The return of a king

Skeleton of King Richard III, unearthed from an English parking lot, tells a grisly tale

In February, scientists from the University of Leicester in England announced that a skeleton discovered beneath a parking lot indeed belonged to that infamous King of England.

Richard III ruled England for two years before dying on the battlefield on August 22, 1485. Historians of the time portrayed the monarch as a ruler with a twisted spine who suffered a gruesome death. (Playwright William Shakespeare also wrote about the ill-fated king. At the end of the play bearing the king’s name, Richard is slain shortly after famously crying out: “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!”)

Scientists who have been studying the recently unearthed bones say those historic reports probably weren’t far from the truth. To borrow from Welsh poet Dylan Thomas, the king did not go gentle into that good night.

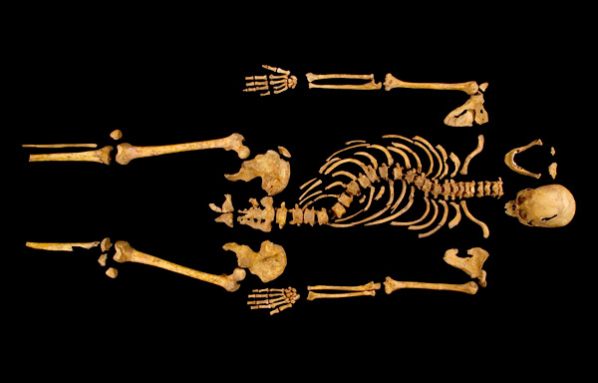

In August 2012, researchers from the university went in search of Richard’s remains. They excavated a parking lot next to a city council building in Leicester. Beneath the lot they found the walls of the Grey Friars church, where they believed Richard III was buried. Sure enough, in a small grave under the church ruins, the scientists found the skeleton of a man with a spine curved like a question mark and apparent battle wounds.

Those bones can give us some idea of what happened to Richard in his final hours. A close study of the skull shows a large hole in the back of his head: He was probably killed by the blow of a large blade. But the body also showed evidence of nine additional wounds.

Jo Appleby, an archaeologist at the University of Leicester, studied the bones. She says Richard’s ribs and pelvis had marks showing where a knife or dagger was used to pierce the king. If the king had been wearing protective armor, those attacks would have been deflected. These non-head wounds, intended to humiliate the king, Appleby says, probably happened after his armor had been removed. That would likely have been as he lay dying or just following his death.

After death, the king’s hands were tied and he was taken on the back of a horse to the church in Leicester, according to historical accounts. Paul Hyams is a historian at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. He studies conflicts in the Middle Ages, a period of European history from about 500 to 1500. He told Science News that back then, people would have been in a hurry to bury the body.

“The last thing the victors wanted was to give him a nice tomb in Westminster Abbey and have people put pretty flowers on it,” Hyams said. Seventeen monarchs are buried in the famous London church, which is more than 700 years old.

Scientists have been busy trying to learn more from the unearthed bones. Some researchers have used the skull to construct a model of the face, to see what the king looked like. Chemical analyses of the bones indicate that their owner dined on meat and seafood. Those foods were rare in the 1400s, fit mostly for a king.

Turi King of the University of Leicester has been studying genetic material taken from cells in the bones. Her team says this genetic material is very similar to that from present-day descendants of Richard’s family. To further confirm the bones belong to the king, the scientists are now conducting even deeper studies into another type of genetic material.

“I’m dying to get on with it,” King told Science News.

Power Words

archaeology The study of human history and prehistory through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains.

genetics The study of genes and their functions.

descendant A blood relative of a person who lived during a previous time.