Alien invasions

Around the world, plants, animals, fungi, and other life forms are ending up in places where they don't belong.

By Emily Sohn

The invasion is under way.

Around the world, plants, animals, fungi, and other life forms are moving into places where they don’t belong. These raids can mean major headaches for both wildlife and people.

Half of all endangered species can credit their shaky status to invaders that eat them, eat their food, or destroy their habitats, says ecologist Dan Simberloff of the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.

In New Orleans, alien termites are chewing up houses. In Florida, imported water hyacinth plants are choking rivers. Chestnut blight, caused by a fungus that entered the United States from Asia, continues to spread around the country, leaving stands of dead trees in its wake. The list of examples goes on and on.

|

|

The Formosan subterranean termite has invaded New Orleans. With its large, orange head and powerful mandibles, this one is a soldier. About 10 percent of a termite colony consists of soldiers who help protect the colony against intruders.

|

| Scott Bauer/U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service |

About 7,000 invasive species larger than microorganisms have come to the United States, Simberloff says. Roughly 10 percent of them cause problems. And the number of invasions is growing at an alarming rate. Already, the United States spends more than $130 billion dollars each year to battle the problem.

Still, these efforts aren’t nearly enough, Simberloff says. Governments must get organized, and people need to start working together now to have any hope of beating the crisis, he says. There are ways in which you can help.

Hitchhiking critters

About half of all invasive species get transplanted by accident, Simberloff says. Tiny insects can hide in the crevices of your muddy shoes when you fly home from a beach vacation. Mussels and other water organisms cling to ships as the vessels cruise from harbor to harbor.

Sometimes, it’s not an accident.

Consider the example of the boy from Hawaii who brought some snails to his grandmother in Miami. He thought she would love them. She thought they were gross and tossed them in the backyard. Scientists discovered the invasive snails a year and a half later, after the aliens had already pushed some native species close to extinction. It took 7 years and a great deal of money to get rid of the invaders.

Hitchhiking species aren’t new. Thousands of years ago when people started migrating to new areas, they brought desirable plants and animals with them. Other seeds and creatures came along accidentally. Many of our most important foods—such as wheat, potatoes, and corn—aren’t natives in the places where they now grow.

|

|

Although the flower of the water hyacinth is beautiful, the plant itself has become a floating nightmare in many tropical areas.

|

| Willey Durden/U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service |

Until fairly recently, travel was slow enough to keep most potential pests under control. Today, however, lots of people travel large distances every day. All this moving around, especially on airplanes, can lead to the rapid spread of undesirable species.

New Zealand does a great job in slowing the spread of alien species by thoroughly checking airport luggage for lurking creatures, Simberloff says. On the other hand, inspections in countries such as the United States lag far behind.

“You could bring in something by accident—or deliberately—without anyone doing anything,” Simberloff says.

The U.S. Congress is now considering passage of a new National Aquatic Invasive Species Act to help prevent the influx of alien critters into U.S. waters.

Simberloff doubts that the legislation will help much. Instead, it would be much more efficient to create a centralized department focused entirely on identifying and getting rid of invasive species, he says.

Simberloff also wishes for an invasive species hotline. “We ought to have a 911 number,” he says. “You could call and say, ‘I saw something weird. Does anyone know what it is?'”

Bad results

In the meantime, you can help keep the situation from getting worse by making sure you clean off your shoes and clothes before you come home from a trip. Shake out your duffel bags before leaving summer camp so that the bugs that belong in the woods stay in the woods.

And, scientists say, resist the temptation to transport plants and animals when you travel. Tourists sometimes stow lizards, parrots, bugs, and other exotic creatures in their luggage to bring home as pets or gifts. Their intentions are often innocent, but the results can be disastrous.

Even scientists sometimes make similar mistakes. Experts introduced Asian mongooses to Hawaii, for example, to control the island’s rat population. Hawaiian rats, though, are still thriving, and mongooses have driven more than 30 other species to extinction.

Sometimes, introduced species team up with each other to destroy ecosystems more effectively than either one could do on its own. Zebra mussels filter water, for instance, which allows a weed called Eurasian watermilfoil to grow in places it can’t normally grow. In return, the milfoil creates a hard surface on which zebra mussels can settle. The two invasive species help each other make a bad problem even worse.

Preventing disasters

In an effort to help prevent future ecosystem disasters, some scientists are studying the details of specific invasions. One of Simberloff’s projects involves ladybeetles. The two most common species of the insect in the United States today actually came over from Asia less than a decade ago.

|

|

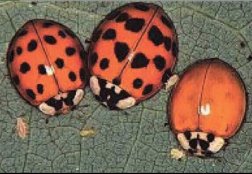

Introduced from Asia, the multicolored Asian ladybeetle is the largest and most abundant of all ladybeetles in Florida citrus groves.

|

| Florida Cooperative Extension Service/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences/University of Florida |

As part of an experiment conducted before the Asian bugs arrived, scientists collected data about ladybug populations in various places. Now, Simberloff and his colleagues are going back to the same places to collect the same kinds of data. They want to figure out why native ladybugs still survive in some places but not in others. The information may eventually help them find a way to keep the native ones around for good.

Scientists in the United States are doing the same type of research with Africanized honeybees, gypsy moths, yellow starthistle, and other invasive plants and animals. Learning basic facts about invasive species, they hope, will help them slow or stop the never-ending march of invasions.

There have been some success stories. Witchweed, for example, once covered 500,000 acres of North and South Carolina. With a great deal of effort, field workers have reduced the invasive plant’s territory to just 1,000 acres in three counties in North Carolina.

Similarly, the National Park Service managed to destroy an invasive population of gypsy moths in Utah between 1996 and 2001.

In the war between us and them, however, alien species appear to be on the winning side for now. As scientists struggle to develop countermeasures, there’s one bottom line that anyone can understand, Simberloff says. Don’t be the one who carries a critter to a place it doesn’t belong.

Going Deeper: