Hair detectives

Scientists have found a way to figure out where a person is from and where he or she has been, just by looking at samples of the person's hair.

By Emily Sohn

You can tell a lot about people by looking at their hair—and not just whether they brush, spray, or blow-dry.

Scientists have found a way to use hair to figure out where a person is from and where that person has been. The finding could help solve crimes, among other useful applications.

Water is central to the new technique. The liquid makes up more than half an adult human’s body weight. Our bodies break water down into its parts—hydrogen and oxygen. Atoms of these two elements end up in our tissues, fingernails, and hair.

|

|

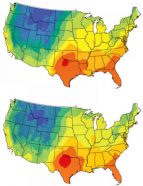

These maps illustrate how the concentrations of certain hydrogen isotopes (top) and oxygen isotopes (bottom) in water differ throughout the United States. Red areas are where concentrations of these isotopes are highest. Blue points to regions having the lowest concentrations.

|

| Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |

But not all water is the same. Hydrogen and oxygen atoms can vary in how much they weigh. Different forms of a single element are called isotopes. And depending on where you live, tap water contains unique proportions of the heavier and lighter isotopes of hydrogen and oxygen.

Might hair record these watery quirks? That’s what James R. Ehleringer, an environmental chemist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, wondered.

To find out, he and his colleagues collected hair from barbers and hair stylists in 65 cities in 18 states across the United States. The researchers assumed that the hair they collected came from people who lived in the area.

Even though people drink a lot of bottled water these days, the scientists found that hair overwhelmingly reflected the concentrations of hydrogen and oxygen isotopes in local tap water. That’s probably because people usually cook their food in the local water. What’s more, most of the other liquids we drink—including milk and soft drinks—contain large amounts of water that also come from sources within their region.

Scientists already knew how the composition of water varies throughout the country. Ehleringer and colleagues combined that information with their results to predict the composition of hair in people from different regions.

The new technique can’t point to exactly where a person is from, because similar types of water appear in different regions that span a broad area. But authorities can now use the information to analyze hair samples from criminals or crime victims and narrow their search for clues.

“This [technique] doesn’t allow you to find the needle in a haystack, but it reduces the size of the haystack,” says Wolfram Meier-Augenstein, an analytical chemist at Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland.

For example, one hair sample used in Ehleringer’s study came from a man who had recently moved from Beijing, China, to Salt Lake City. As his hair grew, it reflected his change in location.

Based on the finding, Jurian A. Hoogewerff, a chemist at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, offers this advice: “If you’re a criminal, shave.”

Going Deeper:

Perkins, Sid. 2008. Hairy forensics: Isotopes can identify the regions where a person may have lived. Science News 173(March 1):131. Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20080301/fob1.asp .