Alien carp leap onto the scene

Invasive fish break people’s bones and threaten native species

Silver carp jump out of the water when startled by a boat’s motor. These invasive species can break the arms, jaws and noses of boaters.

Asian Carp Regional Coordinating Committee

By Roberta Kwok

Last summer, Alison Coulter got a big surprise as she piloted a boat along the Wabash River in Indiana. Coulter is a scientist at Purdue University in West Lafayette who studies fish called Asian carp. She was trolling the river to track the movements of these non-native fish. Here, the river teemed with the invasive carp. Startled by her boat’s motor, a 60-centimeter (24-inch) carp leaped out of the river. The fish cleared the edge of the boat and whacked her right in the thigh.

Coulter got off easy. She sustained only a seven-centimeter bruise. In some cases, jumping Asian carp have broken a boater’s nose, jaw or arm. These fish have even knocked some people unconscious.

The carp pose other dangers too. People have been introducing these fish, originally from Asia, into many new countries, including the United States. Once the carp reaches a new river or lake, the species multiplies quickly. These invaders also gobble a lot of food. Scientists worry that might threaten biodiversity, or the number of species living in a region. Many of the species left to starve might be native fish. If that happens, people who earn their living by angling for native fish might have trouble.

To better understand the threat, scientists need to learn more about Asian carp. Some researchers are investigating how far these invaders have spread. Another team is studying where the carp can reproduce. And still others are probing ways to block the fish from colonizing new rivers and lakes.

People will need to act fast to stop the carp from continuing to spread. “Once they get into an area, it’s very difficult if not impossible to remove them,” says Cory Suski. “And then you’re stuck with them,” explains this biologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Big eaters

Asian carp refers to several species. Two of them, the so-called bighead and silver carp, probably pose the biggest threats in American waters. Silver carp typically weigh up to 9 kilograms (20 pounds) and bighead carp weigh twice that much (although some bigheads have tipped the scales at a whopping 45 kilograms). A female can lay up to 2 million eggs each year.

Bighead and silver carp are ravenous eaters. They swim with their mouths open, devouring algae, tiny aquatic animals called zooplankton and the eggs of other fish. “They’ll eat just about anything,” says Christopher Jerde. “If it’s small and floating in the water, they’ll eat it,” explains this biologist at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Ind.

In the 1970s, people thought such voracious eating habits might come in handy. Perhaps the bighead and silver carp would remove excess algae from ponds on fish farms. So people brought the carp from Asia and released them into fish farms in the southern United States.

But the fish escaped.

The Asian carp spread northward into the Mississippi River Basin. This huge network of rivers and streams drains about 40 percent of the lower 48 U.S. states. The fish began eating a lot of the small organisms in the water. Meanwhile, native fish that also eat those organisms started to lose weight. In short order, the numbers of Asian carp exploded. In some areas, these non-native species became the most common fish.

People started to worry that the carp might reach the Great Lakes. Containing more than one-fifth of the world’s surface fresh water, these five vast lakes straddle the border between the United States and Canada. Many native fish swim in those waters. If carp entered the Great Lakes, from there they could spread through connecting rivers and canals to even more of eastern North America.

DNA detectives

One possible pathway Asian carp could take into the Great Lakes is via a narrow canal passing through Chicago. It connects the Mississippi River Basin to Chicago’s shoreline along Lake Michigan, one of those Great Lakes.

In 2002, people installed an electric barrier to keep invasive fish from swimming through this canal. The barrier creates an electric field that makes fish feel uncomfortable. When fish get too close to this field, they should turn and swim in the opposite direction.

But the truth is that no one really knew whether the electric barrier was blocking Asian carp. “Most people did not know where these fish were,” explains Jerde.

One reason: Asian carp are hard to catch. So Jerde’s team looked for a better way to detect them.

The researchers decided to search the water for carp DNA. DNA is a type of molecule found in all living things. Animals from the same species have similar DNA. If Asian carp were present, they would shed scales and mucous containing their DNA. Their poop contains DNA as well. By testing the water, scientists might be able to find evidence of Asian carp, even without observing the fish directly.

In 2009 and 2010, Jerde’s team collected water samples along the Chicago canal and in other waterways in and near Chicago. They looked for evidence of Asian carp DNA. And, recalls Jerde, “We found their DNA in a lot of places nobody wanted to see it.”

It was upstream of the canal’s electric barrier. It turned up in waterways very close to Lake Michigan. The DNA even showed up in one part of the lake. The findings made Jerde feel “sick.” It was the last thing he had wanted to find.

And it got worse. In 2011, Jerde’s team identified Asian carp DNA in a second Great Lake: Erie. But tests of many other rivers and streams connected to Lake Michigan outside of the Chicago area came back negative. “The good news,” says Jerde: The DNA suggests these fish are not yet everywhere. Still, alien carp DNA in two of the Great Lakes is troubling. “It’s a red flag,” he says.

Egg hunt

Asian carp will spread and readily colonize a new region if they can reproduce in many types of rivers. These fish reproduce by spawning. A male releases sperm into the water. These reproductive cells can fertilize eggs deposited by a female fish. Over time, the fertilized eggs will float down a river and hatch.

Coulter wanted to find out whether Asian carp were particular about the water conditions needed to spawn. In Asia, these fish usually spawn in big rivers. Coulter wanted to probe whether that was true in the United States as well.

So she and her colleagues traveled down the Wabash River in Indiana by boat in 2011 and 2012. This river is part of the Mississippi River Basin. After netting eggs, the researchers brought them into the lab for identification.

To their surprise, the biologists found Asian carp eggs even in a narrow, shallow part of the river. That means the fish can reproduce in more places than scientists had previously thought possible. And the fish spawned over an extended period — from May through September. Being adaptable makes them an especially successful invader, Coulter concludes.

She is now studying how far and fast these carp swim. She’s also investigating whether their movements depend on temperature or the flow of the river. Knowing such details could help scientists predict where the carp will turn up next.

Researchers at the U.S. Geological Survey have studied whether Asian carp could successfully reproduce if they become more common in the Great Lakes. The fish will need to spawn in nearby rivers. A study published in June 2013 now indicates that four rivers connected to the Great Lakes have the right water conditions for Asian carp eggs to develop and hatch.

Keep out!

Scientists know that Asian carp are on the move. Can they be stopped?

An electric barrier isn’t foolproof. For example, fish might shield themselves from the electric field by swimming alongside barges, a type of boat. Suski, the scientist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, wanted to come up with a second line of defense.

His team wondered whether carbon dioxide, a gas, might block the carp. Fish can sense carbon dioxide (CO2) in the water. If CO2 levels get too high, fish might find it hard to breathe and swim away. So Suski wondered: “Do fish get grumpy when you expose them to CO2?”

In experiments conducted in 2010 and 2011, the Illinois researchers placed bighead and silver carp into small containers. Then the experts added varying amounts of CO2 to the water and observed the fish. At higher CO2 levels, bighead carp breathed more slowly and gulped for air at the surface. And the silver carp all passed out, rolled on their backs and floated.

In a second test, the fish got a choice. Researchers put individual silver carp into one chamber that was connected to a second. Then they began adding CO2 to the first chamber. Most fish fled into the second chamber.

The findings suggest that pumping CO2 into the water might help keep Asian carp away, says Suski. But if the gas spreads into the rest of the river, it might perturb the behavior of native fish as well. So Suski’s team is working on ways to confine the added CO2 to just one part of a river.

By learning more about Asian carp, Suski and other scientists hope to keep the fish from wreaking havoc on native animals. If carp and other invasive species spread unchecked, says Jerde, the environment that people see today “may not be the same environment they have 10 years from now.”

Power Words

algae A large group of mostly photosynthetic organisms, meaning they use light and carbon dioxide to make sugar and oxygen. Algae range from long seaweeds to single-celled microorganisms.

Asian carp Several species of fish native to Asia. Several have been introduced to many new countries, including the United States. The term covers bighead, silver, grass and black carp.

bighead carp A species of Asian carp that can weigh up to 45 kilograms (100 pounds). Bighead carp eat small organisms such as zooplankton.

carbon dioxide A gas (CO2) made of one carbon atom and two oxygen atoms.

DNA A long, spiral-shaped molecule that carries genetic information. DNA can be found inside nearly every cell of an organism.

invasive species A non-native species whose introduction may cause ecological and economic damage.

native An individual or species that grew up or evolved in a particular region of the world. Invasive species are non-native organisms and often thrive in a new region because they have escaped the natural predators that kept their numbers in check.

silver carp A species of Asian carp that usually weighs up to 27 kilograms (60 pounds). Silver carp can jump high out of the water when startled by the vibration of boat motors.

spawn To release or deposit eggs.

sperm A male reproductive cell.

zooplankton Tiny floating animals in the water that feed on single-celled plants and plantlike organisms.

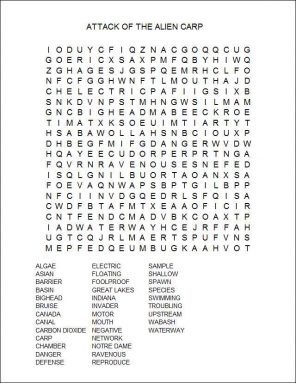

Word Find (click here to print puzzle)