Earthquake shortens the day

The recent South American quake sent Earth spinning just a big faster

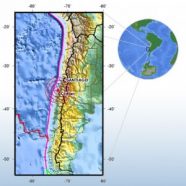

Just after 3:30 am on February 27, a powerful earthquake shook the central part of Chile, a country in South America. In cities including Santiago, the capital, some buildings collapsed and hundreds of people were hurt or killed.

Chile wasn’t the only part of Earth shaken by the quake, however.

According to studies done by geophysicists at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts, the earthquake affected the whole planet. The quake tilted the Earth’s axis — an invisible line around which our planet rotates — a few centimeters. And, even more surprisingly, that earthquake shortened the length of a day.

To understand how an earthquake can change the length of a day, it’s important to understand what causes an earthquake in the first place. The Earth’s outer shell, or crust, is like a jigsaw puzzle, made of giant pieces that fit together. These pieces are called tectonic plates. Scientists have identified seven large plates and many other, smaller plates.

Unlike the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, tectonic plates do not always fit together well. Each plate moves on its own, and plates are continuously moving. As a result, they may collide, move apart or slip past each other. The border between two plates can be a violent place, home to explosive volcanoes or — as in the case of Chile — earthquakes.

At the boundaries between them, the plates may get stuck for long periods of time and then slide past each other quickly. That’s what happened on February 27, when rocks on the boundary between the Nazca and South American plates slipped past each other by 20 or 30 feet, Lin says. The quake let go stress that had been building between the plates for tens if not hundreds of years. The first earthquake struck just after 3 a.m., but in the next week people in Chile experienced 180 “aftershocks,” which are other quakes — often less powerful — that follow after the first. These earthquakes may have shifted and sped up the rotation of the Earth, according to Lin and other scientists.

As buildings collapsed in South America, a large portion of the Nazca plate headed down toward the center of the Earth very suddenly. When the mass inside the Earth moves around, the planet may change the way it spins — in this case, the axis shifted by a bit. But our planet also picked up speed. Richard Gross told Science News that one way to think about it is to imagine an ice skater, spinning in a circle with her arms outstretched. As she brings in her arms, she starts to spin faster.

And because the quake was in the Southern Hemisphere, the change in mass happened in just one part of Earth, as if the skater had pulled in only one arm. So Earth’s rotation axis tilted a bit.

Similarly, but on a much bigger scale, more mass went toward Earth’s center, and it started spinning faster. And when the Earth spins faster, days get shorter. But don’t worry — you probably won’t miss the lost time. The earthquake shortened an Earth-day only by about 1.26 microseconds — not even enough time to blink.