the water but emerge as adults to spend one wild night mating before they die,” she says. “Once they die, people view them as a nuisance because they die in large numbers.” Their carcasses form piles that smell and make roads slippery. “I am studying how we could use these dead mayflies as a supplemental fertilizer source on farm fields,” she says.

Chandreyee Mitra

Science takes researchers to unexpected places. It’s taken Mitra, a biologist at North Central College in Naperville, Ill., to a cemetery. She doesn’t study the dead. Instead, Mitra studies how crickets and butterflies mate and move. But collecting her insects means Mitra has ended up in a spooky space. “My current major specimen collection site is a cemetery, where my students and I work late into the night,” she says. So far, no one’s been too haunted.

Karen Munroe

Munroe’s work involves stuffing (live) squirrels into bags. Don’t worry, she’s only weighing them. “Actually, they don’t mind it that much,” she says. Munroe is an ecologist at Baldwin Wallace University in Berea, Ohio. “I study the social behaviors and mating systems of tree squirrels,” she explains. Weighing them is part of that research. But Munroe also has an artistic past. She studied ballet for 12 years.

Cari Ritzenthaler

Dead things don’t stay around forever, and decomposing insects are part of the reason why. They eat and break down dead material. Ritzenthaler studies these insects as a graduate student at Bowling Green State University. She studies how nutrient availability in soil and leaf litter can affect the abundance and activity of the bugs that take care of the world’s trash.

“I had the opportunity to conduct my research in Hawaii,” she says. In addition to doing a lot of research there, “I visited my first national park, snorkeled with giant manta rays and saw active lava flowing into the ocean!”

Cheree Smith

Do you know where the fish you buy comes from? Smith does. She’s a fishing observer — someone who monitors fishing boats to keep track of what they catch. This can help to make sure that populations of fish don’t fall too low. Or it can check that fishing boats are not accidentally catching endangered species.

Smith’s work has taken her from sea to shining sea. “I started as an observer on tuna boats in Hawaii and Louisiana, then shrimp and reef-fish boats in the Gulf of Mexico,” she says. “I worked as the protected-species trainer for the Pacific Island Observer Program, a marine-mammal observer in Alaska monitoring the salmon-driftnet fisheries.” Now she works as the port coordinator for the Hawaii Observer Program. The program inspects fishing vessels to ensure they are safe for the observers to work from so that they can keep monitoring the fish.

Amanda Winters

Animals in forests live both on the ground and in the trees — and those tree-living species can affect the ground even if they never touch it. Winters, an ecologist at Bowling Green State University, studies how tree-dweller affect the floor far below. “I study bugs,” she says. She’s looking into how herbivores and predators in canopies affect what drops to the forest floor. This material is called “litterfall.” Winters wants to know how it might affect rates of decomposition.

Winters loves bugs so much that she even uses them in art. “My current project is a wedding present for a friend who also really likes bugs,” she says. “I make mutant insects out of different bug parts and put insects in different scenes, like at a party.” She also makes stencils of the bugs she finds beautiful.

If you enjoyed this post, we’ve got more in the series. Make sure to check out our posts on women in astronomy, biology, chemistry and medicine! And make sure to keep an eye out as we show off women in technology, paleontology, neuroscience and more.

Follow Eureka! Lab on Twitter