Mice sense each other’s fear

Scientists have figured out how mice use their noses to sniff out fear in other mice.

By Emily Sohn

People can usually tell when others are afraid just by the look on their faces. Mice can tell when other mice are afraid too. But instead of using their beady little eyes to detect fear in their fellows, they use their pink little noses.

|

|

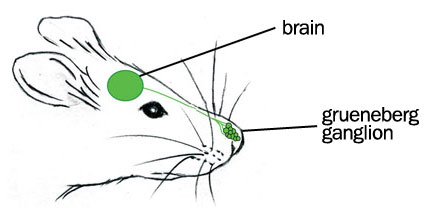

FEAR-OMONE: Mice smell fear in other mice using a structure called the Grueneberg ganglion. The ganglion has about 500 nerve cells that carry messages between a mouse’s nose and brain.

|

| Science/AAAS |

Scientists are beginning to understand how mice sense fear. According to a new study, the animals use a structure which sits inside the tip of their whiskered noses. This Grueneberg ganglion is made up of about 500 specialized cells – neurons – that carry messages between the body and the brain.

Researchers discovered this ganglion in 1973. Since then, they have been trying to figure out what it does.

“It’s … something the field has been waiting for, to know what these cells are doing,” says Minghong Ma, a neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine in Philadelphia, Pa.

Researchers already knew that this structure sends messages to the part of the brain that figures out how things smell. But there are other structures in a mouse’s nose that pick up odors. So, this ganglion’s true function remained a mystery.

To investigate further, researchers from Switzerland began testing the ganglion’s response to a variety of odors and other things, including urine, temperature, pressure, acidity, breastmilk and message-carrying chemicals called pheromones. The ganglion ignored everything the team threw at it. That only deepened the mystery of what the ganglion was actually doing.

Next, the scientists used highly detailed microscopes (called electron microscopes) to analyze the ganglion in fine detail. Based on what they saw, the Swiss scientists began to suspect that the structure detects a certain kind of pheromone – one that mice release when they’re afraid or in danger. These substances are called alarm pheromones.

To test their theory, the researchers collected alarm chemicals from mice that had encountered a poison – carbon dioxide – and were now dying Then, the scientists exposed living mice to these chemical warning signals. The results were revealing.

Cells in the Grueneberg ganglions of the living mice became active, for one thing. At the same time, these mice began acting fearful: They ran away from a tray of water that contained alarm pheromones and froze in the corner.

The researchers conducted the same experiment with mice whose Grueneberg ganglions had been surgically removed. When exposed to alarm pheromones, these mice continued exploring as usual. Without the ganglion, they couldn’t smell fear. Their sense of smell wasn’t completely ruined, however. Tests showed that they were able to smell a hidden Oreo cookie.

Not all experts are convinced that the Grueneberg ganglion detects alarm pheromones, or that there is even such a thing as an alarm pheromone.

What’s clear, however, is that mice do have a much more fine-tuned ability to sense chemicals in the air than do humans. When people are afraid, they usually yell or wave for help. If humans were more like mice, imagine how scary it might be just to inhale the air in an amusement park!