What Video Games Can Teach Us

If used in the right way, video and computer games can inspire learning and improve some skills.

By Emily Sohn

Part 2 of 2: Video Games—Good or Bad?

Last week: The Violent Side of Video Games

Here’s some news for you to share with your parents and teachers: Video games might actually be good for you.

Whenever a wave of teenage violence strikes, movies, TV, or video games often take the heat. Some adults assume that movies, TV, and video games are a bad influence on kids, and they blame these media for causing various problems. A variety of studies appear to support the link between media violence and bad behavior among kids (See The Violent Side of Video Games).

|

|

Video games can help focus attention. |

But media don’t necessarily cause violence, says James Gee. Gee is an education professor at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. “You get a group of teenage boys who shoot up a school—of course they’ve played video games,” Gee says. “Everyone does. It’s like blaming food because we have obese people.”

Video games are innocent of most of the charges against them, Gee says. The games might actually do a lot of good. Gee has written a book titled What Video Games Have to Teach Us About Learning and Literacy.

A growing number of researchers agree with Gee. If used in the right way, video and computer games have the potential to inspire learning. And they can help players improve coordination and visual skills.

Attention-getting games

A good video game is challenging, entertaining, and complicated, Gee says. It usually takes 50 to 60 hours of intense concentration to finish one. Even kids who can’t sit still in school can spend hours trying to solve a video or computer game.

“Kids diagnosed with ADHD because they can’t pay attention will play games for 9 straight hours on the computer,” Gee says. “The game focuses attention in a way that school doesn’t.”

The captivating power of video games might lie in their interactive nature. Players don’t just sit and watch. They get to participate in the action and solve problems. Some games even allow players to make changes in the game, allowing new possibilities.

And kids who play computer games often end up knowing more about computers than their parents do. “Kids today are natives in a culture in which their parents are immigrants,” Gee says.

In his 2 to 3 years of studying the social influences of video games, Gee has seen a number of young gamers become computer science majors in college. One kid even ended up as a teaching assistant during his freshman year because the school’s computer courses were too easy for him.

Screen reading

Video games can enhance reading skills, too. In the game Animal Crossing, for instance, players become characters who live in a town full of animals. Over the course of the game, you can buy a house, travel from town to town, go to museums, and do other ordinary things. All the while, you’re writing notes to other players and talking to the animals. Because kids are interested in the game, they often end up reading at a level well above their grade, even if they say they don’t like to read.

|

|

Now being developed, the educational computer game “Revolution” brings kids to colonial America. Players become characters in a small Virginia town in 1773. |

| Education Arcade |

Games can inspire new interests. After playing a game called Age of Mythology, Gee says, kids (like his 8-year-old son) often start checking out mythology books from the library or join Internet chat groups about mythological characters. History can come alive to a player participating in the game.

Even violent games have a positive side, Gee says. “Grand Theft Auto 3 does not exist to get off on shooting people,” he says. When the game begins, your character has just been released from jail. You need to figure out how to make a living, but the only people you know are criminals. Along the way, you might end up fighting or killing people, but you don’t have to.

“The game offers you a palette of choices,” Gee says. Players must confront moral dilemmas, develop social relationships, and solve challenging problems that might apply to real life, he says. “How compelling would a game be if you only had good choices?”

Improved skills

Video games might also help improve visual skills. That was what researchers from the University of Rochester in New York recently found.

In the study, frequent game players between the ages of 18 and 23 were better at monitoring what was happening around them than those who didn’t play as often or didn’t play at all. They could keep track of more objects at a time. And they were faster at picking out objects from a cluttered environment.

“Above and beyond the fact that action video games can be beneficial,” says Rochester neuroscientist Daphne Bavelier, “our findings are surprising because they show that the learning induced by video game playing occurs quite fast and generalizes outside the gaming experience.”

The research might lead to better ways to train soldiers or treat people with attention problems, the researchers say, though they caution against taking that point too far.

Says Bavelier, “We certainly don’t mean to convey the message that kids can play video games instead of doing their homework!”

|

|

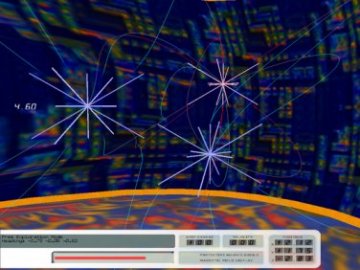

In the educational video game “Supercharged,” players can use magnetic fields to navigate mazes. Players also see electric field lines, which can help guide them through the course. |

| Education Arcade |

If Gee gets his way, though, teachers might some day start incorporating computer games into their assignments. Already, scientists and the military use computer games to help simulate certain situations for research or training, he says. Why shouldn’t schools do the same thing?

“Kids are beginning to see school as really out of step with culture,” Gee says. Making computer technology part of the learning experience could change all that.

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have started a project they describe as the “Education Arcade.” The project brings together researchers, scholars, game designers and others interested in developing and using computer games in the classroom.

Some kids already go to educational Web sites where they can interact with other kids and help solve problems. At Whyville (www.whyville.net/), for example, kids from all over the world can chat, build an online identity, and learn math and science as they roam a virtual world.

Looking at the bright side of video and computer games could also help bring kids and adults closer together. Playing games can be a social activity, during which kids and adults learn from each other. By opening up lines of communication and understanding, maybe one day we’ll praise video games for saving society, not blame them for destroying it.

On the one hand, there’s still a lot more to learn about how video games really affect us. On the other hand, there’s also a lot to learn about how to harness them for our benefit.

Part 1 of 2: The Violent Side of Video Games

Word Find: Video Games and Learning

Comments:

It is true that I learn easier when I can actually do something with what I learn—like figuring a math problem to unlock a door or to execute an attack!—Zachary, 13