Cool Jobs: Delving into dung

Scientists uncover fascinating secrets through the study of animal feces

Sam Wasser’s team has trained dogs to search for the poop of rare animals. Here, a dog named Mason finds maned wolf dung in Brazil.

Matt Baker

By Roberta Kwok

Beginning in the late 1970s, Sam Wasser spent years following wild yellow baboons across Tanzania, a country in Africa. Wasser wanted to measure chemicals called hormones in the female monkeys to better understand their reproductive patterns. But the biologist didn’t want to stress the baboons by capturing the animals and sampling their blood.

Then an idea struck Wasser: What if he measured the hormones in baboon droppings? “One thing I knew about following baboons is they’re pooping a lot,” recalls Wasser, who now directs the Center for Conservation Biology at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Since then, Wasser has studied the dung of these animals. And not just baboons, but also grizzly bears, jaguars, armadillos, whales, elephants and other animals. Poop has taught him a lot about these creatures. For example, a pile of dung doesn’t just reveal the species that excreted it. Poop also contains important information about the animal’s travels, diet and health. These samples are especially helpful when studying rare or endangered species.

Feces fascinate scientists tackling other topics too. Some scientists search for ancient poop left by animals that have gone extinct. Quite a few even study critters that dine on dung. Sure, feces may not be pleasant. Still, the researchers profiled here believe the knowledge they derive outweighs any drawbacks.

Just ask Emily Baird, a biologist at Lund University in Sweden, who studies dung beetles: “We’re usually encrusted in dirt and poo by the end of it, but we love it.”

Hunting for poop

After studying baboon feces, Wasser realized the same technique could help him learn more about other animals without studying them directly. When an animal poops, the droppings contain cells from the creature’s own digestive tract. Those cells contain DNA, a molecule unique to each animal. Just like a fingerprint, DNA could tell Wasser which species — and even which individual animal — it came from. He would first collect and analyze the feces, or scat, of a particular species across a given area. Wasser then could study the size and health of that animal’s local population.

But there was one problem: When animals are rare, so is their poop. Wasser needed help.

So he turned to dogs and their amazing sense of smell. Already, dogs help us by sniffing out bombs and drugs. Why not scat? The best dogs for these tasks are obsessed with playing ball. Wasser’s team trained dogs by rewarding them with a ball for finding scat. Soon, the pooches were searching for poop with incredible focus.

In one study, the dogs found the scat of cougars, jaguars, maned wolves, giant anteaters and giant armadillos in a dry part of Brazil called the Cerrado. These five animal species are losing their natural habitat as people carve it up for farming. So the researchers mapped where the species pooped. That revealed the animals used pockets of unspoiled land as “stepping stones” to cross the landscape. The team’s findings showed that to help conserve those animals it was important that farmers preserve these patches.

The dogs worked really well on land. Wasser wondered if they also could sniff out scat offshore. He was particularly interested in a population of orcas — killer whales — in the Pacific Northwest. Those marine mammals had been declining in number but scientists haven’t known why. One possibility was that boats stress the killer whales. Another was the orcas haven’t been getting enough fish to eat. If Wasser’s team could find and study enough orca poop, it could provide some answers.

Wasser shared his idea for using dogs to hunt whale scat. Other scientists scoffed. “‘You’re crazy. You’ll never be able to find it,’” he recalls their saying. “I said, ‘Oh yeah?’”

So Wasser’s team trained a black Labrador retriever mix named Tucker to sniff out whale feces. The dog leans over a boat’s bow, its nose in the wind, and points researchers to any whale scat it smells. For one study, the team collected 154 samples of orca poop, found by following Tucker’s lead or sometimes just trailing the whales.

In the laboratory, the researchers measured levels of a hormone called GC, or glucocorticoid (GLU ko KOR ti koid) in the orca poop. Animals make more of this chemical when stressed or starved.

Every August, there were plenty of fish for the whales to eat — and a lot of whale-watching boats in the area too. Around that time, GC levels in the whale poop dropped to their lowest levels, the team found. If the boats stressed the whales, then GC levels should have been high at that time.

Later, when the number of Chinook salmon, a favorite food, dropped, GC levels in the orca scat rose. So the researchers concluded that fewer fish created more stress for the whales than did more boats. That is worrisome, because Chinook salmon are scarcer as people overfish this species.

Dung eaters

Back on land, Baird works with scat because it’s a dung beetle delicacy. These insects feast on the feces of everything from donkeys to monkeys. Some dung beetles shape manure into little balls. An individual beetle rolls that ball — “like a lunchbox or takeaway” — to where it can eat in peace, explains Baird.

And that roll always travels a straight line. This rolling behavior fascinates Baird. For example, she and her team noticed that beetles often climb atop their balls. They then turn around, as if pirouetting. The researchers wondered why the beetles “danced” this way. Were the insects looking for obstacles? Checking their course? “We were baffled as to what exactly they were doing and why,” Baird says.

To find out, she and her colleagues set up an experiment at a farm in South Africa. They collected dung where cows congregated, an area the team nicknamed “Poo City.” Next, they released dung beetles near the manure. Soon, the insects began forming their tiny dung balls. Then the researchers put obstacles in each beetle’s path.

Baird’s team has investigated why some dung beetles climb onto their dung balls and turn around in a little “dance.” Credit: Emily Baird

In one experiment, the researchers made a beetle roll its ball into a plastic tunnel and collide with a door that closed off the far end. In another, each beetle was forced to roll its ball through a curved tunnel — one that ultimately took it off-course.

Beetles confronted with these disruptions danced on their dung balls much more often than did the beetles left undisturbed. These findings suggested the insects danced to orient themselves and get back on track. For example, a beetle might check the position of the sun to aid its returning to the right path. And by looking around from atop its ball, the beetle also might prevent losing its lunch to another hungry beetle.

But the researchers still weren’t satisfied. The beetles seemed to climb atop their balls more frequently at midday, when it was hot. When Baird’s team cooled down the surrounding sand, the beetles clambered up less frequently.

Because dung is moist, it’s usually cooler than the sand. Baird and her colleagues wondered whether the beetles climbed up to cool their feet.

To test this, the researchers painted liquid silicone onto the beetles’ feet. The silicone hardened into tiny boots that would shield the beetles’ feet from the hot sand. Sure enough, booted beetles didn’t climb their dung balls as often as before. This suggested the beetles indeed had been trying to avoid hot feet.

Dung beetles so charm Baird, she can easily overlook the fact that they eat dung. “They are extremely cute,” she says. Once you fall in love with the beetles, she adds, you don’t mind that they live to dine on animal poop.

Dropping history

Scientists like Jamie Wood are used to being teased about studying poop. “I’ve pretty much heard every single joke there is,” says Wood, who works at Landcare Research in Lincoln, New Zealand.

Poop wasn’t part of Wood’s original plan. As a child, he joined a nature club and became intrigued by the many unique animal and plant species in New Zealand. In college, he decided to be a paleontologist, someone who studies ancient plants and animals.

During graduate school, Wood traveled to a region in southern New Zealand called Otago. About 700 years ago, huge fires wiped out a lot of the area’s wildlife. Wood wanted to learn more about the plants and animals that used to live there. He began seeking out preserved, or fossilized, remains of those species.

In one cave, Wood scraped away some dirt to make an amazing discovery: some large feathers. He had discovered an old nest made by moa, which were large, ostrichlike birds. Humans hunted to extinction the last of the wingless moa about 500 years ago.

Along with the feathers, Wood uncovered fossilized moa poop. Called coprolites (KO pro lytes), fossil feces are almost as hard as rock. Wood ended up gathering more than 1,000 moa coprolites from about a dozen caves and rock shelters throughout Otago.

Back in the lab, Wood’s team broke open the coprolites to investigate what the moa had eaten. They found seeds and leaf fragments from herbs and short plants. That was surprising because moa grew as tall as 6 feet (almost 2 meters). One might expect the birds to have nibbled mainly on trees.

Wood also grew interested in a living bird, the kakapo. These big, bright-green parrots come out at night. And like many birds in New Zealand, they can’t fly. Today, only an estimated 125 kakapos live in the wild.

As with the moa, Wood thought poop could tell him more about the endangered kakapo and its natural diet. Unfortunately, kakapo droppings are as rare as the birds themselves.

Instead, Wood and his team began studying coprolites from kakapo that had lived 850 to 1,000 years ago. At that time, the birds lived across a much broader area of New Zealand. That probably allowed ancient kakapo to interact with more species than do their descendents today.

In fact, the team soon discovered the ancient poop contained the pollen of a strange plant called Dactylanthus taylorii. The plant, also known as the Hades flower, grows underground and pokes its flower up through the soil. Today, the Hades flower is also in decline. In the past, when larger numbers of both species overlapped, kakapos probably dined on the flowers, Wood says.

While the flower fed the bird, the bird probably also helped the flower. Kakapos have whiskerlike feathers just right for picking up pollen when they feed on a Hades blossom. When the parrots transferred that pollen from flower to flower, it would have pollinated the plant. Wood suspects kakapos could help the Hades flower thrive again. Scientists recently moved some kakapos to an island where Hades flowers grow, so Wood may soon find out if his hunch is right.

The research done by Wood and the other scientists profiled here emphasizes why studying poop can help us better understand (and help) species too rare or too difficult to study directly. Says Wood: “It might seem quite a weird thing to do, but it does actually have applications in the real world.”

Power Words

hormone A chemical made by the body in tiny quantities that affects different processes, including growth, mood and reproduction.

DNA The genetic instructions inside cells that contain all the information needed to build or maintain an organism.

moa Large, wingless birds that lived in New Zealand until going extinct about 500 years ago.

coprolite Fossilized dung.

kakapo A large, nocturnal and flightless parrot that lives in New Zealand.

pollen Powdery grains released by the male parts of flowers. Pollen fertilizes the female tissue in flowers of the same species.

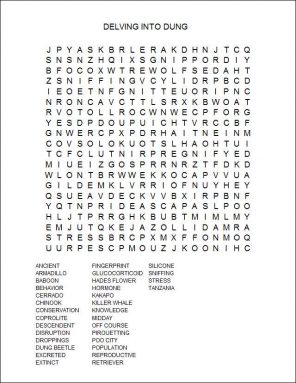

Word Find (click here to print puzzle)

This is one in a series on careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics made possible by support from the Northrop Grumman Foundation.