Teens seek invention protection

Increasingly, young researchers seek patents to defend their innovations against theft

By Kellyn Betts

Naomi Chetan Shah didn’t think much about the air inside her Portland, Ore., home until she was 11. Then the sixth grader began to wonder why her father and brother always had watery eyes and runny noses. They suffered all year. That seemed to rule out seasonal allergies often caused by the pollen from blooming flowers, trees, grasses and weeds.

It took Naomi until high school to sleuth out what caused her family’s health problems. She even invented a computer program to help others diagnose similar problems. Her project earned her a spot as a finalist in this year’s Intel Science Talent Search (STS). This premier research competition is for students in their last year of high school. The Society for Science & the Public (which also publishes Science News for Kids) developed and runs the prestigious science competition.

While Naomi, now 17, hopes her computer program can help others, she doesn’t want anyone to steal her invention either. So she’s seeking to patent it. Governments offer patents for new inventions. These can include new processes, devices, substances or even plant varieties. Anyone who develops such a novelty can submit an application to the government.

In the United States, the Patent and Trademark Office reviews these applications. If this agency does grant Naomi a patent, it will give her the legal right to keep anyone else from making, using or selling her invention in the United States.

For a young inventor, a patent attests that his or her achievement is unprecedented, says John F. Ritter. He is a patent lawyer in New Jersey, and directs Princeton University’s Office of Technology Licensing.

While adult engineers, scientists and other inventors submit most patent applications, there is no age limit. Many young inventors seek patents to protect their inventions, also known as “intellectual property.” The Patent Office has issued at least one patent to a 5-year-old!

This year, 17 of the INTEL STS semifinalists and finalists, including Naomi, either have applied for a patent or have already received one. Additionally, another 20 semifinalists and finalists plan to seek a patent on their inventions.

Their experiences suggest that all students who invent something, even if they don’t participate in a science fair, should at least know about patents. And if they are interested in obtaining a patent, they should apply as early as possible!

Scents and sensibility

Naomi credits the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for launching her six-year investigation into indoor air. Indoor levels of pollutants may be two to five times higher than outdoor levels, according to the agency. That is significant, since most people spend more than 90 percent of their time indoors. Still, Naomi was surprised to learn that very little research had been conducted on the health risks of indoor air pollution.

So starting in middle school, she learned how to collect air samples. Then, she worked with chemists at nearby Portland State University to analyze those samples. She also learned to measure how well the lung inhales and exhales while we breathe.

By high school, Naomi had collected enough data to identify the source of the respiratory problems that afflicted her father and brother. As part of her family’s Indian heritage, they regularly burned incense and scented candles. That released tiny irritating particles into the air. When the family — at Naomi’s recommendation — burned fewer of these products, the girl’s brother and father suffered less.

The young researcher went on to recruit more people for testing. Naomi also sampled the air inside their homes, schools and workplaces. Her sleuthing revealed several types of air pollutants known to trigger allergy symptoms. These included a family of chemicals known as volatile organic compounds, or VOCs. VOCs include toluene, xylene and styrene, used in building materials, paints, furniture and cleaners. Naomi so far has amassed more than 4 million air samples. She has also collected lung health data from more than 100 volunteers.

While in tenth grade at Portland’s Sunset High School, Naomi wrote a computer program to process her data. One year later, she presented this computer program at science fairs and competitions, pointing out its potential use in predicting how indoor air can affect lung health.

Act fast

Naomi realized she should patent her invention if she was going to make her computer program publicly available. With her father’s help, she began to investigate how to do that. She soon learned it was too late. Presenting her invention at science competitions is a form of publishing, she learned. And U.S. patent law says that once inventors publish, or make public, their inventions, they have only 12 months to start the patent application process. Naomi had missed out.

But all was not lost. By modifying her computer program — making it different, and therefore new — she could seek a patent on the revised version.

INTEL STS finalist Catherine Wong was quicker to apply. Soon after Catherine began showing her first invention at science fairs, one of her teachers at Morristown High School in New Jersey recommended that she think about patenting it. For $125, she was able to protect two of her inventions for a year with what are called provisional patents. These are essentially temporary patents. She followed up by applying for a much more expensive standard patent on one of her inventions.

Catherine, now 17, credits an experience she had while in seventh grade for inspiring the project that landed her in the INTEL STS finals. While visiting a museum exhibit in New York City, called Design for the Other 90%, Catherine learned that most people in the world have little or no access to the products and services available to people in the United States and other industrialized nations. Nearly half of the world has no dependable access to food, clean water or housing.

Three years later, Wong enrolled in a high school research science class. While investigating potential projects, she learned that more and more of the world’s people were getting mobile phones. (Today, more than 6 billion people have them!) Catherine decided to create a new type of stethoscope based on the popular handheld communication device.

Such an invention could bring medical help to people living in remote areas with no doctors. The device would work like a regular stethoscope that a doctor places on your chest or back to listen to your heart and lungs. But the device would also work with a cell phone, amplifying the sound enough for a doctor on the other end of the line to hear it clearly, Catherine explains. That way, doctors could diagnose illnesses in faraway patients.

Catherine relied on a book entitled, Make: Electronics, for guidance on how to create the circuits in her “wireless stethoscope.” Once completed, the device was roughly the size of a bar of soap. And what will a doctor hear when it is used? The sound is “much like the drumbeat of your pulse against your ears after a run,” Catherine says.

More recently, Catherine built a second, related device to amplify and record the heart’s electrical activity. It creates a digital record of someone’s heart rate. Both inventions wirelessly transmit the data they pick up from the body to nearby mobile phones.

When time came to apply for a patent for her wireless stethoscope, Catherine quickly learned it could cost tens of thousands of dollars to get needed help from lawyers. Rather than be discouraged, she called roughly 10 patent lawyers before finding a firm that could help her for a more affordable price. Luckily for Catherine, her parents helped by paying the still steep $5,000 bill.

Catherine says that getting her earlier, provisional patent proved useful when the time came to file for a standard patent. “Writing up a provisional patent forces you to break down exactly what you’ve done — the methods, what the benefits are — and to really begin to examine if it is something that is patentable,” she explains.

Avoiding lawyer’s fees

Alison Dana Bick, 19, took a different path to patenting. She invented a way to test for bacterial contamination in drinking water, using common household materials. Rather than apply for a provisional patent, however, Bick went for the whole enchilada. And by filing her own application, she avoided paying expensive fees to lawyers.

It was just that sort of self-reliance that inspired Bick’s invention.

When she was in eighth grade, a major storm hit her hometown of Short Hills, N.J. Afterward, health officials warned the community’s water supply might not be safe to drink. But was it polluted? Bick invented a simple system to evaluate water contamination. It uses a cell phone’s camera, a light (even the light from a second cell phone) and a plastic bag.

First, you fill the bag with water and shine a bright light on it. Next, you take a photo of it. Finally, a computer program Bick developed analyzes the photo to determine the concentration of fecal coliform bacteria. These germs point to sewage, which can often taint water following major storms. The project won Bick, now in her second year at Princeton University, a spot as a finalist in the 2011 Intel Science Talent Search.

Bick spent the summer before her final year of high school preparing her patent application. “I want to do research for a living and I thought it would be a great experience to patent this device,” she explains. She relied mainly on information she found online and in a book called Patent It Yourself. She spent less than $200 to file her patent. With its help, and a lot of patience, she has successfully patented her invention.

Of course, inventors don’t have to file for a patent in the country in which they live, notes Haejun “Brian” Cho. The high school senior at Milton Academy, in Milton, Mass., spent the summer after tenth grade in South Korea. There, Brian performed research working with Eric Choi. He’s a materials scientist, mechanical engineer — and family friend. From a laboratory in his apartment, Choi works on a variety of projects, including developing new soaps, using enzymes. Enzymes can remove the pore-blocking oils your skin naturally produces. While working with Choi, Brian invented a process that uses enzymes to replace some of the chemicals used in conventional soaps.

A major challenge is “keeping the enzymes active until they are applied,” explains Brian. That’s because enzymes can easily break down in response to changes in pH or temperature. The teen’s solution was to use microscopic spheres perforated with even tinier holes. Brian first fills the microspheres with the enzyme. Then he coats the little capsules with silicone oil to protect against changes in the environment. After the spheres are blended into soap, the silicone washes away only once it comes into contact with water. That way, the soap releases the enzyme just as you start washing.

With Choi’s assistance, Brian filed for a South Korean patent. It cost approximately $50 and took just six months to receive. Meanwhile, Brian has won a semifinalist’s slot at the 2013 INTEL STS competition for entirely different research into the materials that remain after the supernova explosion of massive stars.

Firm help

Pavan N. Mehrotra, 18, a finalist in the 2013 INTEL STS competition, also expects to receive a patent. Unlike the other teens we have met so far, Mehrotra didn’t have to even apply. The company where he interned applied for him.

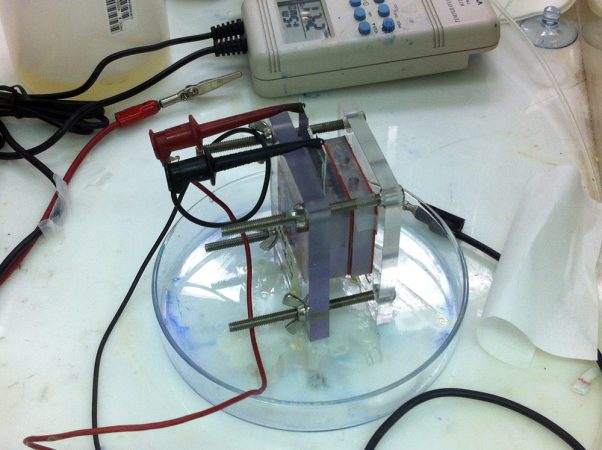

Mehrotra lives in Simi Valley, Calif., and attends the Sierra Canyon School in nearby Chatsworth. After his junior year of high school, Mehrotra landed a summer internship with nearby Teledyne Scientific & Imaging. Its researchers develop high technology products, including fuel cells. Fuel cells work by converting chemical energy into electrical energy. The technology has interested Mehrotra since he was in middle school.

As an intern — or student worker given the opportunity to learn and practice professional skills — Mehrotra was assigned to a project seeking to merge two types of fuel cells. One was a microbial fuel cell. It uses yeast and sugar to make electricity. But such fuel cells can’t make that much power by themselves, Mehrotra explains. They generate much more electricity when combined with a second fuel cell, one specifically designed to run on alcohol. Luckily, the yeast in the first fuel cell also makes alcohol.

However, merging the two types of fuel cells created problems. In the first fuel cell, the fermenting yeast didn’t just make alcohol, but other byproducts too. Those wastes fouled an expensive catalyst — or substance that speeds up chemical reactions — in the second fuel cell. That dramatically reduced how much electricity the combined fuel cells would make. Luckily, Mehrotra discovered a solution.

He found inspiration for it in the work he was doing on another Teledyne project. It used special membranes with super-tiny holes in them to remove the salt from seawater. Mehrotra reasoned that such membranes could do work in the combined fuel cell too. They would do double-duty, by allowing the alcohol to pass from the first fuel cell to the second, but blocking any of the bothersome byproducts. Through trial and error, the teen eventually discovered what size holes — or pores — would work best in the membrane.

Mehrotra’s mentor at the company, Rahul Ganguli, helped the teen determine that his solution was truly novel. The company applied to patent the invention, although Mehrotra didn’t know that until after returning to school. Teledyne envisions that the fuel cell will someday generate emergency power for soldiers. In time, it may even power consumer devices.

Ritter, the patent attorney at Princeton, notes that most corporations make their employees (including interns) give up their rights to anything they invent at work. So Mehrotra won’t get any money — called royalties — from companies using the patent. Still, the teen is grateful that Teledyne let him enter his invention in the INTEL STS competition.

Cred — and credit

Adults take teen researchers more seriously if they are seeking to patent their inventions, note the students interviewed for this story. Patents help adults look past the fact that “you’re just a high school student,” Catherine Wong explains. Indeed, her patent application helped establish her credibility with a University of Michigan researcher. She is currently working with him to improve her mobile cardiac device.

Patents also help discourage grown-ups from thinking a teen project addresses “a trivial problem or it’s easily stealable,” Catherine continues. And even a provisional patent can protect work from being copied by others researchers who might have heard a student talk about his or her invention, she adds. Adds Naomi Shah: Having a patent application suggests that there are good reasons to have confidence in your data and claims.

Finally, a patent is a surefire way of standing out from other students when applying to college. Bick says she is “sure it definitely helped” her get into Princeton University. Indeed, the 2013 INTEL STS finalists interviewed for this article already have won admission to top-tier schools, including Harvard and Stanford universities. As of this writing, none has formally accepted an offer.

Power Words

catalyst A substance that increases the speed of a chemical reaction.

enzymes Substances in plants and animals that increase the speed of biochemical reactions. For example, enzymes in your stomach help break down the food you eat.

fecal coliform bacteria Microbes present in the feces of all warm-blooded animals and humans. These germs are present in sewage, which can contaminate drinking water during storms.

fuel cell A device that converts chemical energy into electrical energy. The most common fuel is hydrogen, which emits only water vapor as a byproduct.

intellectual property An idea, method, process or written work that you have invented or created — and therefore that you initially own.

membrane A thin sheet of material that allows some substances to pass through it.

microbial fuel cell A device that relies on microbes to initiate a chemical reaction to generate electricity. These devices can use waste materials, including sewage and manure, to produce energy cleanly.

patent A legal document that gives inventors control over how their inventions — including devices, machines, materials, processes and substances — are made, used and sold for a set period of time. Currently, this is 20 years from the date you first file for the patent. The U.S. government only grants patents to inventions shown to be unique.

patent claim Claims are the part of the patent application where the inventor defines his or her invention for legal purposes.

patent pending Anyone who has filed for a provisional or standard patent can legally say they have a patent pending.

provisional patent A relatively quick, inexpensive and simple initial U.S. patent application that establishes when you initially filed for your patent. You must file for a standard patent before a year is up to fully protect your invention.

royalty A payment made in exchange for the use of a patented invention.

U.S. Patent Office The federal government agency in charge of U.S. patents.

volatile organic compounds Chemicals whose properties make them liable to escape into the air. They are often chemicals that you can smell in the air.

Word Find (click here to print puzzle)