Deadly new virus emerges

A mysterious infection has been spreading for almost a year

By Janet Raloff

Over the past year, a viral infection has infected 15 people — killing nine. All lived in the Middle East or Britain. The novel germ doe not yet have a formal name. It causes pneumonia, a type of severe lung infection. On Feb. 27, scientists from around the world met in Washington, D.C., to share what they know about the mystery illness and its threat.

There is no evidence the disease spreads easily from person to person, reported Gwen Stephens of the Saudi Arabia Ministry of Health in Riyadh. The new virus lives in people’s lungs, throats and noses. Doctors think it probably spreads in droplets of mucus and saliva.

Only a couple of people are known to have caught the virus from someone else. They likely picked up their infection by touching something onto which another sick person had coughed or sneezed. No one knows how everyone else acquired the new germ or how many have been infected. In some cases, the disease may cause symptoms that are mistaken for flu.

A 60-year-old man in Saudi Arabia was the germ’s first known victim. He was hospitalized with a severe lung infection. At first, doctors couldn’t identify its source. So one of the doctors, Ali Mohamed Zaki, isolated germs from the patient and sent them to a virologist in the Netherlands. That expert reported back to Zaki that the bug was a coronavirus. That puts it in the same family as the virus causing severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, Zaki told Tina Saey of Science News.

SARS first showed up in 2002. It also caused a killer pneumonia. Unlike the new virus, SARS spread quickly through the air. It ultimately sickened about 8,100 people around the world.

Despite that difference, Zaki recalls of the new germ, “When I saw it was a coronavirus, I said: ‘This is something dangerous.’”

There is no cure for coronavirus infections, Eric Snijder notes. Snijder is a virologist who works at Leiden University Medical Center in the Netherlands. Doctors can only make infected patients comfortable and hope that their bodies are strong enough to fight the infection.

Meanwhile, Snijder told Science News that his team is investigating how the new germ reproduces. The researchers hope their findings might one day point to a way drugs might be used to interfere with that process.

This break-out infection “is a cause for concern, but not alarm,” Susan Gerber told Science News. Gerber is an epidemiologist with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in Atlanta, Ga. Epidemiologists are like health detectives. They figure out what causes a particular illness and how the disease spreads.

Although the new virus is related to SARS, it infects cells differently and doesn’t spread as easily. But that could change. Viruses can quickly mutate, which means genetically change. One or more mutations could turn a mildly infectious germ into one that can trigger an epidemic. An epidemic occurs when an infectious disease spreads quickly through a community. The big concern is that the new disease might spread like wildfire across the globe, creating what is called a pandemic.

For now, microbiologists (researchers who study microscopic germs) are starting tests to learn more about how the new virus behaves.

For instance, Vincent Munster, who works at a National Institutes of Health virus lab in Hamilton, Mont., has introduced the new germ to animals. Mice and ferrets did not pick up an infection. The virus did sicken rhesus monkeys. It not only damaged their lungs but also caused fever, chills and a loss of appetite.

Munster’s team is now probing what genes the virus affects. Their monkey data indicate the infection alters the activity of more than 170 genes. Many are known to play a role fighting infections or in promoting inflammation. (Inflammation is one way the immune system attacks germs.)

What the biologists learn could help in developing treatments for the new infection — or even a vaccine to prevent infection in the first place.

Power Words

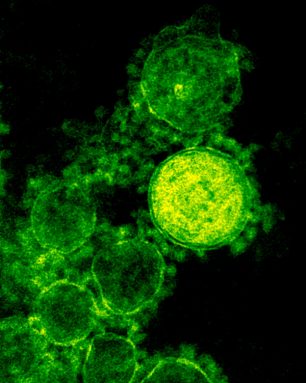

coronavirus A family of viruses named for the crown-like spikes on their surface (corona means “crown” in Latin). Coronaviruses cause the common cold. The family also includes viruses that cause far more serious infections, including SARS and a new unnamed illness.

antibodies Any of a large number of proteins that the body produces as part of its immune response. Antibodies neutralize, tag or destroy viruses, bacteria and other foreign substances in the blood.

epidemic A widespread outbreak of an infectious disease that sickens many people in a community at the same time.

inflammation An immune system response to injury or infection. White blood cells flock to the site. The cells gobble microbes and release chemicals to fight the infection. But the chemicals can cause heat, redness, swelling and pain.

mutation Some change that occurs to a gene in an organism’s DNA. Some mutations occur naturally. Others can be triggered by outside factors, such as pollution, radiation, medicines or something in the diet.

microbiologist Scientists who study microbes and the infections they can cause.

pandemic An epidemic that affects a large proportion of the population across a country or the world.

pneumonia A lung disease in which infection by a virus or bacterium causes inflammation and tissue damage. Sometimes the lungs fill with fluid or mucus. Symptoms include fever, chills, cough and trouble breathing.

SARS, or severe acute respiratory syndrome An infectious disease that emerged in 2002 and quickly spread to infect more than 8,000 people, killing nearly 800 of them.

virologist A researcher who studies viruses and the diseases they cause.

virus A molecule containing genetic information and enclosed in a protein shell. A virus — which can cause illness — can live only in the cells of living creatures. Although scientists frequently refer to viruses as live or dead, in fact no virus is truly alive. It doesn’t eat like animals do, or make its own food the way plants do. It must hijack the cellular machinery of a living cell in order to reproduce.