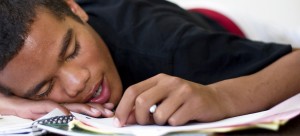

Making light of sleep

Teens are prone to sleep problems, but a little sunshine could help

monkeybusinessimages/istockphoto

By Susan Gaidos

Maybe this has happened to you: In the middle of class, while you pretended to be paying attention to the teacher’s lecture, your eyelids started to droop. You began having second thoughts about staying up late on Facebook the night before.

Don’t be too hard on yourself. Your computer screen may be to blame. And your clock may be too. Not the clock on your nightstand, but the one in your head. All mammals have a clock located inside their brains. Similar to your bedside alarm clock, your internal clock runs on a 24-hour cycle. This cycle, called a circadian rhythm, helps regulate when you wake, when you eat and when you sleep.

Somewhere around puberty, something happens in the timing of the biological clock. The clock pushes forward, so adolescents and teens are unable to fall asleep as early as they used to. When your mother tells you it’s time for bed, your body may be pushing you to stay up for several hours more. And the light coming from your computer screen or TV could be pushing you to stay up even later.

This shift is natural for teens. But staying up very late and sleeping late can get your body’s clock out of sync with the cycle of light and dark. It can also make it hard to get out of bed in the morning and may bring other problems, too. Teenagers are put in a kind of a gray cloud when they don’t get enough sleep, says Mary Carskadon, a sleep researcher at Brown University in Providence, R.I. It affects their mood and their ability to think and learn.

But just like your alarm clock, your internal clock can be reset. In fact, it automatically resets itself every day. How? By using the light it gets through your eyes.

|

|

Researcher Mariana Figueiro helps middle school student Carolyn Cimo test a pair of orange goggles and a Daysimeter™ headset that were used in the first field study showing the connection between sleep problems and lack of exposure to morning light.

|

| From the lab of Mariana Figueiro/RPI |

Scientists have known for a long time that the light of day and the dark of night play important roles in setting our internal clocks. For years, researchers thought that the signals that synchronize the body’s clock were handled through the same pathways that we use to see.

But recent discoveries show that the human eye has two separate light-sensing systems. One system allows us to see. The second system tells our body whether it’s day or night.

Blue light special

Light is detected by the eye’s retina. The retina contains millions of light-sensitive cells called photoreceptors. Two important types of photoreceptors are rods and cones. When they detect light, rods and cones pass the visual signal from nerve cell to nerve cell to the visual processing part of the brain. There, the signals are analyzed to tell you what you’re looking at.

A few years ago, scientists discovered another type of light-sensitive cell in the eye. These cells are called melanopsin ganglion cells. Like rods and cones, these ganglion cells are found in the retina. But unlike rods and cones, melanopsin ganglion cells send their signals to the part of the brain that regulates the body’s master clock.

The light signals sent to your body’s master clock tell you when to be sleepy and when to be alert. But not just any light will do. The circadian clock can distinguish between different colors, or wavelengths, of light. Blue light — such as the light from the blue sky — is best for stimulating the circadian system. In experiments, people exposed to blue light become less sleepy and more alert.

Sunlight is an excellent source of blue light. Although the light from the sun looks white, it is actually a combination of many colors, including blue light. This might explain why stepping outside on a bright sunny day helps clear the fog from your head.

Exposure to the morning sun is best for synchronizing the body’s clock with the Earth’s natural 24-hour cycle of light and dark. If you wake early and get outside, the body’s master clock tends to shift earlier, says Mariana Figueiro, a scientist at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y. That means you’re alert when it is light outside and sleepy when it’s dark.

The problem is, adolescents and teens may have limited exposure to the morning light. Often, they are on a bus or in class during the peak morning hours. Recently, Figueiro ran an experiment to see how exposure to morning light affects the circadian clocks of middle school students. She traveled to Smith Middle School in Chapel Hill, N.C. This school’s building is designed to provide daylight throughout the entire building.

Half of the students in the group wore orange-tinted goggles during morning school hours for one week. The glasses allowed enough light for the students to see, but blocked blue light coming in through skylights. Students in the other group had full access to daylight.

Each day, the scientists measured how much light exposure each student received, using a special light meter placed on the headphones of the goggles. The researchers also gave students a series of tests to measure their reaction times and memory skills. And at the end of each day, the scientists collected some spit from each student.

The saliva was used to measure amounts of a hormone called melatonin. Hormones are the body’s messenger molecules. Melatonin is known as the “sleep hormone.” When it gets dim outside, your brain secretes melatonin, preparing the body for sleep. As kids mature, melatonin is secreted later and later in the evening. This makes it easier for teens to stay awake longer and later.

Figueiro predicted that getting bright light early in the day would help get the melatonin flowing earlier in the evening. If so, the students who wore goggles would get sleepy later. And that’s what she found happened in the experiment.

After five days, the students who wore goggles began producing melatonin 30 minutes later than students in the no-goggles group. Thirty minutes may not sound like much, but the difference could be seen: Kids who wore goggles got sleepy later in the evening and stayed up later. They were also less alert during the day and scored lower on the performance tests.

“That shows that it’s important to get enough light in the morning to make sure you are synchronized with solar day,” Figueiro says. “Especially if you find it hard to get out of bed in the morning or get to sleep at night.”

Finding your rhythm

To get morning light during the school year, researchers suggest, use your morning break — say, sometime around 9 a.m. or 10 a.m. — to go outdoors or look out a window. Also, try to spend a few minutes outside before going to school.

And wearing orange goggles to block out blue light may also be helpful. The trick is to wear them in the evening, not in the morning. Worn in the evening, blue-blocker goggles could protect you from getting too much daylight when your body should be winding down.

Carskadon, the sleep researcher at Brown University, says that’s because adolescents and teens may be less sensitive to light in the morning and more sensitive to light in the evening. Working at the computer or watching TV late at night can make matters worse. Computer screens, TVs and other electronic devices emit some blue light. The extra light input can push your master clock’s sense of night ever later.

In her studies, Carskadon is trying to figure out what’s going on in the brain to produce this delay. She runs a summer sleep camp to study sleep patterns in adolescents and teens. Hers is no ordinary camp with horseback riding and canoeing. It’s a research lab housed underground. In this windowless environment, all outside time cues are eliminated. No sunlight, no clocks, no TV or texting. Teens play, read, eat and, of course, sleep. Monitors record their brain waves, muscle activity and heart rates.

Staying up late may come naturally for teens, but that doesn’t mean it’s a good idea. If teenagers awaken for school before the final phase of sleep is complete, grogginess in class is inevitable. Grades can suffer. Sometimes, it becomes impossible to get to school at all.

Dr. Roger Green, a pediatrician in Kingston, N.Y., helps kids who have reached this point. He specializes in treating sleep disorders. He also has firsthand knowledge of the problems an incorrectly set clock can create.

He remembers being late many days during sixth grade and regularly missing the school bus in middle school. In high school, he was suspended for being late too many times. “I had sleep problems for years, but there was no one to help me,” he says.

Sleep problems can cause health problems, too. When 11-year-old Madyson Macejka’s sleep-wake cycle got out of sync with her daily schedule, she began to suffer from headaches. That’s when her mother took her to see Dr. Green.

Macejka was always a night owl, according to her mother. She liked to stay up late, and often found it hard to go to sleep at an early hour during the school week. During the week, Macejka had problems waking up for school. On weekends, she would often sleep until noon.

Green says this kind of pattern can knock the circadian rhythm totally off-kilter. By sleeping late on weekends, Macejka was disrupting her the sleep-wake cycle for the whole week. “It’s like having jet lag,” Green says. Jet lag happens when your circadian rhythm is running on a different day-night cycle than the day-night cycle of the outside world.

Kids who are struggling to get out of bed in the morning may need help resetting their internal clocks, he says. “You can’t just turn back the clock and make a big change overnight. The brain and the body and the timing systems don’t work that way.”

But gradual changes can be made. Green recommends starting out by going to bed at your regular time, but getting up a few minutes earlier each day. “You may start out with a late bedtime, but if you get up earlier every day, you will eventually go to bed earlier, too.”

Staying away from light in the evening is also important. That means no computer or TV in the bedroom. He also recommends getting out into the early morning daylight for 10 to 15 minutes.

It worked for Macejka. In just a few weeks she was able to get her sleep-wake cycle in sync with her schedule and with the sun’s cycle. She says she now feels more awake in class and no longer needs naps. Her grades have shot up, too. Now that’s nothing to make light of.

This story and other Science News for Kids features describing research in medicine and biology are supported with funding from The Lasker Foundation. The foundation and its programs are dedicated to the support of biomedical research toward conquering disease, improving human health and extending life.

Going Deeper:

Website for Mary Carskadon’s summer sleep program http://www.sleepforscience.com

Science News special issue on sleep. http://www.sciencenews.org/view/issue/id/48207/title/October_24th%2C_2009%3B_Vol.176_%239

TEACHER’S QUESTIONS

Here are questions related to the article.