A classroom of the mind

Computer technology that puts kids in a cartoon classroom may help them learn to pay attention.

By Emily Sohn

You’re sitting at your desk. A teacher is writing on the chalkboard. A bus rumbles past the window. Kids are yelling in the playground outside. A paper airplane whizzes overhead. The school principal steps into the room, looks around, and walks out. A book falls off the desk next to you. Suddenly, the teacher hands you a pop quiz.

Don’t panic! You aren’t actually in school. You’re in a “virtual classroom.” Everything you see and hear is coming to you through a computer-operated display that you’re wearing on your head like a pair of very bulky goggles.

|

|

Wearing special headgear allows this girl to see images and hear sounds that make her feel that she’s in a classroom.

|

| Skip Rizzo |

Unlike the classroom, the technology is real. It’s an innovative application of virtual reality, a type of technology that uses computer programs to simulate real-world (or even fantasy) situations. Wearing virtual-reality gear, you can find yourself sitting in a classroom, touring a famous museum, wandering across a weird landscape, zooming into space, or playing with a cartoon character. You don’t have to leave your room.

Movie directors and video game producers have been using computers for years to create ever more realistic special effects. Some companies are now building three-dimensional fantasy worlds in which players, linked by computer networks, appear to meet and go on quests together. Virtual-reality gear that delivers images and sounds directly to your eyes and ears makes these fake worlds seem lifelike.

Some psychologists are also getting into the act. They see virtual reality technology as a useful tool for learning more about why people act as they do. It could help psychologists better identify and come up with solutions for behavior problems, for example.

“We’ve spent the last 100 years looking for certain laws in how people interact with the real world,” says clinical psychologist Albert “Skip” Rizzo. “Now, we’ve got a powerful tool that lets us create worlds, control things, and see how people perform. This is a psychologist’s dream.”

Rizzo works in the school of engineering at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, where he developed the Virtual Classroom and a related program called the Virtual Office.

Virtual classroom

Some kids can’t sit still for long. They have a hard time paying attention to just one thing. They’re easily distracted. They can get very impatient. They hate standing in line or waiting for their turn in a game or activity. They get bored pretty fast. They may also be impulsive—saying the first thing that comes to mind or interrupting someone else who’s talking.

For certain kids, this problem is so severe that doctors have a name for it: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. Perhaps as many as 1 out of every 20 kids under the age of 18 have characteristics of ADHD. Often, these kids have trouble getting through school and face other difficulties later in life.

Rizzo started developing the Virtual Classroom in 1999. He wanted to see if he could use it as a tool for testing and treating kids who have attention disorders.

|

|

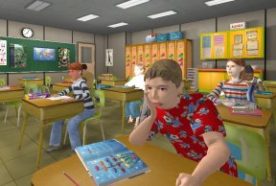

Here’s what you might see when you’re wearing virtual-reality headgear that puts you in a “cartoon” classroom.

|

| Skip Rizzo |

To diagnose ADHD, doctors typically test patients by giving them tasks that require attention. As part of one classic test, you watch letters flashed on a computer screen. Every time you see the letter “A” followed by the letter “X,” you have to press the space bar. If you’re paying close attention, you’ll register all the times this combination occurs. If not, you’ll miss some.

The Virtual Classroom makes these tests more efficient, Rizzo says. In one experiment, he gave a group of kids the classic “A-X” test. Instead of looking at a computer screen in a doctor’s office, though, the kids wore headsets that made it look like they were taking the test in a classroom.

“Basically what we found,” Rizzo says, “is that, in 20 minutes of testing with virtual reality, we replicated a finding that usually requires a couple hours of standard testing with computer screens in the psychologist’s office.”

Realistic features

Encouraged by these results, Rizzo and his colleagues started programming additional features into their Virtual Classroom. Introducing distractions was one of them.

Even though teachers try their best to keep their classrooms quiet and orderly, real life can get pretty chaotic. So, the researchers added people walking around, noises coming from the hallway, paper airplanes flying every which way, and other distractions.

|

|

A paper airplane glides through this virtual classroom scene.

|

| Skip Rizzo |

When Rizzo tested kids with and without ADHD using the more advanced program, he found some interesting patterns. Even without distractions, kids with ADHD performed worse on the “A-X” task than did kids without attention problems. When they had to deal with distractions at the same time, the differences between the two groups were even more striking, Rizzo says.

Because the Virtual Classroom more accurately mimics real life, diagnoses become more reliable than with traditional testing methods, Rizzo says. He thinks his program could reduce the number of kids who take Ritalin and other medications for ADHD because it does a better job of identifying the most serious problems.

The next step will be to move from diagnoses to treatments. Spending time in a carefully controlled Virtual Classroom might help train kids to pay better attention, even when facing the multitude of distractions that confront them every day.

That may be the only way psychology will ever keep pace with modern society, Rizzo says.

Information deluge

“We’re living in an information deluge,” he says. “One person estimated that a Sunday edition of the New York Times contains more information than a person was exposed to in their entire lifetime in the 18th century.” And there’s a lot more around than just the Sunday newspaper.

Kids are growing up in an increasingly high-tech, computer-dominated world. “We’re not going to entice this generation of kids in the classroom or later in job training with old, traditional tools,” Rizzo says. “Their brains are wired for speed. You can complain about that all you want, but this is reality.”

Grownups, too, stand a chance of benefiting from virtual reality technology. With a Virtual Office, adults with ADHD and others who have suffered from strokes or brain disorders might be able to retrain their memories or improve their ability to do two or more tasks at the same time.

While interviewing Rizzo, I found myself wondering if a Virtual Office might also someday be available to help writers get better organized.

Several groups of scientists around the world are looking for additional applications of virtual reality. One recent study found that the technology could help ease the suffering of children undergoing painful medical procedures. Kids who experienced a pleasant virtual reality while getting blood drawn or having healthy skin grafted onto severely burned areas appeared to feel less pain than those who simply watched a cartoon. In this case, distraction was a goal, not a problem.

As new applications arise and computer technology improves, it may get harder and harder to distinguish between the real and the virtual. Don’t get confused, though. Letting fly those paper airplanes might be okay in a virtual classroom, but it could get you into real trouble in a real one.