Pathways to research: Connecting with scientists

Budding researchers get ahead by spending their free time working side by side with real scientists

That’s no hairnet: Emily Prentiss and brain scientist John Butler practice attaching special probes to the head of a fellow researcher at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. These probes record the brain’s electric pulses and helped Prentiss study how the organ reacts to sudden changes in the environment. The young student was able to complete the project with Butler’s guidance.

Courtesy of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Not many scientists begin their careers with a busted knee. But that’s exactly how Evan Olin, now 18, got his start. While a freshman at Ossining High School in New York, this competitive runner ran so fast and so hard that he sustained serious injuries to both legs. It kept him off the track for months. Rather than becoming discouraged by his limping gait, however, Olin turned to science. He started exploring how intense activities — like his long jogs — could harm the human body.

The summer before his sophomore year, Olin landed a spot working in the lab of Gregory Gutierrez at New York University. Gutierrez studies how human joints develop and function. Eventually Olin started plopping experienced joggers onto treadmills to see how they ran when forced to jog barefoot — a type of running that’s become popular among exercise fiends.

The teen discovered that newbies to barefoot running often still run like they’re wearing jogging shoes. In other words, they land heels-first rather than on the balls of their feet — and this can be dangerous. For his studies on runners’ strides, Olin was named a semifinalist in the 2012 Intel Science Talent Search. This annual research competition for high school seniors is sponsored by Society for Science & the Public, the parent organization of Science News for Kids.

Olin wasn’t the only scientist in the competition to develop skills while working in a real-world laboratory. A stint with a professional scientist’s team can offer budding researchers huge benefits, including access to costly or hard-to-find equipment. Even more importantly, a spot in a research lab can provide young scientists access to lots of helpful advice.

Olin says that his time with Gutierrez gave him a head start on becoming a researcher, a career path he may pursue further when he attends MIT in the fall.

Wendy Hawkins, executive director of the Intel Foundation, which sponsors the Intel STS competition, says that working in a lab gives young students the “crucial opportunity to argue and discuss ideas and research findings…the heart of how real science is done.” Plus, she adds, research shows that students who volunteer in a lab in high school are much more likely to study science in college — or even become famous scientists themselves.

Like a real job, but…

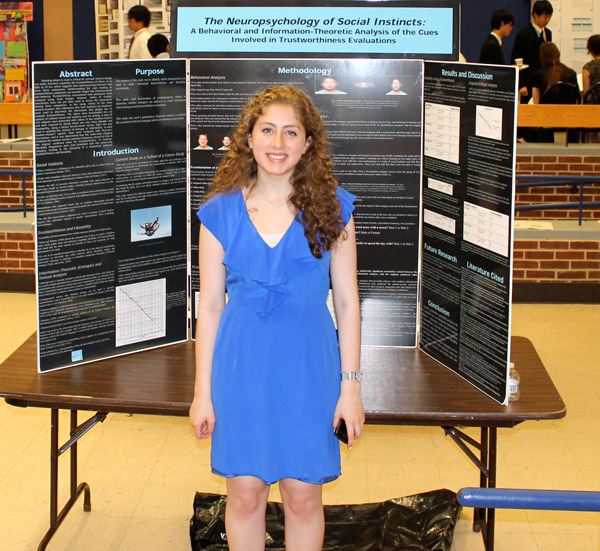

Such positions come with a catch: Lots of hard work. In fact, Emily Prentiss, another 2012 Intel STS semifinalist from Ossining High School, says that volunteering in a lab is a lot like having a real job — even if you don’t get paid. For instance, your colleagues definitely expect you to show up on time.

Prentiss, 18, got her start volunteering in the lab of John Butler, a scientist who studies the human brain at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City. While there, she explored how the brain reacts to a sudden change in the environment, such as a new sound or a touch from someone. She mapped how brain activity shifts when these changes occur using a technique that measures electric pulses in the brain. Such maps could help doctors who study the brains of kids with autism since loud noises can severely disturb children with this condition.

But to accomplish all of that, Prentiss really put in the hours. For two summers, she spent more than 20 hours a week in the lab, strapping sensors to peoples’ foreheads and monitoring their brain activity. Some young scientists put in even longer hours — up to 40 hours per week once the school year is over.

But it’s time well spent, Prentiss says. She now knows a lot more about what the life of a scientist is like. And she’s become more gutsy. Toward the beginning of her research, she felt shy around older students talking about topics she didn’t understand. “I was so intimidated,” she says. But by her second summer, “I could just walk into my mentor’s office and say, ‘I have a question.’”

Hunting down your mentor

For many students, however, the hard work begins long before they ever set foot in a buzzing laboratory. That was certainly the case for Olin as he began his search for a scientist who studies how the human body moves.

Olin was looking for a mentor — an expert who would take the teen under his or her wing, so to speak — guiding his training and research. To find the right individual, Olin read lots of scientific papers. These articles, often published online, report new data and analyze what those findings appear to mean. It was in one such paper that the high school student ran across Gutierrez’s name.

Claire Leibowicz, 17, who recently graduated from John L. Miller Great Neck North High School in New York, found her mentor in much the same way. She had been fascinated by the way humans behave. So in 2010 she emailed several researchers who study the human brain at Stony Brook University, close to Leibowicz’s hometown. In those messages, Leibowicz described the science classes she had taken and what type of research most interested her. She also asked a few thoughtful questions about the scientists’ own investigations. Leibowicz eventually connected with researcher Lilly Mujica-Parodi.

With the help of the Stony Brook scientist, Leibowicz wound up studying human trust. To do that, she turned to a group of people who know a thing or two about trust: skydiving instructors. These daredevils, after all, strap themselves onto the backs of people leaping out of planes. The only thing standing between customers and a quick splat are instructors — so they need to appear trustworthy.

You might expect that people would judge skydiving instructors based on their experience or looks. In fact, Leibowicz discovered, peoples’ opinions of these instructors — whether they came off as honest, reliable and responsible — seemed to be based mostly on the way they talked. For her surprising find, Leibowicz nabbed a 2012 Intel STS semifinalist spot.

Plenty of homework ahead

Real-life laboratory research doesn’t always go smoothly, these young scientists note. Olin, for instance, recalls he spent a while learning how to find and label all the muscles in a leg. Lab work takes “a lot of trial and error,” he says.

Other times, machines don’t work or the math doesn’t add up. “You will get stuck a lot of the time, and it will be so frustrating,” Leibowicz says. However, she adds, “when you overcome those hurdles, it will be so rewarding” because you know that it’s your project and nobody else’s.

Matthew McIntyre, 19, will be a sophomore at Boston University in the fall. While in high school, he worked with scientists at the New York Medical College in Valhalla to explore new ways to treat the deadly disease malaria. His research on the subject earned him awards at both the 2010 and 2011 Intel International Science and Engineering Fair, a program of Society for Science & the Public.

McIntyre has advice for students hoping to work on something interesting and important: Follow what’s hot. And that means paying attention to the progress of scientific research.

Where to start? Track the kinds of research frequently mentioned in newspaper or magazine articles, he says. Scientists working in popular, well-publicized fields often have more time and money to dedicate to young students, he explains. And look into well-funded research organizations, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in Seattle. Some post information right on their websites about what sort of research they’re funding.

But perhaps most importantly, McIntyre says, be well prepared before contacting a researcher. That includes reading a savvy scientist’s past and present research papers and the information on his or her personal website. But be forewarned: These papers can be tough to understand. So it wouldn’t hurt to ask teachers or guidance counselors where you might find experts who could help you understand the more challenging parts.

The payoff from all this hard work: “If you come in and really know what you’re talking about,” McIntyre says, “it really puts you ahead.” When scientists know you’ve already invested a lot of time in learning about what they do, it becomes easier for them to consider investing a lot of time in you.

Paul Roepe, a chemistry professor at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., can testify to that. He has mentored one high school student nearly every year for the past decade. He’s especially impressed when applicants come up with an idea for a project — even before they’ve met him. His latest high school protégé, for instance, told him right away that she’d like to investigate substances used to dry-clean clothes. Specifically, she wanted to find out how much of them remains on clothes after a cleaning.

But what he looks for most are students who are nerdy for science. “I’m not looking for someone who just wants a college recommendation,” Roepe says. “I look for someone who has the fire in their belly” — someone who exhibits real passion for investigating some aspect of science.

Miriam Rafailovich, a materials scientist at Stony Brook who designs new types of materials that can be used in electronics, says that young students can also add a lot of excitement to a lab. In fact, she likes having high school students in her lab so much that she helped launch a program to get young people into research. Each year, she and her colleagues pick 60 to 70 talented high school and college students and a few teachers and help match them up on research projects.

The experience has helped both the young students and the professional research scientists, Rafailovich adds. Once, for instance, she invited a woman named Brooke Ellison to speak to her students at Stony Brook. Ellison can’t move her arms or legs. But she can get around with the help of a wheelchair that she operates using a controller that she flicks with her tongue. Ellison told the researchers that she might be stranded if the battery in that controller died unexpectedly. So a team of young students in the audience took it upon themselves to design Ellison a new controller that could recharge its battery wirelessly, much like some cell phones.

If there’s “a crazy idea, they’re always willing to try it,” Rafailovich says. “Older people are much more cautious.”

Still, professional scientists and students alike agree that it’s important for mentors and their protégés to be good fits. Claire Leibowicz, for example, says that a high school student who is considering taking on a research project should find one he or she is really enthusiastic about. That way, if it blows up in their face — not literally, hopefully — they’ll still have had fun.

“If you choose a subject…you’re inherently interested in, your summer is going to be so valuable,” the teen says. Even if the first project you try doesn’t succeed, she explains, in the process you may discover what you really want to do with your life.

And that can be as thrilling as jumping out of an airplane.